Divided into two antagonistic states, Korea remains the stage for one of the longest-running conflicts of the modern era. Although active fighting ceased in the mid-20th century, the war between North and South was never formally concluded. Since then, the confrontation has merely changed form—from military to ideological. Today, artillery fire has been replaced by radio broadcasts, and spies have given way to USB drives crossing the border.

The boundary between the two Koreas is more than a fortified line of entrenched mistrust, lined with barbed wire and guard towers. Hidden among concrete bunkers and watchposts are green loudspeakers, camouflaged to look like ordinary military equipment. From these devices begins one of the most unusual and sustained information campaigns of the 21st century—a decades-long effort by South Korea to pierce the North’s isolation using culture, technology, and data as tools of influence.

One such loudspeaker near the Demilitarized Zone suddenly began broadcasting toward the North. Out came pop music, interspersed with a cheerful female voice: "Traveling abroad gives us strength." In a country where leaving the nation is considered a criminal offense, such words sound almost like provocation.

From the northern side came the sound of marches and patriotic songs—an attempt to drown out the "hostile signal." Technically, the Korean War has never ended. And while the artillery has fallen silent in recent years, the confrontation continues—in a less visible but no less intense form. This is a war of information.

Seoul is trying to break the blockade. Pyongyang is doing everything it can to preserve internal isolation. The internet in North Korea remains nonexistent. All media are under total state control.

"The reason is that much of the Kim cult is a fabrication. People are being blatantly lied to," says Martyn Williams, senior fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington and an expert on North Korean technology.

Loudspeakers along the South–North Korea border.

South Korea’s strategy rests on a simple premise: if enough myths can be dismantled, the system may begin to crumble. The loudspeakers are just the surface. The real battle unfolds in the shadows.

At night, several independent radio stations broadcast into North Korea using shortwave and medium-wave frequencies. It’s one of the few remaining ways to offer North Koreans an alternative perspective—even if it comes at great personal risk.

A flash drive donation campaign, Flashdrives for Freedom.

In parallel, thousands of flash drives and microSD cards make their way into the country each month. They’re loaded with Korean dramas, films, K-pop, and curated news compilations—everything North Korea’s state propaganda works hard to suppress.

But today, those involved in this underground mission are growing uneasy: the North is beginning to push back.

Kim Jong-un has intensified crackdowns on those distributing foreign content. More critically, funding for the entire information campaign is now at risk. Following Donald Trump’s return to the White House, many U.S.-backed aid programs have been shut down—including those that supported this covert "media front."

The decades-long information war between the two Koreas is under threat—not because of Pyongyang, but because of Washington.

Every month, staff at the South Korean nonprofit Unification Media Group (UMG) curate content—news segments, dramas, music videos—they hope will resonate with North Korean audiences. These are then loaded onto flash drives and memory cards, sorted by risk level.

"Low-risk" content typically includes popular K-dramas and K-pop hits, such as the Netflix series When Life Gives You Tangerines and tracks by Jennie, a star of the South Korean music scene. "High-risk" content is what UMG calls "educational material": information on human rights, democracy, and freedom of speech. It’s this kind of data, they believe, that Kim Jong-un fears most.

The prepared drives are sent to the China–North Korea border. There, with the help of trusted partners, they are smuggled into North Korea—often literally across the river, and often at great personal risk.

At first glance, South Korean dramas may seem like harmless entertainment. But to North Korean viewers, they reveal an entirely different world—people living in high-rises, driving luxury cars, dining in trendy restaurants. It’s a visual proof of freedom and prosperity, in stark contrast to the image of a poor, oppressed South Korea portrayed by the regime’s propaganda.

A still from the popular South Korean drama Crash Landing on You.

"Some people cry when they watch these dramas," says Lee Kwang-baek, director of UMG. "They say it’s the first time they’ve thought about their own dreams."

There are no precise figures on how many people access these flash drives. But defector testimonies confirm that the materials are spreading—and having an impact. "Most of those who have escaped in recent years admit it was foreign content that pushed them to make that decision," says Sokeel Park, a representative of Liberty in North Korea, an organization that supports the distribution of this media.

There is no organized opposition in the country. Protests are impossible. But Park hopes that at least some individuals will choose to make a personal act of defiance.

Kang Gyuri, a 24-year-old defector from North Korea, used to run a small fishing business. In the fall of 2023, she made the decision to escape—crossing the sea by boat and reaching South Korea.

The decision had been years in the making, she admits, and was largely influenced by foreign television shows. "I felt like I was suffocating. And then this intense urge to flee suddenly took over," she recalls.

We met in one of Seoul’s parks on a warm, cloudless day. Gyuri described how, as a child, she would listen to South Korean radio broadcasts with her mother. She saw her first drama at the age of ten. Later, she learned that the flash drives and memory cards carrying such content had been smuggled into the country in fruit crates.

With each new video, she says, it became increasingly clear: her reality was built on lies. "I thought it was normal—for the state to ban and control everything. I believed that’s how it was everywhere. But then I realized: it’s only like that in North Korea."

According to her, nearly everyone around her watched South Korean content. She and her friends exchanged flash drives, discussed dramas, favorite actors, and K-pop idols—especially a few members of BTS.

They also talked about South Korea’s economy. But taking those conversations any further was dangerous. "Criticizing the regime was taboo," she says.

The influence of South Korean culture showed not only in conversations but in appearance: "Young people even started to change how they dressed and spoke. North Korean youth are changing very quickly."

Kim Jong-un, officials in Seoul acknowledge, is fully aware of how deeply this undermines his authority—and he has responded with repression.

During the pandemic, Kim ordered new electric fencing to be installed along the border with China to make it harder to smuggle in flash drives and memory cards. In 2020, North Korea introduced a series of new laws imposing harsh penalties for viewing or distributing foreign content. One of them explicitly allows for the death penalty.

These measures have had a tangible effect. "In the past, you could find this kind of material openly sold at markets," recalls Lee Kwang-baek of UMG. "Now, it’s exchanged only through trusted contacts."

After the crackdown began, Kang Gyuri and her friends became much more cautious. "Now we only talk about this with people we really trust. And even then—only in whispers," she says. According to her, executions of young people caught watching South Korean content have become more frequent.

In recent months, the regime has begun targeting not only the content itself, but also behaviors associated with it. In 2023, Kim declared it a criminal offense to use South Korean slang or accents.

Across North Korean cities, so-called "youth inspection squads" now patrol the streets. Their task is to identify any deviation from state-approved behavior. Gyuri recalls how, shortly before her escape, she was repeatedly stopped and reprimanded for her K-pop–inspired hairstyle and clothing. Her phone was confiscated and her messages checked—to ensure she wasn’t using South Korean words.

In late 2024, journalists at Daily NK—a division of UMG—managed to smuggle a smartphone out of North Korea. Inside the device, they discovered an auto-replace function that instantly converted South Korean words into their North Korean equivalents—effectively deleting the "incorrect" term as it was typed. Analysts described the feature as a digital version of Newspeak.

"Smartphones in North Korea have become tools of ideological control," says Martyn Williams of the Stimson Center. In his view, after a wave of crackdowns and technological upgrades, Pyongyang is increasingly gaining the upper hand in the information war.

After Donald Trump returned to the White House in early 2025, funding was cut for a number of humanitarian organizations—including those involved in broadcasting and smuggling information into North Korea. The budgets of two U.S. Congress–funded broadcasters—Radio Free Asia and Voice of America (VOA), both of which had aired programs into the North for years—were also frozen.

Trump accused VOA of "radicalism" and "anti-presidential propaganda," while the White House said the cuts were intended to "free taxpayers from funding a radical agenda."

But according to Steve Herman, former head of VOA’s Korea bureau, the decision played straight into Pyongyang’s hands. "It was one of the few windows into the world that North Koreans had. Now it’s been slammed shut—without explanation," he says.

Unification Media Group has yet to receive an answer on whether its funding will be restored. In the meantime, Sokeel Park of Liberty in North Korea calls Washington’s actions shortsighted. "In effect—though unintentionally—Trump helped Kim," he says.

According to Park, with sanctions, diplomacy, and military pressure failing to change Pyongyang’s behavior, one tool remains effective: information. "Our goal isn’t just to contain North Korea. We want to transform it. And to do that, we have to change the nature of the state itself," he argues. "If I were an American general, I’d ask: How much does it cost? And the truth is, these are smart investments."

North Korea’s Second Economy

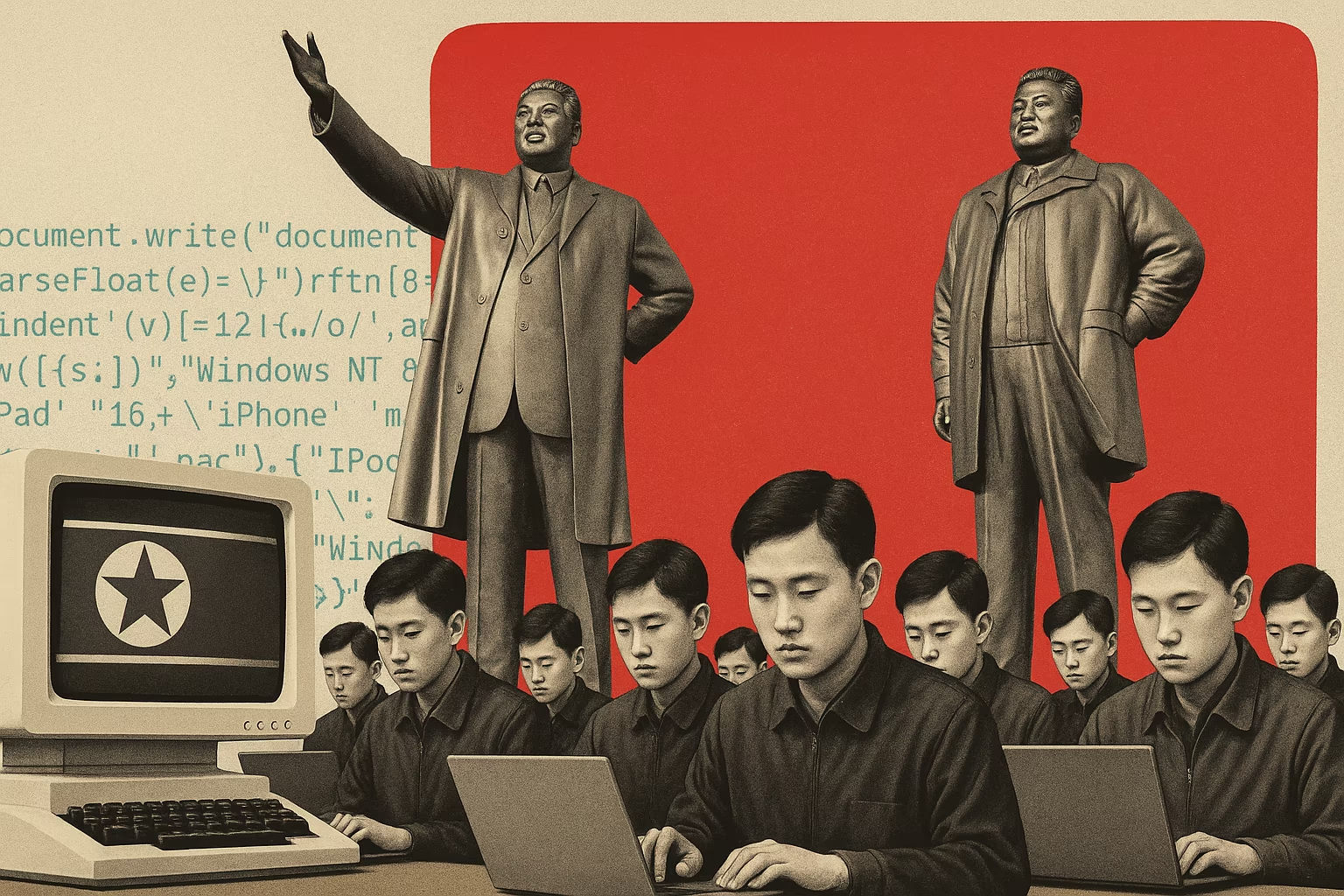

Pyongyang Has Built a System of Secretly Employing Its Programmers in the U.S., Europe, and Asia: They Earn Hard Currency, Gain Access to New Technologies, and Learn to Evade Sanctions

China Introduces Digital ID for Internet Users

The System Will Strengthen State Control Over Online Activity—and Could End Anonymity for Good

One question remains: who should pay for this war over the minds of North Koreans? Today, nearly the entire financial burden falls on the United States—and some believe that’s unfair.

A logical partner would seem to be South Korea. But within the country, anything related to North Korea remains deeply politicized. The liberal opposition has traditionally favored engagement with Pyongyang—which means open support for an "information war" doesn’t align with its platform. The frontrunner in next week’s presidential election has already stated that, if elected, he will shut down the border loudspeakers.

Still, Sokeel Park remains optimistic. "The North Korean authorities can’t remove the information from people’s minds—it’s already there, and it’s continuing to grow." And as technology advances, he believes, getting content into the country will only become easier. "I truly believe this is what will change North Korea."