Following a terrorist attack in Kashmir, Indian authorities launched a sweeping campaign against alleged undocumented migrants from Bangladesh. Under the pretext of addressing national security threats, Muslims who speak Bengali are being detained and deported—including residents born and raised in India. Human rights groups say the policy is arbitrary and deepens discrimination.

A waste collector from the slums of Delhi said he was deported along with his pregnant wife and son. A rice farmer from Assam, in India’s northeast, reported that his mother spent several weeks in police custody. A 60-year-old caretaker of a shrine in Gujarat said police blindfolded and beat him before putting him on a boat.

All of them were caught up in the government’s broad anti-migrant drive, which Indian authorities justify on national security grounds. According to rights advocates, the campaign—intensified after the April attack in Kashmir—is increasingly arbitrary, aimed at intimidating Muslims, especially those whose language marks them as “outsiders.” Most detainees live hundreds of miles from Pakistan, which India blames for the assault.

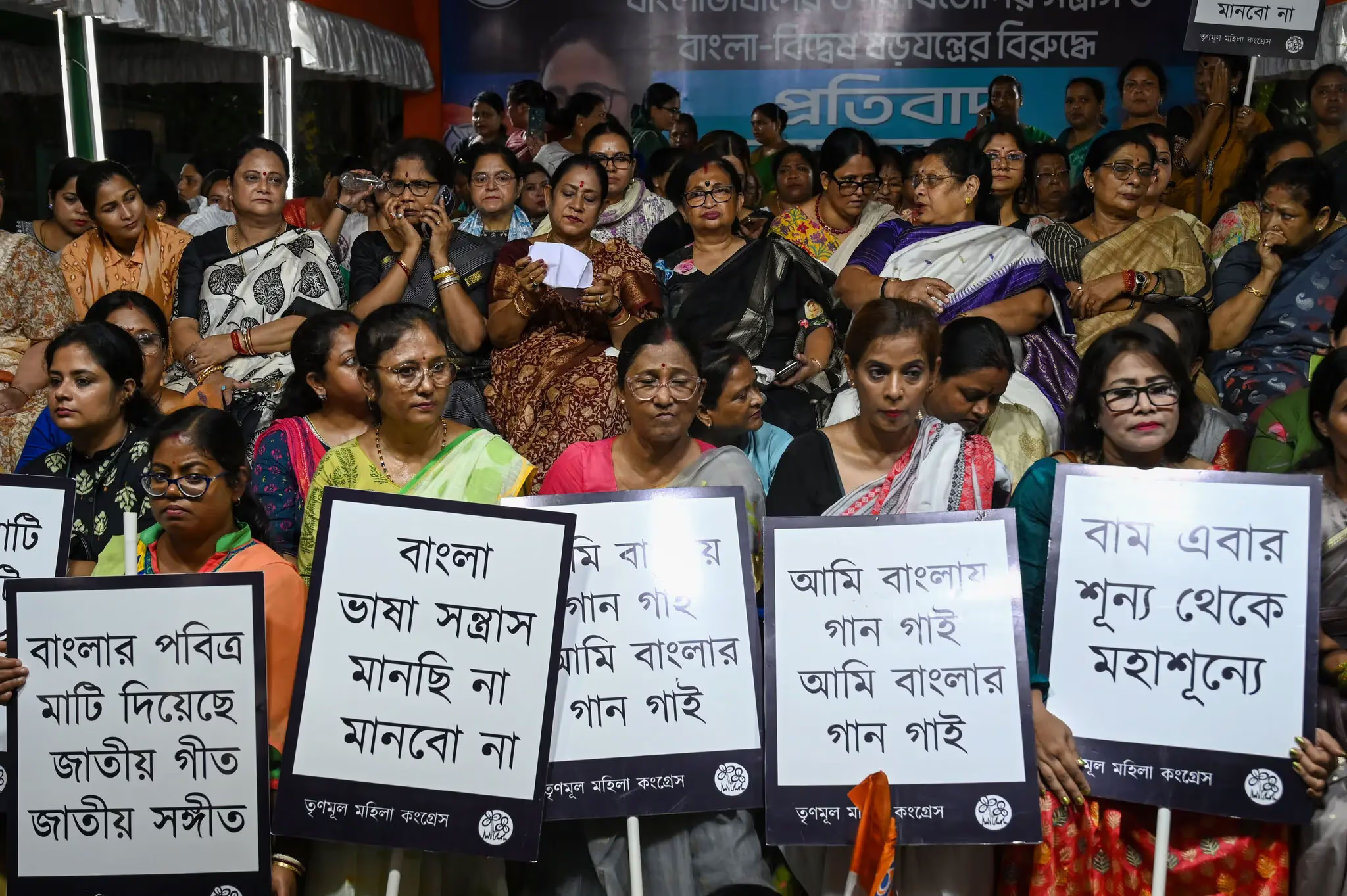

Thousands of Bengali-speaking Indians, most of them Muslim, have been detained, placed in holding centers, or deported to Bangladesh. Many come from West Bengal, where Bengali is the dominant language. For decades, young people from the state have moved to major Indian cities in search of work.

India is believed to host several million undocumented migrants from Bangladesh, who have crossed—legally or illegally—the open and lightly monitored border between the two countries. In a number of Indian states, raids have been carried out in areas with a high concentration of Bengali speakers, ostensibly on the basis of intelligence about undocumented residents. Bengali is an official language in both India and Bangladesh, spoken by tens of millions on either side of the border.

A residential block in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, demolished in April. Local authorities claimed it had been illegally occupied by migrants from Bangladesh.

Avjit Paul, an 18-year-old Hindu, said he moved from his native West Bengal to Gurgaon to work as a cleaner. He recounted that during a police raid on the slum where he lived, he was detained for five days despite showing officers a government-issued ID card. He was released only after social workers provided additional documents proving his Indian citizenship. Millions of Indians lack papers that can definitively confirm their nationality.

Fearing another arrest, Paul left Gurgaon and returned to West Bengal. “I’m afraid of being in that situation again just because I speak Bengali,” he said, adding that he is now unemployed.

India and Pakistan

The War That Never Ended

How the Conflict Over Kashmir Became a Fixture of India and Pakistan’s Politics—and Why It Still Can’t Be Stopped?

A New Threshold of Threat

How Technology, Ideology, and Diplomatic Inaction Reshaped the India–Pakistan Conflict

Human rights advocates and lawyers have criticized the government’s migration campaign for lacking proper legal safeguards. They say the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is using the April attack as a pretext to intensify systematic pressure on the country’s Muslim population.

In BJP-governed states, thousands of alleged Rohingya Muslims or migrants from Bangladesh have been detained since the attack. Police figures show at least 6 500 arrests in Gujarat, 2 000 in Kashmir, and about 250 in Rajasthan. In May, Rajasthan authorities opened three new detention centers. However, according to lawyer Supanta Sinha, who represents detainees, the actual number in that state is closer to a thousand.

No precise data exist on the number of people deported from India to Bangladesh. Bangladeshi officials say around 2 000 people were expelled from India between May and July, but Indian authorities have not confirmed that figure.

Security forces patrol the India–Bangladesh border in Assam. May 2025.

According to a report published by Human Rights Watch in July, Indian authorities have had to bring back several dozen people who were able to prove their citizenship after being deported across the border. As noted by Meenakshi Ganguly, HRW’s deputy Asia director, the campaign primarily targets Muslim migrants from the poorest segments of society.

Twenty-one-year-old Amer Sheikh left West Bengal to work in construction in the western state of Rajasthan. According to his uncle, Ajmaul Sheikh, police detained him in June despite his having a government-issued ID card and a birth certificate. After three days in custody, all contact with him was lost.

In late June, police arrested 27-year-old waste collector Danish Sheikh, a native of West Bengal, along with his pregnant wife and eight-year-old son. Sheikh said that after five days in detention they were deported, dropped in the jungle, and told to walk toward Bangladesh. The family has remained there since, despite decades-old Indian land ownership papers and national ID cards. “We don’t know when we will be able to return home,” said Sheikh’s wife, Sunali Khatun.

Sixty-year-old Imran Hossein recounted that after a police raid in his neighborhood in Gujarat, he was blindfolded, beaten, and taken by boat to Bangladesh over five days. He now suffers from insomnia. “When I try to sleep, I can still hear people screaming,” Hossein said.

Leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), at both national and regional levels, have for years described the situation as a crisis of “infiltration” from Bangladesh, which they say threatens India’s identity. They focus particular attention on border states such as Assam. In July, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma wrote on X warning of an “alarming demographic shift” and pledging that his state would “fearlessly resist the ongoing and unchecked Muslim infiltration across the border.”

In Assam, Muslims make up about one-third of the population, and the question of Bengali-speaking residents’ identity has been a source of tension for decades. During the latest deportation drive, Sarma invoked a 1950 law that allows the state to expel suspected undocumented immigrants while bypassing existing tribunals.

“This is truly frightening,” said lawyer Mohsin Bhat, who has studied citizenship-related court cases in Assam.

Рисовод Малек Остер из Ассама последние недели пытается выяснить, как добиться освобождения своей матери, которую, по его словам, полиция забрала в начале июня. Где она находится, правоохранительные органы ему не сообщают.

«У моей матери есть избирательная карточка, карта Aadhaar и продовольственная карточка, но полиция их не признала, и мы не знаем почему», — говорит он. Остер подчеркивает, что его семья никогда не была в Бангладеш. Но, как и многие говорящие на бенгали в Индии, он все больше ощущает себя чужим. «Из-за этой кампании я боюсь говорить на бенгали, когда выхожу из дома», — признается он.