Jeffrey Epstein died more than six years ago, yet the criminal case in which he was accused of sex trafficking remains one of the most politically sensitive stories in the United States. Large parts of his biography are still shrouded in uncertainty. One of the central questions concerns the origin of the fortune that enabled him to acquire, among other assets, two islands in the Caribbean. This has given rise to numerous theories, including claims of ties to American, Israeli, or other intelligence services that allegedly financed his activities.

The New York Times Magazine undertook a large-scale investigation into his career: the reporters spoke with people from his circle, analyzed official and court records, and gained access to previously unpublished interviews, recordings, personal diaries, and correspondence. The magazine ultimately concluded that conspiracy theories are not required to explain his wealth. What proved decisive was a combination of luck, an ability to cultivate useful connections, and a willingness to operate on the edge—and at times beyond—the law. SFG Media recounts the key findings of this New York Times Magazine investigation.

Jeffrey Epstein grew up in a modest household in New York. His mother worked as a schoolteacher, while his father was employed as a gardener in the city’s parks department. From an early age, he displayed notable aptitude in mathematics and music, accompanied by a pronounced drive for wealth. He studied at Cooper Union and at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University, but never graduated from either institution.

In the mid-1970s, when Epstein was in his early twenties, he taught mathematics and physics at the elite Dalton School in Manhattan. The administration did not regard him as a particularly strong teacher, but he was popular with students—and with young female staff. In early 1976, at the invitation of the parents of one of his pupils, he attended a reception at an art gallery in Manhattan. There he was introduced to Ace Greenberg, one of the senior executives of the investment bank Bear Stearns, as a mathematical prodigy. Shortly thereafter, Epstein was hired by the bank and began dating Greenberg’s daughter.

In his resume, he stated that he held a university degree, although this was not true. When the deception came to light, Epstein readily admitted it and explained that without a degree he would never have been given the chance to prove himself. Bear Stearns’ management accepted this explanation and chose not to sever ties with him.

By the late 1970s, Epstein had acquired a reputation for maintaining relationships with a large number of women. He was also eager to help colleagues find sexual partners, including Jimmy Cayne—another senior executive at Bear Stearns. In return, Cayne introduced him to a circle of Wall Street’s wealthiest and most influential figures.

In 1980, at the age of 27, Epstein became a partner at Bear Stearns. In July, Cosmopolitan magazine named him “Bachelor of the Month.” That same year, the bank’s accounting department uncovered several violations in his work. During a trip to a conference in the Caribbean, he spent more than $10,000 in corporate funds on gifts for his then-girlfriend—jewelry and clothing. In addition, through her, he purchased shares in companies going public with Bear Stearns’ involvement, securing a substantial profit. The US Securities and Exchange Commission questioned Epstein over possible insider trading, but no charges were ever brought. Following an internal investigation, Bear Stearns fined him $2 500 and suspended him for two months. Epstein took this as a personal humiliation and left the firm.

At the time, he was in a relationship with Paula Heil—former Miss Indianapolis and an employee of Bear Stearns. Through her, he was introduced to the Lish family—British aristocrats and defense contractors. Epstein worked for them for only a few years: he was dismissed after it emerged that he was freely spending company funds on transatlantic Concorde flights and stays at luxury hotels.

Jeffrey Epstein in 1982 at a charity event benefiting the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation in Denver.

During the 1980s, Epstein spent a period designing tax-avoidance schemes for wealthy clients, primarily those he had come to know through his work at Bear Stearns. Among his partners was attorney John Stanley Pottinger, who years later represented women accusing Epstein of sexual abuse.

In the same period, Epstein persuaded millionaire Michael Stroll to invest $450,000—roughly $1.5 million by today’s standards—in an oil project that was never realized. The invested funds disappeared, the dispute went to court, but Epstein managed to avoid personal liability.

At the same time, he was involved in efforts to recover funds that had disappeared following the collapse of the brokerage firm Drysdale Securities, assisting the Spanish Obregón family. Notably, he secured this assignment through a romantic relationship with Ana Obregón. In the course of the investigation, Epstein traced the assets, by his account, to a branch of a Canadian bank in the Cayman Islands. He threatened the bank’s management with exposure, after which securities were handed over and used to compensate the Spanish side for its losses.

Epstein later became a consultant to financier Steven Hoffenberg, who operated in the field of mergers and acquisitions. Hoffenberg’s company turned out to be a $500 million Ponzi scheme, and he was eventually sentenced to 20 years in prison. Hoffenberg repeatedly claimed that Epstein was a co-conspirator in the fraud, allegations that Epstein consistently denied.

Epstein also generated substantial profits in the stock market. He assembled a group of investors and acquired a large stake in the chemical company Pennwalt, then announced plans to buy out the firm at a significant premium to its market price. The share price surged, and Epstein sold his holdings at the peak, locking in considerable gains. Investors later sought to force him to share the profits, but how those claims were ultimately resolved remains unclear.

By the second half of the 1980s, Epstein was already a millionaire and returned to Bear Stearns as a client. His personal broker, Clark Schubach, not only handled stock trades on his behalf but, according to accounts, also regularly sent his assistants to him.

In 1987, Epstein joined the board of trustees of the New York Academy of Art, founded by Andy Warhol. After Warhol’s death later that year, Epstein appeared at the top of the list of organizers for the memorial reception, cementing his place in the upper echelons of the American elite.

Around the same time, he met and soon became a financial adviser to billionaire Les Wexner—co-owner of Victoriaʼs Secret, Abercrombie & Fitch, and several other major brands. His clients also included billionaire Leon Black. In dealing with them, Epstein employed a similar tactic: persuading the client that their finances were in dire condition, that managers and even relatives were either incompetent or abusing their trust, and thereby securing virtually unrestricted control over the management of their wealth.

By the late 1980s, Epstein had purchased a villa in Palm Beach for $2.5 million, close to Mar-a-Lago—Donald Trump’s residence—and soon became a frequent guest at the estate. He began making substantial donations to political campaigns and expanding his circle of international contacts, including the future king of Saudi Arabia, Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, and Israel’s ambassador to the UN, the future prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

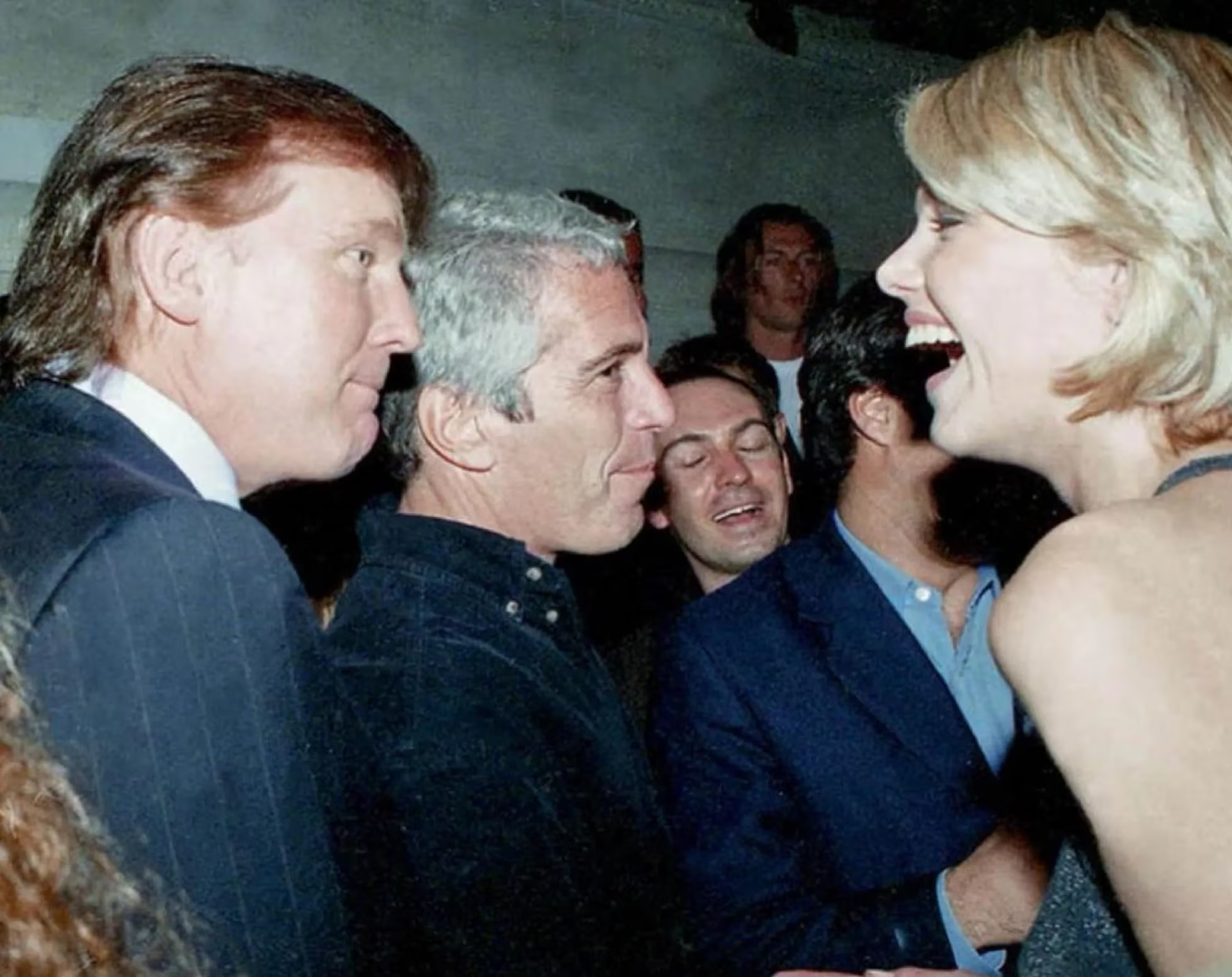

Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein. The 1990s.

Throughout the 1980s, Epstein maintained a long-term relationship with Swedish model Eva Andersson, who remained his steady partner. This, however, did not prevent him from regularly pursuing relationships with other women. Around 1990, their relationship came to an end. Shortly after the breakup, Epstein met Ghislaine Maxwell—the daughter of British media magnate Robert Maxwell, owner, among other assets, of the Daily Mirror and the Macmillan publishing house. After her father’s death in 1991, Epstein became a central pillar of support for her, including financially. According to testimony, Maxwell did not object to his numerous affairs with other women, including very young ones, and over time began seeking them out for him herself.

This period also includes a revealing episode involving Les Wexner—Epstein’s most important client. As Wexner was preparing for marriage, Epstein took part in drafting the prenuptial agreement and arranged for the document to be delivered by model Stacey Williams. He insisted that she dress “more sexually” and ask Wexner whether he was truly confident in his decision to marry.

Williams later said that in 1993 Epstein brought her to Trump Tower in Manhattan and introduced her to Donald Trump. According to her account, Trump almost immediately pulled her toward him and began touching her breasts and buttocks.

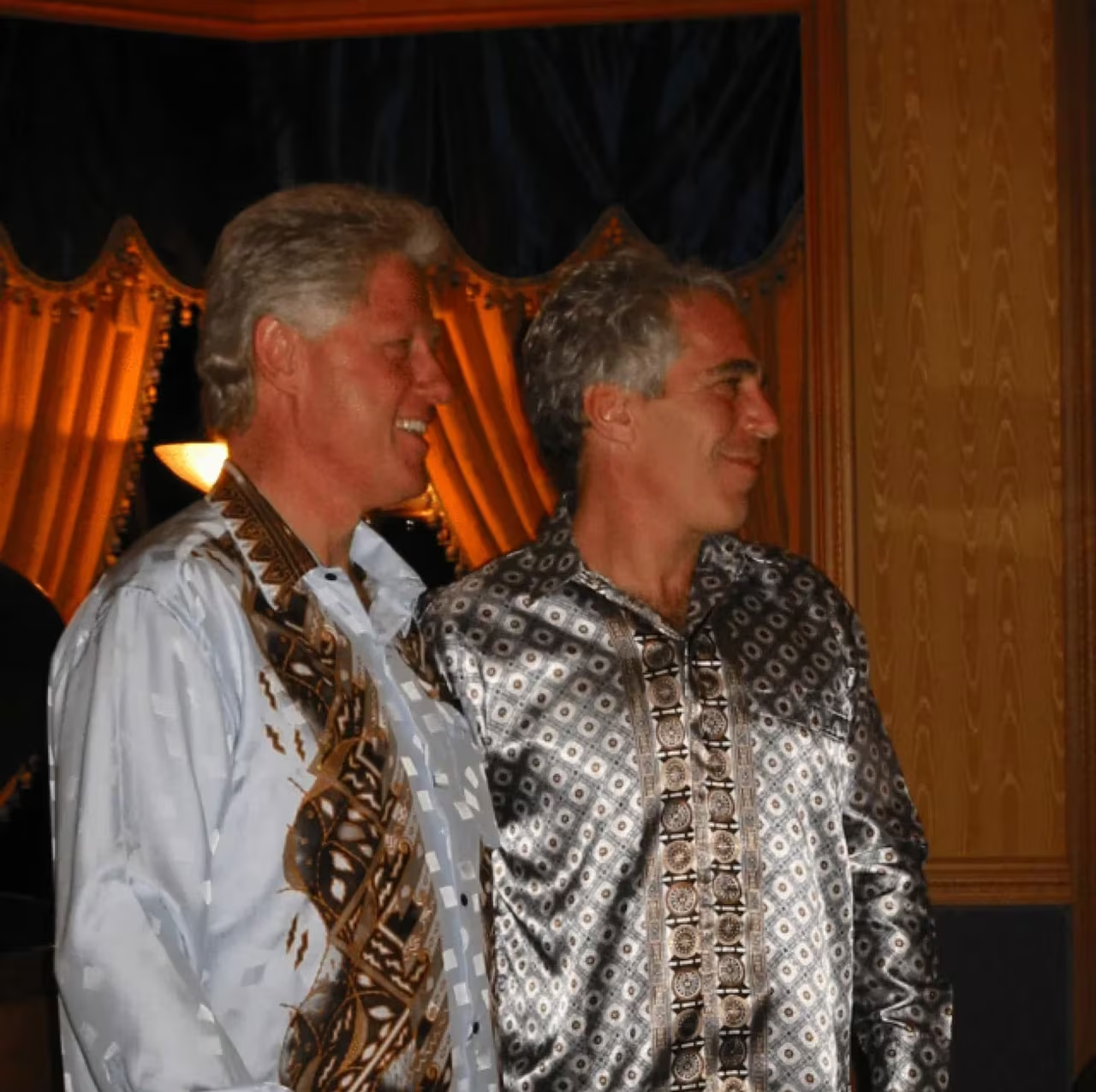

In 1993, Bill Clinton became president of the United States. Epstein donated to his election campaign and was personally introduced to the new head of state. During the same period, he maintained close ties with Lynn Forester—co-owner of TPI, then the largest telecommunications company in Latin America—whom Clinton appointed to one of the White House’s advisory commissions. Forester was in the midst of a divorce, and Epstein assisted her in securing the most favorable possible terms in the division of assets. In return, she arranged a private meeting for him with Clinton at the White House—the first in a series of such encounters. In 1995, when Epstein’s mother fell seriously ill, she received a handwritten note from the president bearing a brief message: “Hang in there!”

The First Batch of Epstein Case Files Has Been Released—13,000 Documents. What Have We Learned?

Trump Discussed a 14-Year-Old Girl With the Financier, and the First Complaint Reached the FBI as Early as 1996—but the Bureau Took No Action

The Release of the Epstein Archive Shifted Attention From Trump to Clinton

The Sexual Crimes Case Is Being Used as a Tool of Partisan Warfare in the United States

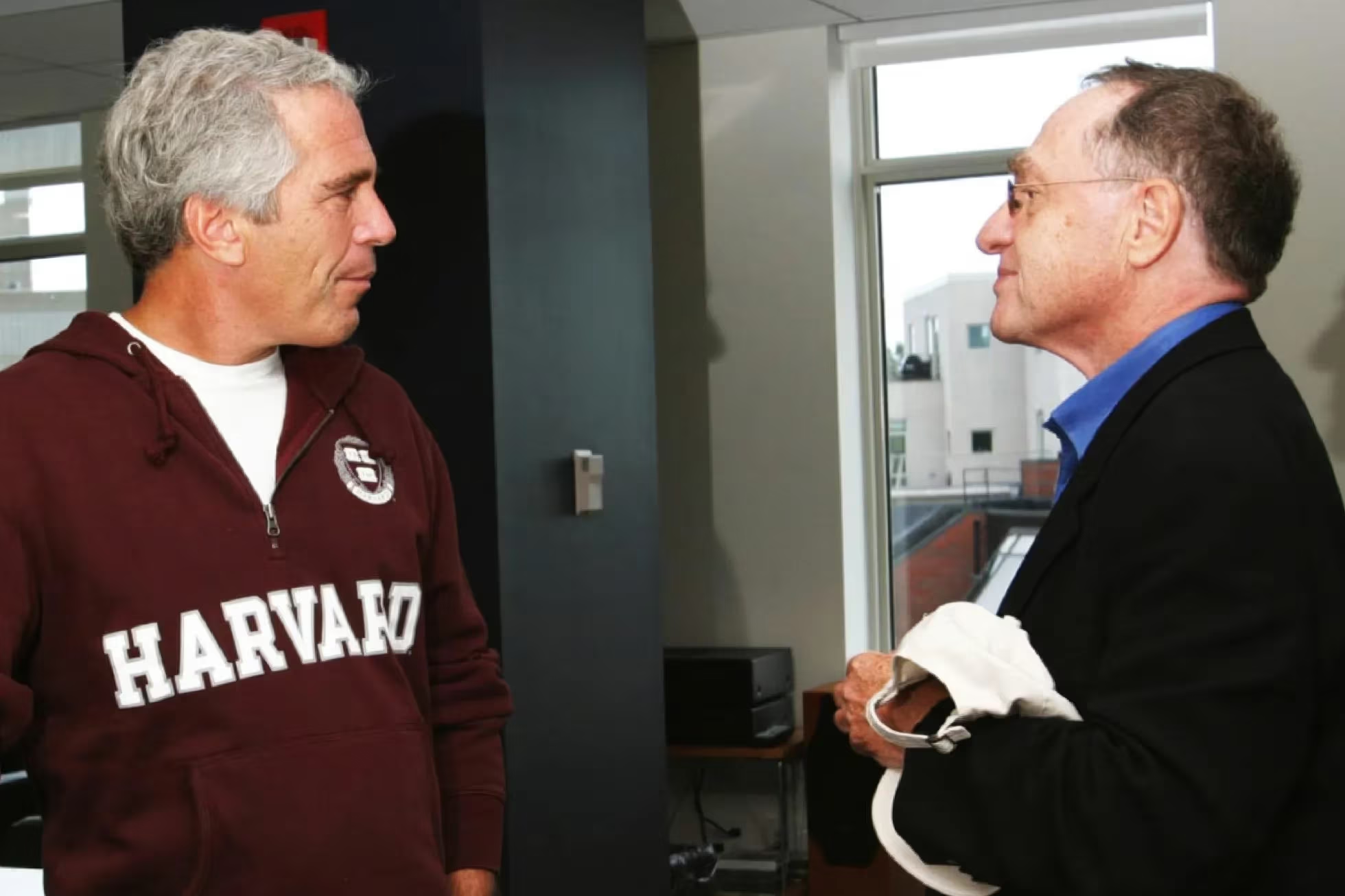

At the same time, the circle of clients who entrusted Epstein with managing their fortunes expanded to include Libet Johnson—the heiress to the Johnson & Johnson corporation. In parallel, he began making donations to Rockefeller family philanthropies and soon joined the board of trustees of Rockefeller University—one of the world’s leading centers for biological and medical research. Among his notable new acquaintances during this period were the Harvard economist and US deputy treasury secretary Larry Summers, who later went on to lead the department, as well as the prominent attorney Alan Dershowitz.

Jeffrey Epstein and Alan Dershowitz.

By the late 1990s, Epstein’s personal fortune exceeded $100 million and, in subsequent years, is estimated to have grown to as much as $300 million. A complex web of his personal and corporate accounts was concentrated primarily at JPMorgan. At the same time, according to investigative materials, bankers were likely aware that substantial sums from these accounts were being directed toward illegal activities, including payments for sexual services involving minors.

In 1998, Epstein purchased Little Saint James for roughly $8 million, an island in the US Virgin Islands—an autonomous US territory and a popular offshore jurisdiction. By transferring the registration of his assets there, he effectively freed himself from the obligation to pay taxes. It was this parcel of land that became known as “Epstein’s island.”

Little Saint James Island, purchased by Epstein in 1998.

Around 2004, a widely discussed rupture occurred between Donald Trump and Epstein. According to one account, Trump learned that Epstein was “recruiting” young female employees from his Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach and subsequently barred him from the property. In 2005, also in Palm Beach, the parents of a 14-year-old girl accused Epstein of sexually abusing their daughter. This triggered a prolonged and scandal-ridden investigation, during which his defense was led by attorney Alan Dershowitz—a lawyer who had argued as early as 1997 that laws protecting minors from sexual abuse were outdated, had lost their relevance, and in practice were applied only in “isolated high-profile cases.”

The case concluded in 2008 with a plea deal. Epstein pleaded guilty to soliciting sex from a minor and spent just over a year in custody—under conditions widely regarded as exceptionally lenient. His reputation was severely damaged, and the following decade was devoted to attempts to regain his former status and influence. In 2019, Epstein was arrested again—this time on charges of sex trafficking, including of minors, for the purpose of sexual exploitation. A month later, he died in a cell at a New York jail—according to the official account, by suicide.