As the United States reassesses its global commitments and questions the established international order, Washington’s long-standing allies and partners are searching for alternatives to foreign-policy strategies overly dependent on the United States. Canada, South Korea, and the European Union have publicly signaled their intention to deepen ties with a broader range of countries. Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, for their part, are hedging against the unpredictability of American policy by strengthening other partnerships. Saudi Arabia, for example, has recently concluded a security agreement with Pakistan. The aim of these moves is to reduce vulnerability to abrupt shifts in bilateral relations and to gain greater room for independent foreign-policy decision-making.

For many states, such diversification of external ties has become salient only in recent years. India, by contrast, has followed this logic for decades. Since gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1947, balancing among different partners without binding itself fully to any single country or bloc has remained a cornerstone of Indian foreign policy. Over time, the approach has carried different labels—from nonalignment and bialignment to multialignment and omnidirectional engagement—but its substance has not changed. In periods of success, this strategy allowed New Delhi to avoid decisions dictated by a single partner and to leverage rivalry among states to strengthen its own position.

During the Cold War, India sought to maintain equilibrium in its relations with the United States and the Soviet Union, as well as with a range of smaller powers and members of the Non-Aligned Movement. In New Delhi, there was concern that either superpower—or both—could prove unreliable or apply pressure at a critical moment. After the Cold War ended, India preserved the core principle of not staking its future on a single partner. Like an investor managing a complex portfolio, the country continually rebalanced its relationships as new opportunities and risks emerged. At times, this meant a marked intensification of engagement with specific states—as in recent years, when India has drawn closer to the United States on a range of security, economic, and technological issues.

Pressure from Donald Trump’s second administration, however, has prompted India to reassess the weight of the United States in its partnership portfolio. Trump’s tariffs, reaching as high as 50 percent, calls for dialogue with Pakistan, and demands to curtail imports of Russian oil have heightened doubts about Washington’s reliability. These moves have also fueled debate over whether New Delhi’s orientation toward the United States has gone too far. For many Indian policymakers, the uncertainty generated by the actions of the American administration has only underscored the importance of diversification and of strengthening other ties—not only with U.S. allies such as France and Japan, but also with Washington’s adversaries, including Russia.

As a diversified foreign policy becomes the new global norm, India’s experience takes on particular relevance at a time when the international system is no longer defined by American unipolarity. New Delhi’s pursuit of multiple partnerships enabled the country to preserve maximum autonomy during the Cold War, when global politics were shaped by superpower rivalry, and continued to serve the same function in the U.S.-led order that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yet states now contemplating broader and more complex external ties must also reckon with the strategy’s drawbacks. India’s experience shows that diversification demands constant effort—regularly building, assessing, and revising relationships with different partners. Moreover, a patchwork of disparate ties offers fewer guarantees against aggression than formal alliance commitments. As a result, India has had to increase spending on its own defense, develop a nuclear deterrent, and in some cases exercise restraint in dealing with rivals. Without grappling with these lessons, countries seeking to follow a similar path today risk merely replacing excessive dependence on a single state with an equally problematic dependence on many.

Diversification as an Effort to Preserve Autonomy in a World of Competing Superpowers

India’s foreign-policy orientation took shape in a period when, much as today, technological breakthroughs and great-power rivalry were radically reshaping the global landscape. The state emerged from the partition of British India in 1947—at the dawn of the nuclear age and against the backdrop of a rapidly intensifying confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. The leaders of independent India, wary of new forms of colonial subordination, initially aspired to self-sufficiency. It soon became clear, however, that securing arms, economic assistance, and technical support was impossible without partnerships—and a degree of dependence on other countries. At the same time, policymakers in New Delhi feared that alignment with either the Soviet or the American bloc would not provide security so much as impose rigid constraints. The alternative was to construct a web of diverse partnerships capable of preserving India’s autonomy and preventing any single country or bloc from imposing its will.

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, accepted assistance from the United States, which hoped that a democratic India would serve as a counterweight to communism in Asia. In the early 1950s, New Delhi exploited Washington’s anxiety over the “loss” of China to the communist camp to secure economic and food aid. At the same time, Nehru sought to establish contacts with Moscow, but initially encountered limited interest from the USSR—Soviet leader Joseph Stalin viewed India as too closely oriented toward the West.

The drawbacks of lacking a partner capable of balancing U.S. influence soon became apparent. Seeking to cultivate a stable and peaceful regional environment, New Delhi opted for engagement with China rather than containment, a choice that irritated Washington. American policymakers criticized India’s recognition of the communist regime in China and its refusal to fully back the United States and its allies at the United Nations during the Korean War of 1950–1953. In the U.S. Congress, India’s nonalignment was seen as an immoral stance, effectively tantamount to support for the Sino-Soviet bloc. Lawmakers attempted to condition aid on demands to curtail contacts with communist countries or to grant the United States access to Indian raw materials and strategically important minerals, including manganese. Ultimately, in 1951 Congress approved legislation providing food aid to India without requiring changes to its foreign policy or the transfer of resources to the United States, albeit with an unspoken expectation that New Delhi would refrain from supplying strategic materials to the communist camp.

Shifts in the geopolitical environment of the mid-1950s widened the scope for maneuver. Seeking to expand its influence among states aligned with neither the United States nor the Soviet Union, Moscow offered India diplomatic, economic, and military support on terms that New Delhi found attractive, including assistance in developing a state-led industrial sector. The Soviet Union, for its part, accepted India’s principled refusal to side with any bloc. Nehru calculated that improved relations with Moscow would compel Washington to take India more seriously. That is precisely what followed: the administrations of Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy moved to strengthen ties with New Delhi. The United States was keen to ensure that democratic India did not falter as communist China gained ground. Once both Moscow and Washington signaled their readiness to cooperate, Indian policymakers judged their strategy vindicated. They had managed to play the two superpowers off against each other and secure economic aid, military supplies, and technological know-how—resources that supported state-building while simultaneously enhancing India’s autonomy through diversified external dependence.

War Revealed That Partnerships Do Not Guarantee Security

Diversification, however, did not provide deterrence. In 1962 India suffered a humiliating defeat when China attacked amid a dispute over the shared border. During the conflict, Moscow backed Beijing—its ally—rather than India, to which it was linked only through partnership. The United States and its allies provided New Delhi with military assistance, but it soon became clear that this support came with conditions. Washington sought to use the postwar moment to press India to settle its dispute with Pakistan over Kashmir, cut defense spending in favor of development, and abandon arms purchases from the Soviet Union. Had the United States remained India’s sole pillar, New Delhi might have had little choice but to accept these demands after the war. Yet the deepening Sino-Soviet split once again made India an attractive partner for Moscow. Rather than weakening India’s aversion to alliances, the episode reinforced the conviction among Indian leaders that any single partner could prove either unreliable—as the Soviet Union had—or inclined to exert pressure—as the United States had.

India’s war with Pakistan in 1965 further underscored the logic of a diversified course. When China threatened to intervene on Pakistan’s side, New Delhi once again turned to the United States. Washington warned Beijing against involvement, but at the same time suspended military and economic aid to both parties to the conflict, seeking to force them into a ceasefire. India, however, retained access to Soviet arms supplies, which policymakers in New Delhi took as further confirmation of the soundness of a strategy built on multiple partnerships.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who came to power in 1966, sought to broaden the country’s external anchors still further. She cultivated ties with states that shared India’s concerns about China, including Australia, Japan, and Singapore. Fearing a decline in U.S. interest in India while also taking into account Moscow’s efforts to draw closer to Pakistan, Gandhi aimed to reduce dependence on both superpowers. In the late 1960s she even attempted, unsuccessfully, to normalize relations with Beijing. The Soviet Union proposed that India conclude a formal treaty providing for closer ties and expanded assistance, but Gandhi declined, wary of excessive reliance on a single partner. Only in 1971, when India needed to deter potential Chinese intervention in another war with Pakistan, did New Delhi agree to sign the accord, shifting the overall balance toward the USSR after Washington moved from containing Beijing to engaging it.

The Soviet Union supplied India with military equipment and diplomatic backing during the war with Pakistan, yet this support, too, had limits—Moscow pressed Indira Gandhi to meet with Pakistan’s leader and avoid war, and later refused New Delhi’s request to publicly warn the United States against intervention. Seeking to offset the risk of excessive dependence on the USSR, Indian policymakers in the 1970s tried to repair relations with Washington. But India was no longer as valuable to the United States: after the U.S.-China rapprochement of 1971–1972, Beijing began cooperating with the American bloc against the Soviet Union, and Washington developed little economic interest in India. As a result, New Delhi turned to other partners, including countries in the developing world, while simultaneously accelerating its nuclear program, viewing it as a source of autonomous deterrence and an additional hedge against overreliance on the USSR.

This course proved resilient even amid domestic political upheaval. When the Indian National Congress lost power in 1977, giving way to the Janata opposition coalition, the new leadership did not abandon a diversified foreign policy. Prime Minister Morarji Desai criticized his predecessor, Indira Gandhi, for excessive dependence on the Soviet Union and advanced the concept of genuine nonalignment. It envisaged maintaining ties with the USSR while restoring relations with the United States, normalizing dialogue with rival China, and strengthening India’s own economic and military capabilities. After returning to power in 1980, Gandhi adhered to the same logic.

Yet as Indian governments sought to widen their circle of partners, they ran up against a serious constraint: many potential allies, especially in the West, did not regard India as central to their strategic objectives and therefore showed limited interest in engagement with New Delhi. As a result, throughout the 1970s and 1980s the country continued to rely heavily on the Soviet bloc. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, India was left without a fallback plan. Confronted simultaneously with foreign-policy and financial crises, New Delhi was forced once again to rethink and rebalance its partnership portfolio.

After the Cold War, India Was Forced to Rebuild Its Network of Ties

In the post-Cold War era, recalibration meant investing simultaneously in new partnerships and reviving old ones. In 1992 India established full diplomatic relations with Israel—a step long avoided because of ties with the Arab world and solidarity with the Palestinian cause. At the same time, New Delhi reinvigorated engagement in East and Southeast Asia, including with Japan and Singapore, whose strong economies were seen as catalysts for India’s own growth. Liberalization reforms, followed by the nuclear tests of 1998, strengthened the country’s economic prospects and defense capabilities. These decisions heightened global interest in India and expanded its range of potential partners—including, once again, the United States.

As in the 20th century, India’s foreign-policy course in the 21st has shown continuity regardless of which parties have held power in New Delhi. In 2003, the foreign minister of a coalition government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party described the motivation behind the strategy as “a desire for balance, noninterference, and autonomy of action.” That government, and the subsequent Congress-led coalition, strengthened ties with the United States while simultaneously expanding economic and multilateral cooperation with China. India also joined issue-based groupings, including the Quad with Australia, Japan, and the United States, as well as BRICS alongside Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa.

The current coalition led by the Bharatiya Janata Party has continued this diversification drive. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in office since 2014, has relied on a broad range of partners in search of diplomatic backing, defense supplies, export markets for Indian goods and services, raw materials—including energy and critical minerals—as well as investment, jobs, and technology. Like its predecessors, the present administration has deliberately reduced excessive dependence on any single partner in key sectors. Russia’s share of India’s arms imports by value, for example, fell from 76 percent in 2000–2004 to 36 percent in 2020–2024.

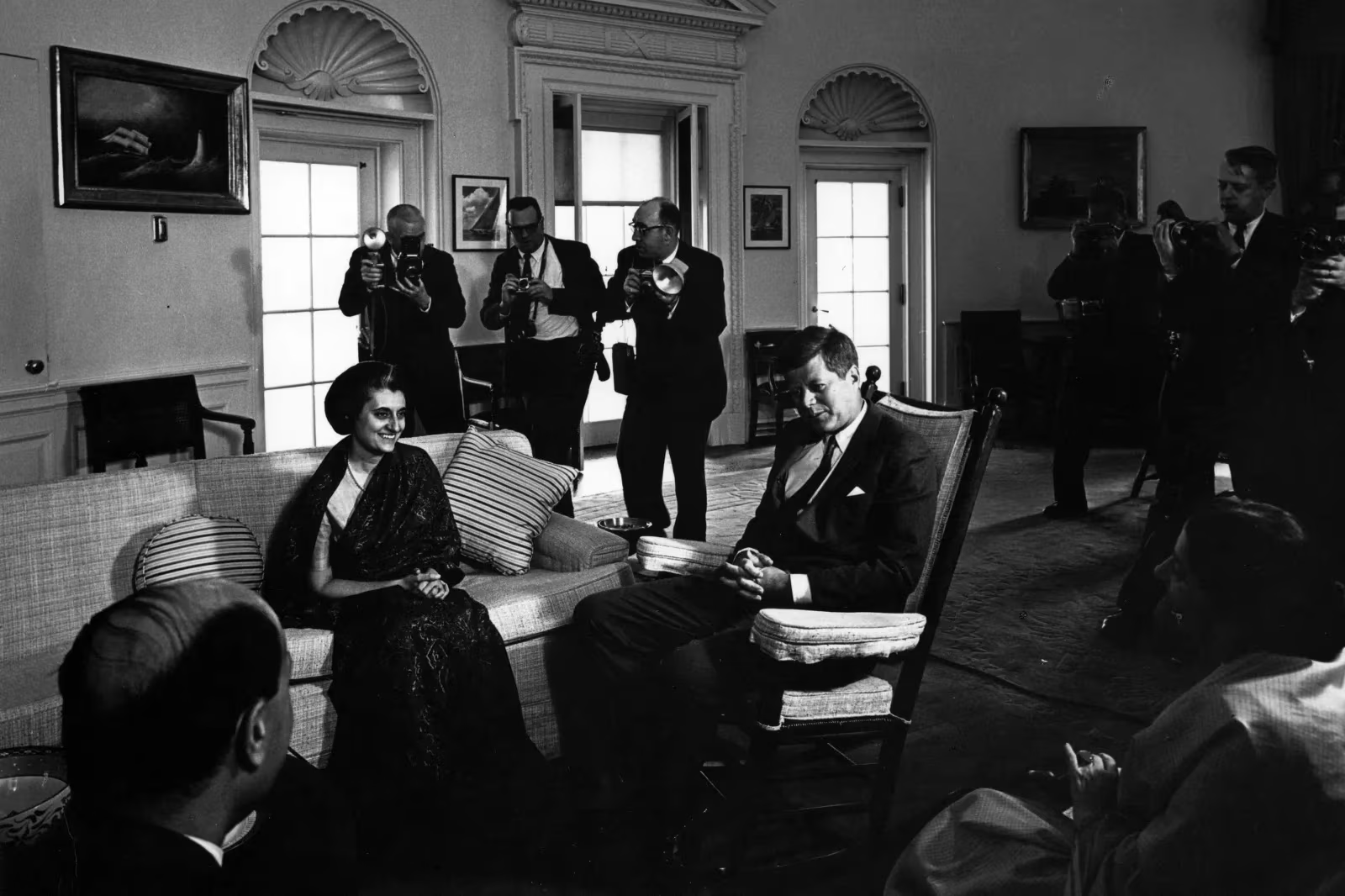

Gandhi meeting U.S. President John F. Kennedy in Washington, D.C. March 1962.

Despite the durability of the overall approach, the depth and scope of India’s partnerships have shifted as its interests and the pool of available partners evolved. In the early 2000s, New Delhi saw promise in closer engagement with China, but after military confrontations in 2013, 2014, and 2017—and especially after the events of 2020, when the first fatal military incident in 45 years occurred along the disputed Sino-Indian border—India’s stance became markedly more cautious. As tensions rose, India moved from trying to use China to balance its expanding ties with the United States and Europe toward seeking instruments to deter Beijing. Russia, itself increasingly dependent on China, has lost its former strategic weight for New Delhi. India does not intend to sever relations with Moscow, but the benefits of close partnership with Russia have diminished as access to advanced technologies and their development has taken priority.

By contrast, over the past decade the Modi government has steadily expanded defense and military-political, as well as economic and technological, cooperation with the United States, building on a shared interest in constraining China’s growing assertiveness. This strategic convergence has been reflected, among other things, in the increasing complexity of joint military exercises, including recent anti-submarine drills near Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, as well as in technological collaboration—for example, Google’s plans to establish a $15 billion artificial-intelligence hub in India.

This shift toward Washington, however, did not amount to an abandonment of diversification. Even as it drew closer to the United States, India’s leadership sought to preserve balance by deepening other partnerships. The Modi cabinet invested in ties with Indo-Pacific partners such as Australia and Japan, which share India’s concerns about China’s behavior. Relations with traditional European partners—France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—were refreshed, and new steps were taken to expand engagement with other European countries. To offset the growing weight of the West in its partnership portfolio, New Delhi intensified its search for opportunities in the developing world. India, for instance, sold anti-ship missiles to the Philippines, concluded an economic agreement to expand trade with the United Arab Emirates, and is working to secure access to critical minerals, including lithium, in Argentina.

Rapprochement With the United States Became Part of Balancing, Not an Abandonment of Diversification

In New Delhi, diversification is widely seen as having proved its worth. The ability to choose partners from a broad array of countries has helped India deter rivals and extract benefits from cooperation. It has also provided a hedge against the risks of excessive dependence when partners’ foreign-policy priorities shift. When Moscow effectively left India on its own during the war with China in 1962, when Washington took a similar stance during the 1971 crisis in India’s relations with Pakistan, or when Russia maintained neutrality during the China-India border clashes in the Himalayas in 2020, New Delhi still had alternative sources of support.

Even more important, reliance on multiple external sources helped foster India’s domestic capabilities, which in turn made it a more attractive partner. The national space program, for example, benefited from engagement with different powers. In the 1960s France and the United States provided access to expertise and technology, and after Washington imposed export restrictions, the Soviet Union stepped in to support India’s space ambitions. Today India is an autonomous and prominent player in the space domain. It has sent a mission to Mars, helps other countries launch satellites, cooperates with NASA on an Earth-observation satellite project, and works with the U.S. Space Force on an initiative to establish a semiconductor manufacturing venture.

Indian policymakers have learned that such an approach demands pragmatism rather than a pursuit of perfect autonomy. Although the country’s leadership seeks maximum freedom of action, achieving concrete objectives in practice often requires restraint and compromise. India, for instance, refrained from condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and did not publicly criticize Donald Trump when he imposed tariffs on India, prioritizing the preservation of beneficial partnerships over the impulse to voice open disagreement. Diversification, however, does not absolve a country from making choices. In critical and emerging technologies, when India must decide between Chinese and Western infrastructure, it opts for the West—not to curry favor with the United States, but to avoid deepening its own vulnerability to China.

At the same time, India has experienced the costs of diversification firsthand. When managed poorly, a web of disparate relationships can leave a country satisfying no partner and alienating all of them at once. Early in the Vietnam War, Washington expected India to temper its criticism of U.S. actions, while Moscow was dissatisfied that New Delhi did not condemn them more forcefully. Moreover, in sectors where India has not developed its own capabilities, a diversified course can result in dependence on multiple counterparties at once. Given that each operates according to shifting priorities, such dependencies expose India not only to a single country but to a broader array of rivalries and geopolitical risks. This is particularly evident in the Middle East, where several states—often in conflict with one another—simultaneously serve as India’s key diplomatic partners and as suppliers of oil, gas, investment, arms, and employment opportunities for Indian citizens.

Diversification can also lead to suboptimal outcomes. Seeking to avoid full dependence on a single supplier, India’s armed forces procure systems from multiple countries, some of which prove incompatible. Acquisitions from Russia, in particular, can constrain India’s access to more advanced technologies from the United States. Although this approach does not always maximize military effectiveness, New Delhi maintains it in part to preserve its own autonomy.

A more serious drawback is the questionable deterrent effect of diversification compared with formal alliances. It remains an open question whether China would have chosen to attack in 1962 had India been under the protective umbrella of either the Soviet Union or the United States. Recognizing this vulnerability, New Delhi signed an air-defense agreement with Washington in 1963 and a treaty with Moscow in 1971, both of which предусматривали consultations in the event of a Chinese attack. These arrangements signaled resolve to Beijing and provided India with a measure of insurance at the cost of some constraint on autonomy. In recent years, India has again drawn closer to the United States to counter a more assertive China. Even so, New Delhi would likely still reject a formal alliance with Washington, judging that its own conventional and nuclear capabilities can offset the deterrence shortcomings of diversification without binding commitments.

Ultimately, diversification is a strategy that demands constant attention. India’s leadership must continually assess how each external relationship affects the others. India, for instance, has been compelled to limit engagement with Iran in order to preserve the trust of Israel, the United States, and the Gulf states. At times, this balancing act falters. In September 2025, for example, Indian forces took part in Russian military exercises that rehearsed a scenario involving a nuclear strike on Europe. The move angered EU states at a moment when Brussels was seeking their approval for a trade agreement with India. At least two of those countries—Poland and Romania—subsequently initiated diplomatic and defense contacts with India’s rival, Pakistan.

Diversification Enhances Flexibility but Complicates Risk Management and Deterrence

Today, many countries besides India are attempting to craft foreign policies that allow them to hedge against risk without locking themselves into rigid commitments. They would do well to study India’s experience closely—New Delhi’s ability to play partners off against one another has helped strengthen national security, accelerate domestic development, and manage the unreliability of external actors. Yet it is equally important to recognize diversification’s vulnerabilities. The approach can leave a country exposed to the shifting priorities of multiple partners at once, force it to forgo cooperation opportunities in the name of autonomy, and provide weaker deterrence than a strong and dependable alliance.

Despite these constraints, India’s experience has only reinforced New Delhi’s preference for relying on multiple partnerships rather than an alliance with a single great power. Confronted with unexpected pressure from the United States during Donald Trump’s second presidential term, India is now seeking even broader diversification. This strategy can no longer resemble the Cold War era, when New Delhi balanced between the Soviet Union and the United States. Today, such clear alternatives are absent because of India’s comprehensive rivalry with China. In this context, New Delhi has made a pronounced turn toward Europe, accelerating negotiations on trade agreements with the United Kingdom and the European Union. At the same time, defense and economic-security partnerships with Australia and Japan are deepening, new avenues of cooperation with South Korea—including shipbuilding—are being explored, and steps are being taken to repair relations with Canada. Simultaneously, India is maintaining its partnership with Russia and attempting to stabilize ties with China, a posture illustrated in August 2025, when Narendra Modi met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin at a regional forum in China.