Microsoft is formally ending support for Skype, encouraging users to switch to Teams—its enterprise platform designed for collaborative work.

This marks the end of a story that began with a technological revolution: in the early 2000s, Skype gave millions of people around the world the ability to talk and see each other online—for free. It became more than a product: it became a verb, a habit, an infrastructure. But much has changed since then. Ownership shifts, corporate consolidation, technological missteps, and delayed updates stripped Skype of its leadership. SFG Media examines how Skype emerged, why it was revolutionary, and how it was ultimately pushed out of its own niche.

How the Team That Would Create Skype Came Together

In May 1999, the Swedish telecom company Tele2 launched an entertainment web portal called EveryDay.com. The project was led by Swede Niklas Zennström and Dane Janus Friis. The development was outsourced to an Estonian team—Jaan Tallinn, Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu, and Toivo Annus, who headed the effort. This group would later become the core of the team behind Skype.

EveryDay.com failed to meet expectations, and Zennström and Friis soon left Tele2 to start their own company. The Estonian developers followed. Zennström, a physics graduate with a background in management, became CEO. Friis, who had never earned a high school diploma, focused on ideas. As colleagues recalled, "no one knew exactly what he did—other than constantly coming up with crazy concepts."

Tallinn, Heinla, and Kasesalu had known each other since Soviet-era Estonia—they studied together and shared a passion for programming and hacking. In 1989, they founded Bluemoon and released Kosmonaut, the first Estonian computer game to be sold internationally. But by the late 1990s, the gaming business had withered, Bluemoon went bankrupt, and its founders were looking for freelance work. To land the Tele2 contract, they learned PHP in a matter of days and delivered the best-performing test assignment. Toivo Annus, described by colleagues as "painfully direct," was widely regarded as the best team lead in the country.

In 2000, the new company launched Kazaa—a peer-to-peer file-sharing service. Its decentralized architecture made it nearly impossible to block. The software quickly became one of the most downloaded programs on the internet. But legal trouble followed: millions of users were trading pirated content, and the entertainment industry filed lawsuits. The founders eventually sold Kazaa and paid over $100 million in settlements.

Niklas Zennström.

Janus Friis.

The experience with Kazaa laid the foundation for the team’s next venture. They began developing a network where users could share Wi-Fi and access telecom services. One component was to be VoIP calling—but the services available at the time were so cumbersome that making a single call could take a day to configure. That’s when the idea emerged: to use peer-to-peer technology not for file sharing, but for voice.

The internet provider project was put on hold. The team shifted its focus to building a new VoIP application—and Skype was born.

Development took just eight months, thanks to the team’s cohesion. Most of the work was done in Tallinn, the management was based in London, and the company was registered in Luxembourg, which offered the lowest VAT rate in the EU.

Skype officially launched on August 29, 2003. The 20-person team celebrated the milestone in Stockholm by watching the documentary *Startup.com*, a chronicle of the dot-com collapse. On day one alone, the app saw 10,000 downloads; by October, the figure neared one million.

The name Skype came from "sky peer-to-peer." The original name was Skyper, but the domain wasn’t available—so it was shortened. The first logo was purple; the familiar blue came later, after user testing.

Investor Steve Juurvetson, an ethnic Estonian, later recalled: "I was amazed by how such a small team handled so much. Maybe it came from their Soviet background—when you had no resources, you had to write code that was clean, economical, elegant."

Skype Was a Revolution—And a Headache for Telecoms

Unlike ICQ or MSN Messenger, Skype focused squarely on voice from the start. That became its defining feature and the core of its success: connections were made directly between users’ devices, without centralized servers. The only central server required was for authentication. This made the system highly scalable with minimal cost.

The app stood out for its simplicity: registration took just minutes, the interface was intuitive, and firewalls were bypassed automatically—the service "just worked." Even non-technical users could join a call in a matter of clicks.

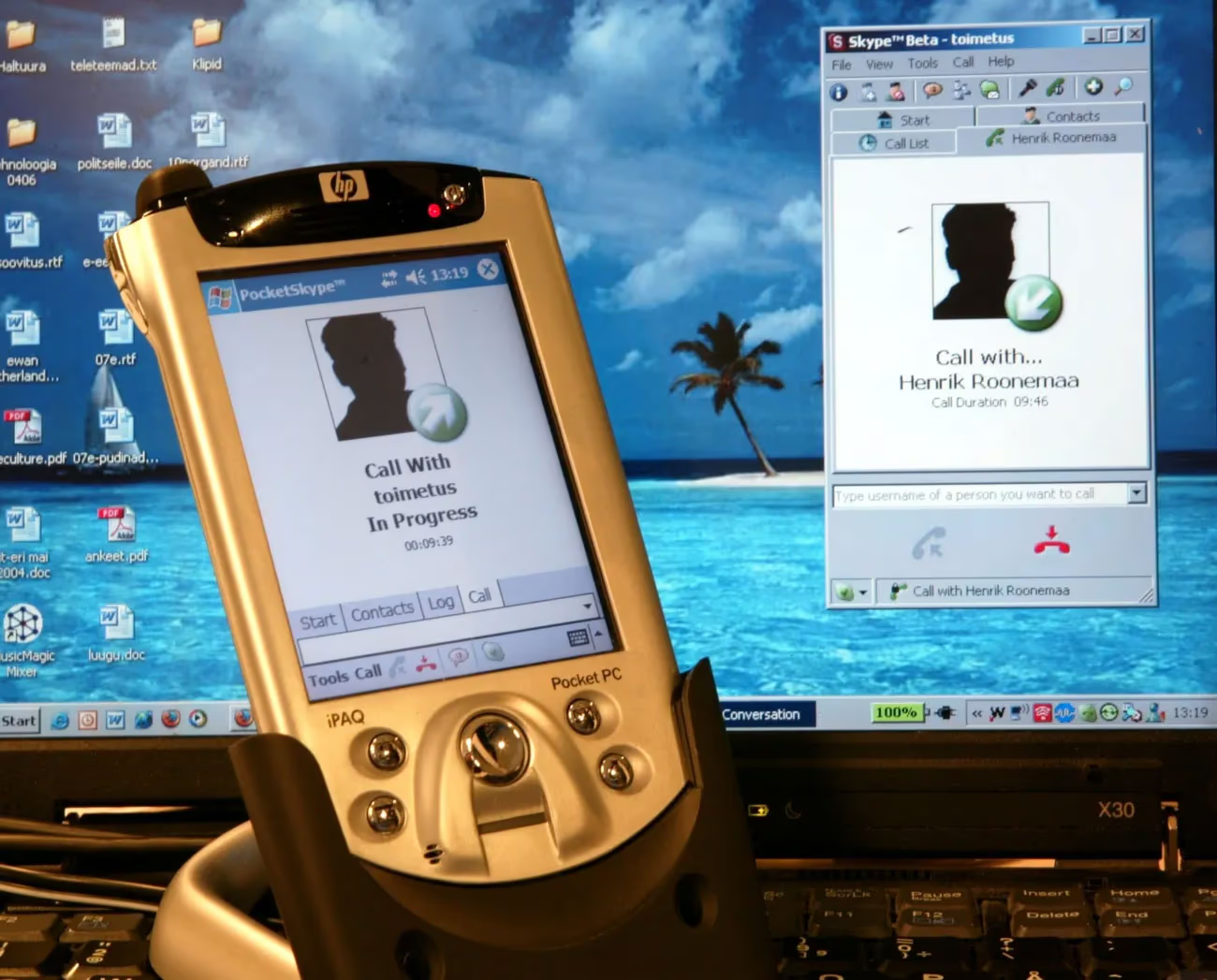

Demonstration of a call between Skype on a computer and a handheld PC. 2004.

Even the basic version of Skype included voice and text chat. Conference calls were added in 2004, followed by video calls in 2005. All of it was free—and often higher in quality than traditional phone services. For a small fee, users could also call mobile and landline numbers.

With mobile and international calls still expensive, Skype was a breakthrough. It quickly became the global leader in video communication, and the verb "to skype" entered the Oxford English Dictionary alongside "to google."

Skype became infrastructure for everything—from education and remote work to dating and startups. "You used to have to be a top executive to access video conferencing," recalled professor Barbara Larson. Professor John Naughton called Skype "a communications revolution."

From 53 million users in 2006 to 663 million by 2011. In 2019, it ranked among the six most downloaded apps of the decade. Initially available only on PCs, it soon spread everywhere—from Java phones to custom Wi-Fi handsets developed by Annus and Friis.

Telecom providers tried to block Skype; intelligence agencies complained they couldn’t intercept calls. The architecture was closed, the data encrypted. Governments in China, the UAE, Belarus, and Ethiopia restricted or outright banned the service.

"The telephone market is a racket built on rigged pricing and centralized dictatorship," Friis once said. "We couldn’t not disrupt it."

In classic startup fashion, the team found ways around restrictions: disguising traffic, omitting office addresses, and registering in Luxembourg. Lawyer Robert Miller, colleagues said, would delete letters from regulators without even opening them.

After the eBay Sale, Skype Began to Lose Its Identity

By 2005, major tech players—Google, Microsoft, AOL, and Yahoo—were developing their own competitors. Zennström and Friis decided to sell. In September, eBay acquired Skype for $2.6 billion, hoping to use it as a communication tool between buyers and sellers. If certain KPIs were met by 2009, the price could increase by another $1.5 billion.

But the integration flopped. eBay’s customers didn’t need Skype, and no new use cases emerged. The Skype team began building out enterprise features—group chats of up to 100 people, file transfers—but quality suffered, and tensions flared with PayPal.

Despite a growing user base, the service earned revenue only from calls—and it was far from highly profitable.

eBay’s corporate culture began to displace Skype’s startup spirit. The London-based management introduced procedures that made little sense in Tallinn. One particularly painful decision was to launch a censored version of Skype for the Chinese market.

One by one, the founders left. Annus was first to go. Zennström departed in 2007. Over two years, Skype saw four different CEOs. Friis, Heinla, and finally Tallinn followed. Tallinn left behind a "Million-Dollar Manifesto," criticizing the shift away from user-focused innovation toward "projects built for meetings."

Only Kasesalu remained.

In 2009, eBay decided to sell Skype. But it emerged that the core technology was owned by Joltid—a company founded by Zennström and Friis. The resulting legal dispute ended in a compromise: 70% of Skype was sold to a group of investors led by Silver Lake for $1.9 billion, with 14% going to Joltid. The founders returned to the board of directors.

Skype interface in 2009.

Skype Became Part of Microsoft—and Lost Its Identity

In 2011, Microsoft acquired Skype for $8.5 billion—its largest deal to date. The price was 40% above Skype’s internal valuation, but Microsoft hoped the move would strengthen its ecosystem.

Despite millions of downloads, Skype remained unprofitable—with $686 million in debt. Still, Microsoft integrated it into Windows, Xbox, and Office, replacing its own Messenger. Skype’s technology became the backbone of Lync, which was later rebranded as Skype for Business.

But analyst Trip Chowdhry’s warning proved prescient: "Microsoft’s culture will kill this company."

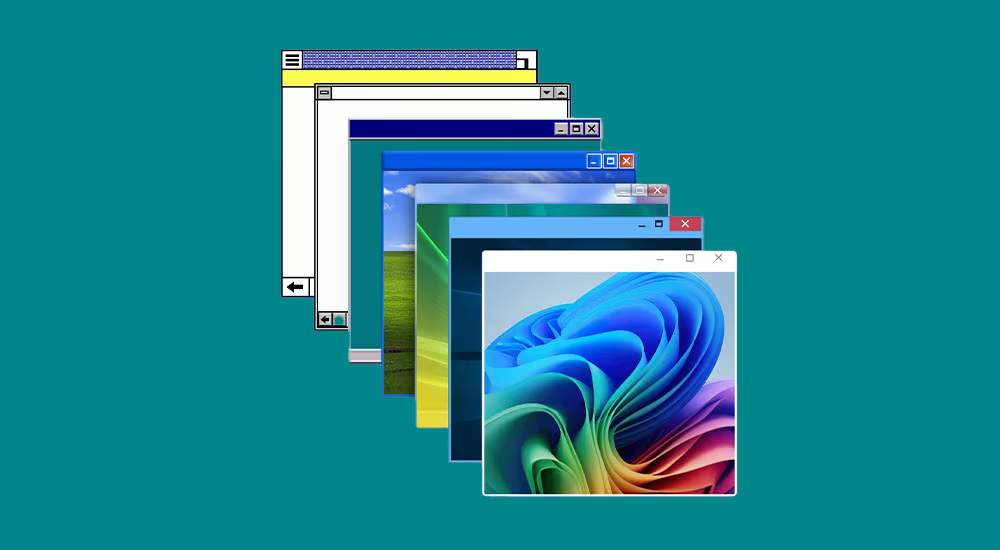

As the mobile era arrived, Skype’s legacy architecture began to buckle. In 2013, Microsoft abandoned peer-to-peer infrastructure; by 2014, VoIP was replaced. Reliability faltered. A 2017 redesign—visibly inspired by Snapchat—was widely rejected.

Skype became fragmented: two versions, two login systems, and persistent instability. By the time these issues were fixed, it was too late. Zoom, FaceTime, Discord, and WhatsApp had already pulled ahead. End-to-end encryption only arrived in Skype in 2018.

The pandemic offered one last opportunity—Skype saw 40 million active users in 2020. But Zoom won. By 2023, usage had fallen to 36 million.

Microsoft shifted its focus to Teams—a Slack competitor that replaced first Skype for Business and eventually Skype itself. In Windows 11, Teams came pre-installed. Both products shared the same team.

Today, Teams boasts 320 million monthly users. Skype is a product of the past. Users have been invited to migrate to Teams, preserve their data, and use remaining credits. But it’s no longer the same: Teams is built for the workplace, not everyday conversation.

Ctrl+Alt+Delete

Microsoft at 50

The Model Built by Bill Gates and Paul Allen Still Works, but the Company Has Learned to Respond to Failures