Since October 2023, international media attention has focused squarely on the Gaza Strip—under blockade, airstrikes, and facing a humanitarian catastrophe. Yet beyond the headlines, a no less significant and far-reaching process is unfolding in the West Bank. In the shadow of the war, the Israeli government is systematically reshaping the legal and administrative regime of the territory—accelerating settlement expansion and displacing the Palestinian population. This is no longer the result of isolated initiatives, but a coordinated state strategy encompassing land, infrastructure, law, and demographics.

Since 1967, following its victory in the Six-Day War, Israel has maintained control over the West Bank. The United Nations considers the territory occupied, but Israel avoids using that term—primarily because international law imposes strict limitations on occupying powers, including a ban on transferring their own population into occupied areas. In Israel’s official narrative, the West Bank is not "occupied" but rather a "disputed territory."

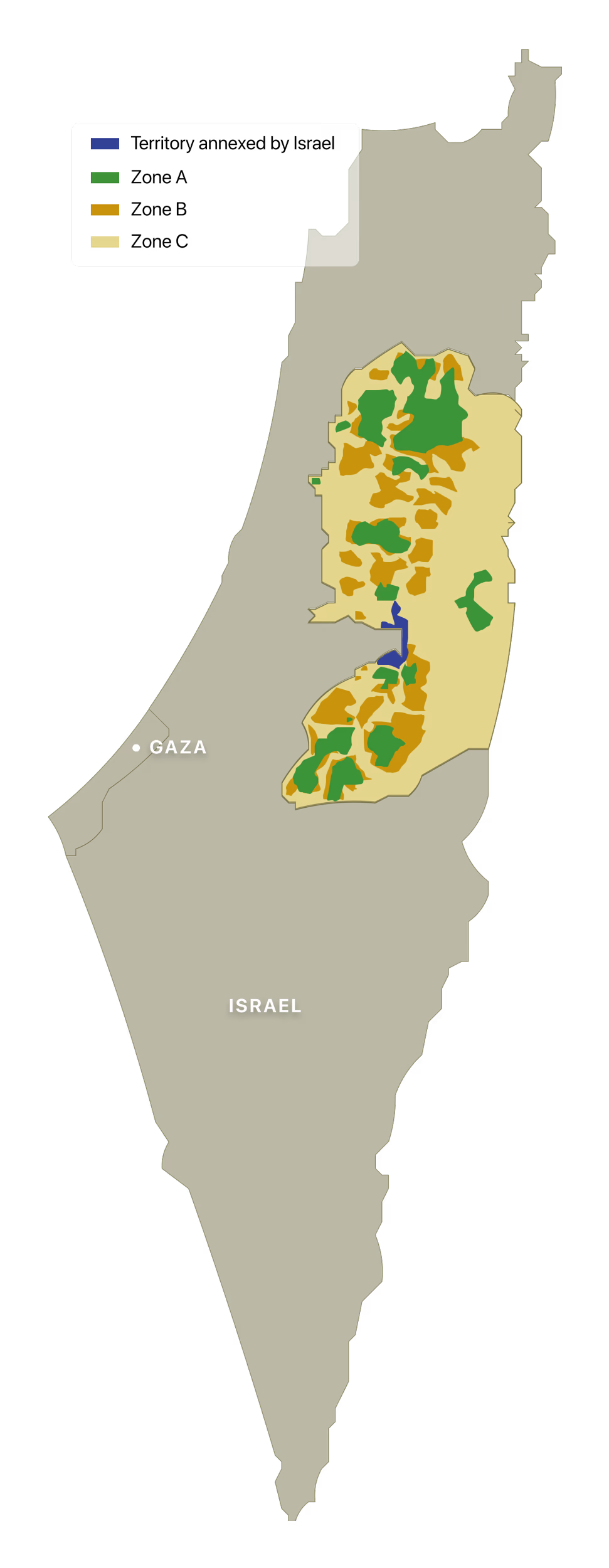

The West Bank has been claimed since 1988 by the partially recognized State of Palestine, declared by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Israel does not recognize its sovereignty. Under the 1993 Oslo Accords, signed by Israel and the PLO, the territory was divided into three administrative zones: Area A is under full control of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA); Area B is under Israeli military and Palestinian civil control; and Area C is fully governed by Israel, both militarily and administratively.

Area C covers roughly 60% of the entire West Bank and includes most of its undeveloped and agricultural land. Civil administration in this zone is overseen by a unit within Israel’s Ministry of Defense. It is on this land that Israeli settlements are concentrated—ranging from small kibbutzim to large urban clusters—built beyond the internationally recognized borders of Israel.

Status of West Bank Territories According to the Oslo Accords

Israeli soldiers detain a resident of the Nur Shams Palestinian refugee camp near Tulkarm.

The settlement movement—a network of political parties, foundations, and civil society groups advocating for Jewish settlers—has long been a powerful force in Israeli domestic politics. Its ultimate goal is the annexation of the entire West Bank, but without granting the Arab population the right to self-determination. Radical factions call for the forcible removal of Palestinians, while more moderate voices advocate encouraging emigration.

Today, the movement is experiencing an unprecedented surge—backed actively by the state. On May 13, 2025, the Israeli government approved a new land registration system for Area C: from now on, Israel will no longer recognize any land rights issued through the Palestinian Authority. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who spearheaded the move, described it as part of the "sovereignty revolution" Israel is carrying out in the West Bank.

Bezalel Smotrich is one of the central figures behind what many describe as the most right-wing cabinet in Israel’s history. Leader of the Religious Zionism party, finance minister, and also a minister within the Ministry of Defense (though not the defense minister himself), he plays a key role in West Bank governance. Smotrich lives in the settlement of Kedumim near Nablus—embodying the fusion of state authority and the settlement enterprise.

His political agenda is focused on accelerating what he calls the "establishment of full sovereignty" over the West Bank. In practice, this amounts to steps toward de facto annexation—without the need for formal declaration. According to Smotrich, the strategy rests on demographic pressure. Currently, about half a million Israeli settlers live in the West Bank. The goal is to raise that number to 1.5 million, making Jews the majority. At the same time, the strategy includes the displacement of part of the Arab population—through economic or political means, or by incentivizing emigration.

This strategy is being implemented on multiple fronts. On May 13, 2025, the cabinet approved a change in property registration procedures in Area C: Israel will no longer recognize land rights issued by the Palestinian Authority. The initiative was framed as part of the "sovereignty revolution."

At the same time, the Knesset is advancing a bill titled "On the Elimination of Discrimination in Land Purchases in Judea and Samaria." Drafted by Smotrich’s party, the bill aims to repeal a 1953 Jordanian law that prohibits foreigners from purchasing land in the West Bank. At the time, "foreigners" primarily referred to Jews. While the law never prevented settlement construction—thanks to legal workarounds available to Israel’s Ministry of Defense—it has long been viewed by settlers as a legal anomaly. The proposed legislation seeks to eliminate it both symbolically and practically.

Despite its sensitivity, the bill has faced little resistance: the military, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Justice, and members of both the coalition and the opposition have not opposed it. This reflects a broader shift in the political mainstream—toward normalizing and accelerating the expansion of settlements.

In addition to Smotrich, the settlement agenda is also being advanced by Minister for Settlement Affairs Orit Strock, another member of the Religious Zionism party. Administrative authority, budgetary resources, and legislative initiatives are all being used as tools to gradually entrench Israeli control over territory that the majority of the international community still considers occupied.

Bezalel Smotrich.

Not long ago, Bezalel Smotrich’s plan for the "creeping annexation" of the West Bank was seen as a political fantasy. Even after he entered government in late 2022 and began promoting his agenda within the limits of his official powers, few expected any real progress: his initiatives were largely viewed as routine ideological signaling, destined to be stalled in parliamentary committees.

That was the case, for example, in the summer of 2023, when Smotrich’s allies introduced a bill to allow Jews to purchase land in the West Bank. Moderate politicians, as usual, warned that violating the status quo would only inflame tensions, and it seemed the proposal would again be buried in protracted hearings and postponed votes.

But on October 7, 2023, Hamas launched the largest assault on Israel in the country’s history. The war that followed reset the bounds of what was politically acceptable. Much of what had once been dismissed as radical became mainstream. Talk of "sovereignty," "demographic control," and "irreversible steps" in the West Bank no longer triggered immediate pushback.

Throughout the fighting—up until the ceasefire in January 2025—one of the Israeli military’s central concerns was the outbreak of a second front in the West Bank. That uprising did occur, but on a limited scale. In the northern city of Jenin, the "Jenin Brigades"—a militant coalition including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and other extremist groups—rose up. The Palestinian Authority attempted to quell the unrest with its own forces but failed to bring the situation under control. The conflict was contained, but not resolved.

On January 21, 2025, less than a week after the Gaza ceasefire, the Israel Defense Forces entered Jenin. The rebellion was crushed by force. According to reporting by The New York Times, citing Palestinian sources, nearly 40,000 people in Jenin and nearby Tulkarm lost their homes in less than a month. The campaign is ongoing: the Israeli army continues to carry out forced evictions and demolitions of entire neighborhoods under the pretext of securing areas that may harbor militants.

The Israeli military has not commented on the extent of the destruction. But according to left-leaning outlets—ranging from the moderate Haaretz to the radical +972 Magazine—the cities have not witnessed destruction on this scale since the start of the Second Intifada.

Tulkarm.

The Israeli military has grounds to claim that the northern West Bank remains a hub of militant activity. On May 14, gunmen opened fire on a car near the settlement of Peduel. The victim was 30-year-old Tze’ela Gez, who was on her way to the maternity ward. Her husband was injured. Doctors performed an emergency C-section—their newborn, the couple’s fourth child, remains in intensive care.

The next day, Israeli forces raided a house in the Palestinian town of Tamun, killing five members of Islamic Jihad and arresting another. They were reportedly believed to be connected to the attack on the Gez family. On May 17, the army arrested several Palestinians and shot another, officially declaring them suspects in the case.

This cycle of violence—an attack, a raid, another attack—has long defined the West Bank. The Israeli army frames its actions as retaliation for terror, while Palestinian groups portray their operations as responses to Israeli raids.

Israel has for decades maintained a policy of demolishing the homes of terrorists, and the house in Tamun is likely to be destroyed. But what is happening in Jenin and Tulkarm goes far beyond that tactic. Entire neighborhoods are being emptied. Local residents say the situation is worse than during the Second Intifada (2000–2005), when Israeli military operations were harsh but more targeted.

Northern West Bank is home to several Palestinian refugee camps with a combined population of around 40,000. Though these areas now function as urban districts, their "refugee" status remains central to residents’ political and personal identity. As such, widespread destruction in these zones is seen not only as a tactical move, but as an attempt to erase the symbolic presence of Palestinians. One source in Tulkarm told The New York Times outright that Israel’s goal is "to push the refugees from the north to the center of the West Bank and wipe the camps off the map."

As military operations and demographic pressure escalate, legislative measures are advancing in parallel. On January 29, the long-stalled bill allowing Jews to purchase land in the West Bank made progress in the Knesset. Other initiatives are also being considered: integrating settlements into the national gas network, transferring archaeological sites to the Israeli Antiquities Authority, and other measures aimed at the legal and infrastructural incorporation of the West Bank.

A symbolic marker of this policy came on May 13, when excavations began near Nablus—at the site of ancient Samaria (Shomron), capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel in the 10th–7th centuries BCE. Minister of National Heritage Amichai Eliyahu (Jewish Power party) and Samaria Regional Council head Yossi Dagan made no secret of their motives: the digs are intended not only as a scientific endeavor but also a political one. Their goal, they said, is to "strengthen the Jewish people’s connection to their land"—in other words, to legitimize Israeli claims not just through security, but through history.

Since the start of the 2023 war, the settler movement in the West Bank has grown significantly more assertive. At sectoral conferences, its leaders increasingly speak of the need to "create demographic facts on the ground"—that is, to sharply increase the share of Jewish residents—and to pursue an administrative restructuring of the region. These events are attended not only by ideological figures, but also by serving ministers, including Bezalel Smotrich.

Nur Shams Palestinian refugee camp near Tulkarm.

Such forums were held in the past as well, but they were largely perceived as ideological rituals rather than actionable roadmaps. That has now changed: many of the once-symbolic political declarations are being implemented—with the involvement of state institutions and the Israel Defense Forces, which is especially significant given the unique legal regime in place in the West Bank.

How far this process will go remains uncertain. The current government's mandate runs through October 2026, when the next Knesset elections are scheduled. However, some experts believe the coalition could collapse earlier: internal tensions among its members are already creating pressure that could lead to snap elections.

Smotrich’s party—Religious Zionism—risks losing its parliamentary representation. Even if it manages to retain a few seats, it is unlikely to be invited into another governing coalition. Still, a major reversal in Israeli policy toward the West Bank seems improbable.

The most likely candidate for prime minister in the event of a power shift is Naftali Bennett, a conservative and nationalist who previously held the post. He too supports West Bank annexation, albeit in a more pragmatic form. So while the pace of the "sovereignty revolution" may slow, the political momentum set in motion by the current administration is likely to endure.

Might Over Right

Israeli Forces Open Fire Again Near Aid Points—Dozens Killed

Israel Insists on Controlling the Relief System, Pushing Out the UN and NGOs

Israeli Strike on Gaza School Kills 33—Army Says Militants Were Hiding in the Building

Israel Launches Airstrike on Jabalia

At Least 48 Dead, Including 22 Children

Israel Keeps Gaza Under Total Blockade, Cutting Two Million People Off From Food, Water, and Medicine

This Is Not a Humanitarian Crisis—It’s a Deliberate Siege

Blockade and Economic Devastation Leave Gaza Without Food

Families Survive on Canned Goods and Aid