This question is increasingly central to debates about the future of work and closely tied to the growing interest in the four-day workweek. According to Convictional CEO Roger Kirkness, his team was able to shift to a 32-hour schedule without any pay cuts—thanks to AI. As he told his staff, "Fridays are now considered days off." The reaction was enthusiastic. "Oh my God, I was so happy," said engineer Nick Wechner, who noted how much more quickly he could work using AI tools.

The issue is also being raised at a higher level. Senator Bernie Sanders recently brought it up on Joe Rogan’s podcast: "You’re a worker, and your productivity is increasing because of AI. Instead of throwing you out on the street, I’m going to reduce your workweek to 32 hours." Sanders has already introduced a bill proposing a four-day workweek, though it stands little chance in the current Congress.

AI Profile

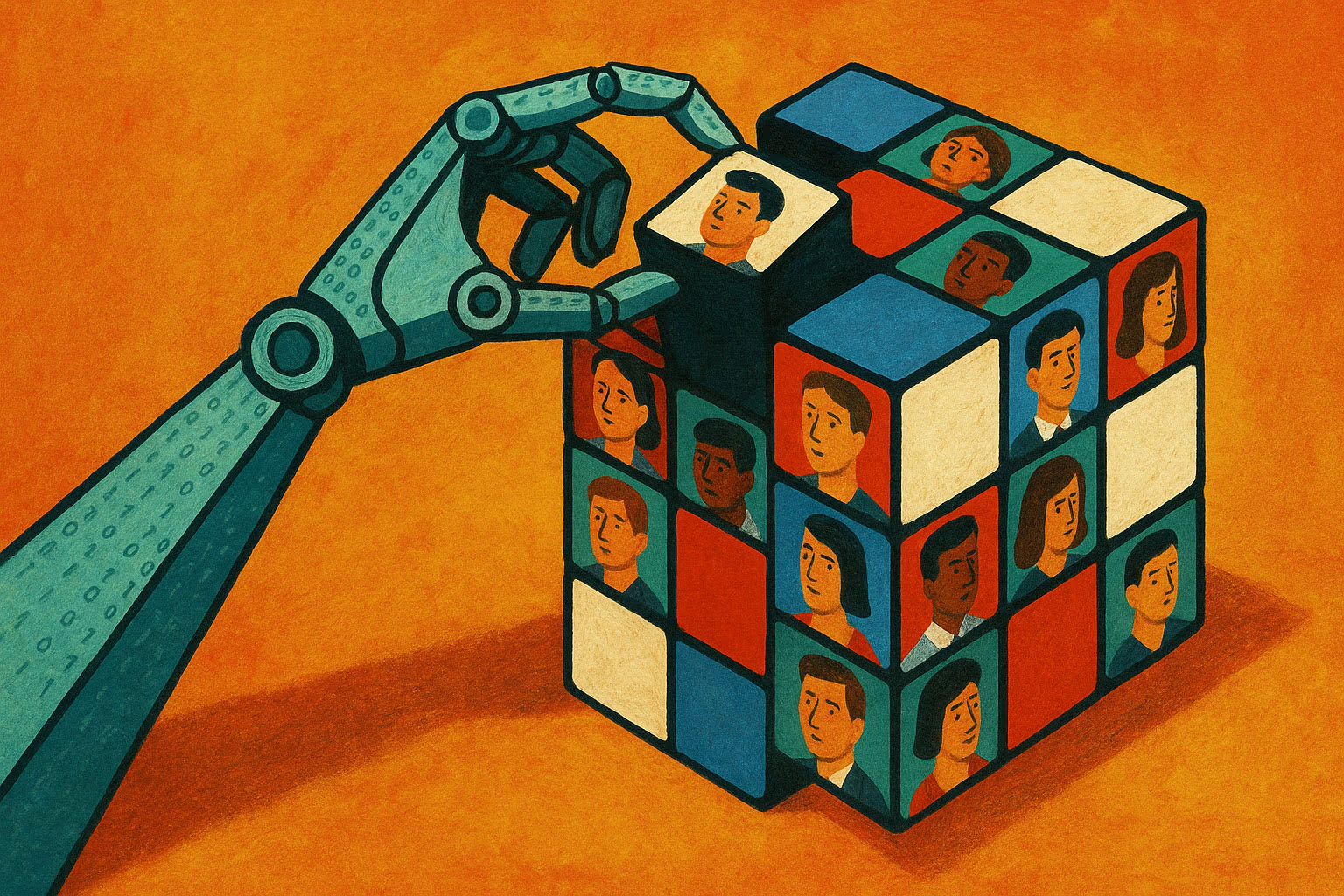

Managers Now Supervise Twice as Many Employees as Five Years Ago

Companies Are Cutting Middle Management and Offloading Tasks to AI and Remaining Staff

Managers Are Increasingly Relying on AI for Firings, Promotions, and Bonuses

Algorithms Are Shaping Employees’ Lives Despite Lacking Training and Oversight

Companies Introduce AI With the Threat of Layoffs

But That Strategy Risks Undermining Trust and Demotivating Staff

AI and the Layoff Myth

Despite Fears, Generative Artificial Intelligence Has Yet to Displace Workers—In the U.S. or Other Advanced Economies

The idea isn’t to cut jobs, but to share the gains from new technologies—giving workers some of their time back. This not only eases fears about automation but also encourages people to use AI productively. According to economist Juliet Schor, author of Four Days a Week and lead researcher for the international 4DWG project, AI has become a central topic of discussion among supporters of shorter working hours: "If large language models like ChatGPT can replace millions of well-paying jobs, we need to plan ahead. Reducing working hours is a powerful way to preserve employment."

Implementation depends on the scale of the business. Experts say small companies find it easier to adopt a four-day week, while large firms are more likely to opt for layoffs to satisfy investors. But the concept itself is not new. In the early 20th century, the argument for reducing unemployment helped push through the five-day workweek—something that was once seen as a radical innovation.

AI does accelerate routine tasks like writing code, Kirkness notes, but complex problems still require thinking, creativity, and a deep understanding of the customer. His approach: fewer hours, more intentionality. "The only things that will matter in the future of work are creativity, human judgment, emotional intelligence, the ability to formulate good prompts, and deep knowledge of the customer domain," he wrote in a message to employees. "And none of those skills depend on how many hours you work."

The same idea—less hustle, more depth—is championed by Cal Newport, author of Slow Productivity. His concept centers not on speeding up, but on slowing down with purpose. And the broader message is increasingly framed as a matter of fairness: technology should serve people, not the other way around.

AI Profile

Ideology at the Top, Infrastructure at the Bottom

While Washington Talks About AI’s Bright Future, Its Builders Demand Power, Land, and Privileges Right Now

Can Apple Catch Up With the AI Boom It Helped Trigger?

As Google Rolls Out Integration, Cupertino Still Lags Behind on Core Features