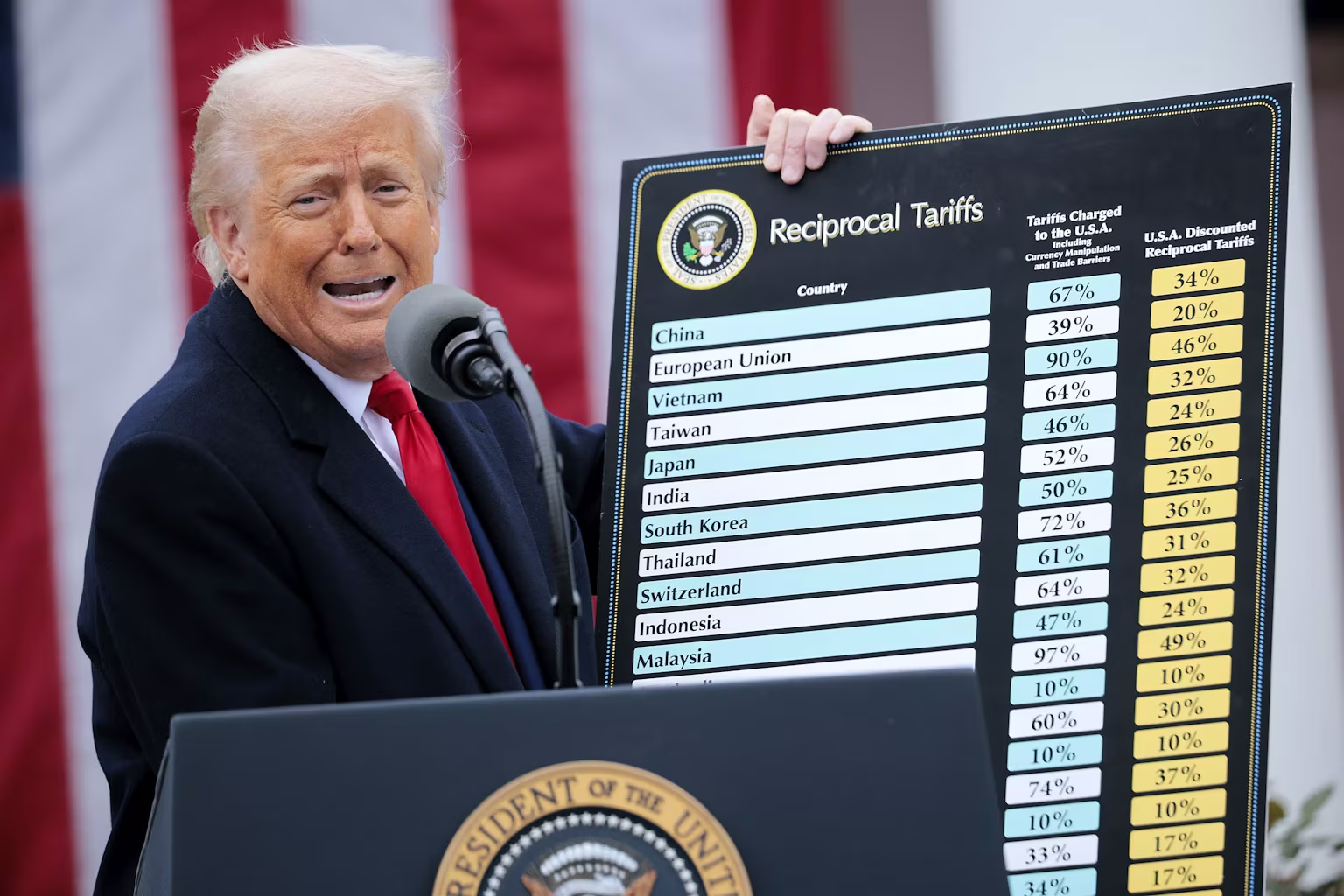

On April 2, speaking in the White House Rose Garden, Trump announced a 10% tariff on all imported goods, as well as higher "reciprocal" tariffs for countries that, in his view, have treated America unfairly. These measures mark a return to the protectionist trade policies of the late 19th century.

To the surprise of many, Donald Trump, upon returning to the White House, went significantly further than even the boldest analysts had predicted. In just ten weeks, he erected a sweeping protectionist barrier around the American economy, marking a sharp shift in the country’s economic direction. This new wave of tariff policy has sparked concern both within the U.S. and abroad. Critics warn that such measures could trigger a chain reaction of retaliatory moves from trade partners and escalate tensions in the global economy.

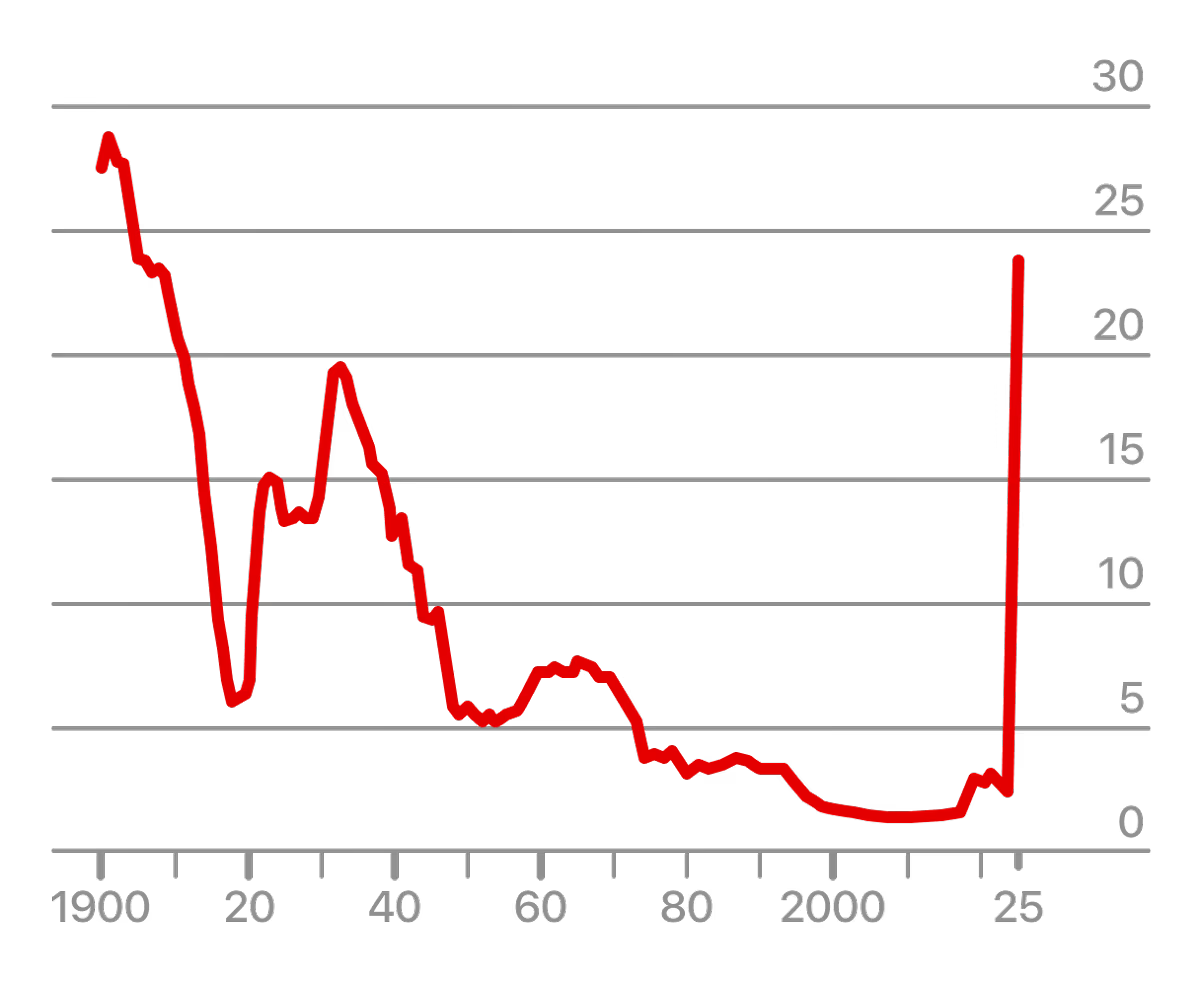

Effective U.S. Tariff Rate, %

For Trump himself, the imposed restrictions are not merely a political gesture, but an attempt to put an end to the era of increasingly free global trade. In his view, open markets allowed other countries to benefit from America’s generosity for years. "For many years, hardworking Americans were forced to stand by while other countries grew richer and more powerful—often at our expense… Now it’s our turn to prosper," he declared. The announced tariffs—unprecedented in scale even compared to Trump’s first term—were described by him as a "declaration of economic independence."

"From 1789 to 1913 we were a tariff-backed nation, and the United States was proportionately the wealthiest it has ever been, [...] we were collecting so much money, so fast, we didn’t know what to do with it. Then, in 1913 for reasons unknown to mankind, they established the income tax so citizens, rather than foreign countries, would start paying the money necessary to run our government. Then in 1928 it all came to a very abrupt end with the Great Depression, and it would have never happened if they had stayed with the tariff policy; it would have been a much different story. They tried to bring back tariffs to save our country, but it was gone. It was gone. It was too late, nothing could have been done."

Donald Trump, April 2, 2025

Donald Trump, April 2, 2025

At the same time, the president conveniently sidesteps two key points: it was globalization that brought the United States unprecedented economic growth, and the U.S. itself was the chief architect of the international trade system. Now, if Trump’s plans are fully implemented, it would amount to a complete dismantling of the economic order built after World War II. In its place, he appeals to the past—to the late 19th century, when, in his view, America thrived, despite the fact that the country was objectively much poorer at the time. "We can be so much richer than any other country that it’s hard to even believe," he declared.

Meanwhile, business leaders, investors, and diplomats are scrambling to make sense of the new tariffs, and with each passing day, it becomes increasingly clear: the scale of the changes exceeds even the most pessimistic forecasts. According to analysts at Evercore ISI, the average weighted import tariff rate in the U.S. will now reach nearly 24%—a sharp increase from around 2% just a year ago.

Both Americans and the rest of the world have very little time to adapt: the universal 10% tariff on imports from all countries is set to take effect on April 5. And on April 9, the so-called "mirror" tariffs will come into force—measures targeting countries with large trade surpluses in their dealings with the U.S.

According to the White House, the calculation of these rates factored in not only retaliatory tariffs imposed by other countries but also parameters such as currency manipulation and trade barriers. The administration emphasizes that the final rates were "generously" reduced by about half—"an act of great generosity," as the president put it. However, available data suggest that much simpler calculations were used in practice: most likely, the rates were determined based on the ratio of the U.S. trade deficit with a given country to its export volume.

The results of this method are striking: the European Union will face tariffs of 20%, India—26%, Vietnam—46%. China is expected to see at least 54%, as the "mirror" rate will be applied on top of existing duties.

An additional blow was dealt to cross-border e-commerce: Trump announced plans to eliminate the loophole that allowed goods worth up to $800 to be imported into the U.S. duty-free. This will especially hit Chinese manufacturers.

However, certain exemptions have been provided. Some sectors—including the automotive industry—will be subject to tariffs separately from country-based rates. This means, for example, that cars from Germany will face only the new 25% auto tariff, without the additional general EU rate. The same logic will apply to imports of aluminum and steel. An exception has also been made for goods from Canada and Mexico—two key U.S. partners. If products meet the requirements of the USMCA, they will be exempt from the new tariffs. Otherwise, they will face a 25% duty.

Beyond that, the list of exceptions is essentially exhausted. "If you want your product to be tariff-free, make it right here in America," Trump emphasized.

Until recently, experts believed that tariffs were more of a bargaining tool for Trump than an end goal. Some argued he used them to extract concessions from other countries, while others thought he was held back by the stock market, to which he paid close attention. However, the wave of new restrictions—and especially the April 2 announcement—has thoroughly dispelled those theories.

Referring to a televised interview from forty years ago, the president explained that he has always been skeptical of free trade, believing that other countries profit at America’s expense. He emphasized that he does not blame foreign leaders—in his view, they are simply acting in the interests of their own countries. The real fault, he said, lies with previous U.S. presidents. As for the stock market, Trump downplayed its importance, saying that true success means restoring American industrial production.

This stance raises serious questions for the economy. The S&P 500 index, which includes the country’s largest companies, has already fallen nearly 10% from its record high in late February. On the eve of the tariff announcement, the market showed signs of stabilizing, but following Trump’s evening address, futures dropped sharply—signaling a likely major decline on April 3. Global markets also face the risk of widespread selloffs.

The negative impact on economic growth is likely to be much more severe than expected. Even before the new tariffs took effect, consumer sentiment was deteriorating, and business uncertainty was rapidly rising. Most economists had hoped that domestic momentum would help avoid a deep downturn, but that confidence may have been premature. According to Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s, a recession will become inevitable if the measures are fully implemented.

It appears short-term losses are a price Trump is willing to pay to achieve his goals. He claims the tariffs will help restore industry and bring in "trillions and trillions of dollars" to the treasury—supposedly allowing for tax cuts and reductions to the national debt. Economists call such projections wildly unrealistic, pointing out that the impact of a massive, long-term tariff wall protecting inefficient industries would outweigh any potential benefits. But Trump seems convinced he has exposed the illusion of global trade. "Now we must start taking care of our own country," he declared. In his view, America—despite its economic and political dominance—remains a victim that must now defend its own interests.

Trump-Pump-Pump

The U.S. Is Losing Investor Confidence—But the Dollar Remains Irreplaceable

Trump’s Policies Undermine the Foundations of the Global Financial Order, Yet the Dollar Still Has No Real Rivals

Politics of Loud Threats

Ultimatums as Donald Trump’s State Strategy

Who Invented Trump’s Tariff Policy That Shook Global Markets?

Meet Peter Navarro

Tariffman

Trump’s New Tariffs in Cartoons from Around the World

The U.S. Shuts Down Programs Investigating Russia’s Crimes in Ukraine

Military Atrocity Initiative Closed, Data on Child Deportations Frozen, Cooperation with The Hague Halted