Ten days into the conflict have exposed the limits of the military campaign: Israel has inflicted significant damage on Iran’s nuclear and missile infrastructure, but failed to destroy deeply buried targets. Despite its losses, Iran continues to launch strikes, maintaining residual capabilities and its status as a threat. The U.S. has not intervened directly so far, but its potential involvement could prove decisive — both militarily and diplomatically.

Ten days after the rapid onset of war, the Israel–Iran conflict has settled into a fragile equilibrium: both sides continue trading strikes, but neither is capable of landing a decisive blow — though hypothetical U.S. involvement could shift the dynamics, albeit without guaranteeing success. Iran, regardless of how the campaign unfolds, is already emerging notably weakened compared to the height of its regional influence in 2023 — though that does not mean it no longer poses a threat to Israel.

Just two years ago, Tehran believed it had built a layered system of pressure on the Jewish state. Iran-backed groups operated on Israel’s borders: Hezbollah in the north, Hamas in Gaza, and Yemen’s Houthis, capable of disrupting Red Sea shipping. Iran itself had amassed a large arsenal of medium-range missiles and was developing a "threshold" nuclear program — one that could quickly yield a bomb if needed. Tehran’s strategy relied on offensive firepower with minimal investment in air defense, assuming Israel’s air force would be deterred by the threat of retaliatory missile strikes.

That structure began to unravel after the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack. Israel, showing willingness to take major risks, proceeded to dismantle key elements of Iran’s security umbrella. Hezbollah was forced into a ceasefire and saw its influence in Lebanon wane; soon after, the regime of Bashar al-Assad collapsed, having lost support from Lebanese militants. Yemen’s Houthis also scaled back their activity after striking a deal with the U.S. Two major Iranian missile barrages in 2024 caused limited damage to Israel, while IDF air raids inflicted significant harm on Iran — including disabling much of its long-range air defense systems.

Supreme Leader of Iran Ali Khamenei and IRGC Commander Hossein Salami inspect weaponry at an exhibition in Tehran.

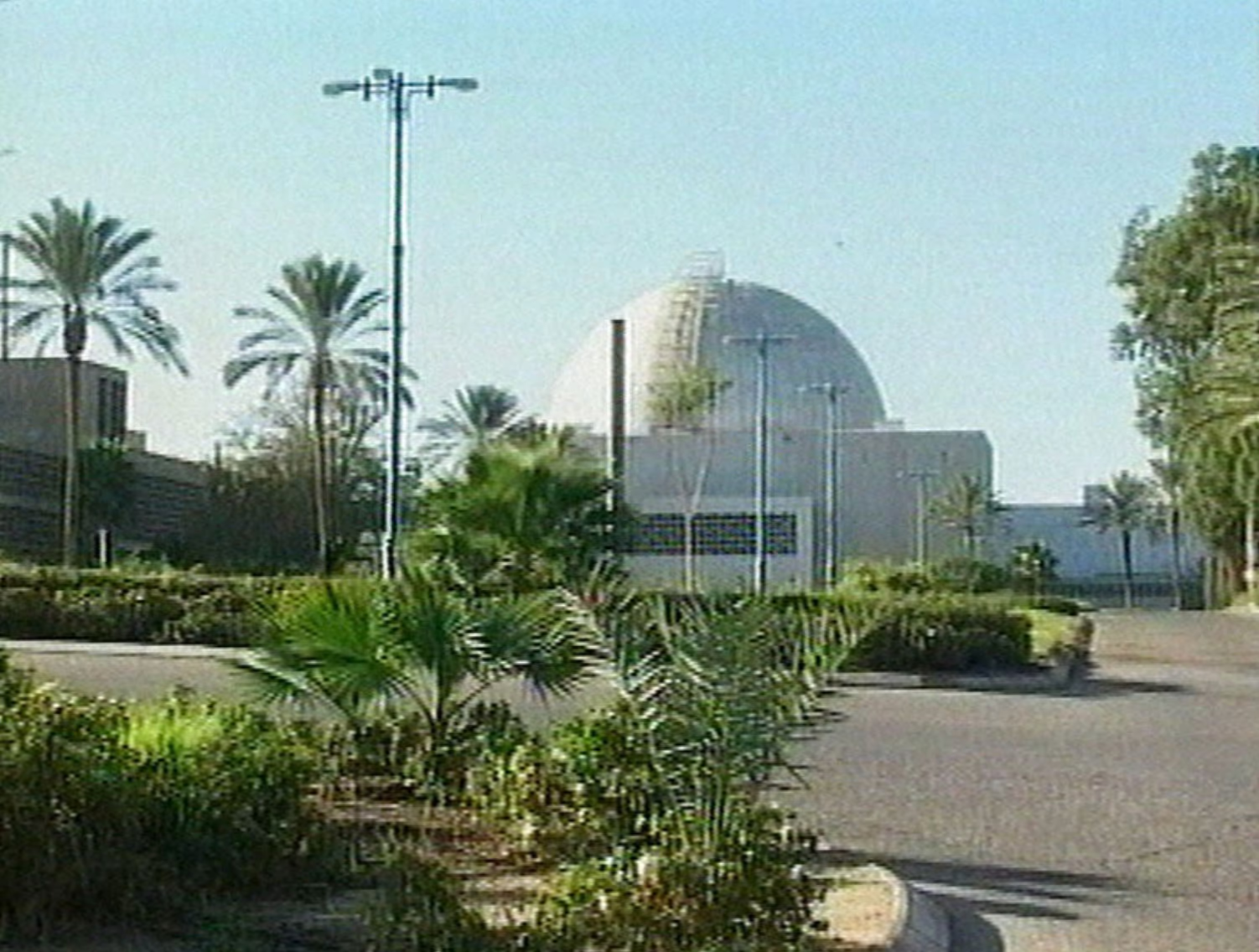

After gaining operational advantage, Israel launched an air campaign and covert operations, officially declaring its goal to be the destruction of Iran's nuclear and missile infrastructure. Within the first week, Israeli forces disabled the above-ground pilot facility in Natanz, damaged power substations and gas centrifuges, struck processing plants in Isfahan, effectively shut down the heavy-water reactor in Arak, and destroyed centrifuge production sites. Only the deep-underground facilities—primarily Fordow near Qom and the new underground complex in Natanz—survived, protected by depths unreachable by conventional munitions.

Prior to the strikes, Iran had about 500 kg of uranium enriched to 60%, with a monthly growth rate of 37 kg. Considering early-2000s research and the "Amad Plan archives" discovered in 2018, most bomb components are either ready or can be rapidly produced. However, a functioning warhead requires weapons-grade uranium (≈90%), and Iran may no longer possess the key capability to convert UF₆ gas into metallic uranium.

U.S. involvement could prevent Iran from solving this problem. Only Washington possesses enough GBU-57 bunker-busters capable of penetrating to such depths—though even these may not be sufficient to destroy Fordow, protected by 80–90 meters of rock and reinforced concrete. The White House remains hesitant: striking a formally civilian facility without IAEA mandate and risking entanglement in a new war runs counter to the administration’s preference for a diplomatic "capitulation" by Tehran.

Rocket trails in the sky over Nuseirat in central Gaza on the evening of June 13, 2025—after Iran launched strikes on Israel in response to a massive assault on its nuclear and military facilities.

Despite losing several underground facilities and some mobile launchers, Iran’s missile forces can still fire dozens of rockets per day. Pre-war estimates put the arsenal at 2,000–3,000 ballistic missiles; even with daily expenditures in the dozens, reserves could last for months. Israel, in turn, faces limits on its missile defense: Arrow batteries are depleting interceptors, while resupply depends on U.S. assistance and the deployment of THAAD systems. As a result, the attritional war between Iranian missiles and Israeli defenses remains unresolved.

The economic and military costs for Iran are rapidly mounting. Missile strikes have failed to inflict decisive damage on Israel; infrastructure is being destroyed, oil exports disrupted, and proxy networks weakened. Eventually, the regime may face a choice: enter negotiations to sharply limit its missile and nuclear programs or risk direct U.S. intervention. Relying on the “threshold” status Tehran maintained for two decades is no longer viable—its deterrence strategy has been effectively dismantled.

For Israel, even a weakened but unbroken Iran remains an existential threat, especially if it retains the capacity for rapid bomb assembly. Talks under international supervision—resembling the 2015 JCPOA, with long-term, verifiable constraints and IAEA inspections—could prove more reliable in the long run than the partial destruction of infrastructure Iran may eventually rebuild. But for that scenario to emerge, the clerical regime must first survive and preserve at least a minimal missile capability. Without it, unconditional surrender may become the only path.

No More Proxies

Trump Has Done What He Promised to Avoid

The Strike on Iran Turns a Pressure Strategy Into an Unpredictable Gamble

Fordow Is Iran’s Underground Nuclear Facility, Out of Reach for Israeli Strikes

Here Is What We Know About It

Israel Strikes Iran, Accusing It of Seeking Nuclear Weapons

Yet Israel Itself Has Long Possessed Them—Though Never Officially Admitted

Netanyahu Ignores Trump’s Warnings and Launches Operation Against Iran