European politics is undergoing a pivotal moment. Against the backdrop of inflation, an energy crisis, and an intense debate over migration, support is rising for parties that until recently were seen as fringe. The right has skillfully tapped into public fatigue with traditional elites, turning local grievances into a Europe-wide trend. New polls show that in France, Britain, and Germany—the region’s three largest countries—forces promising a radical rethinking of both domestic and foreign policy are moving to the forefront.

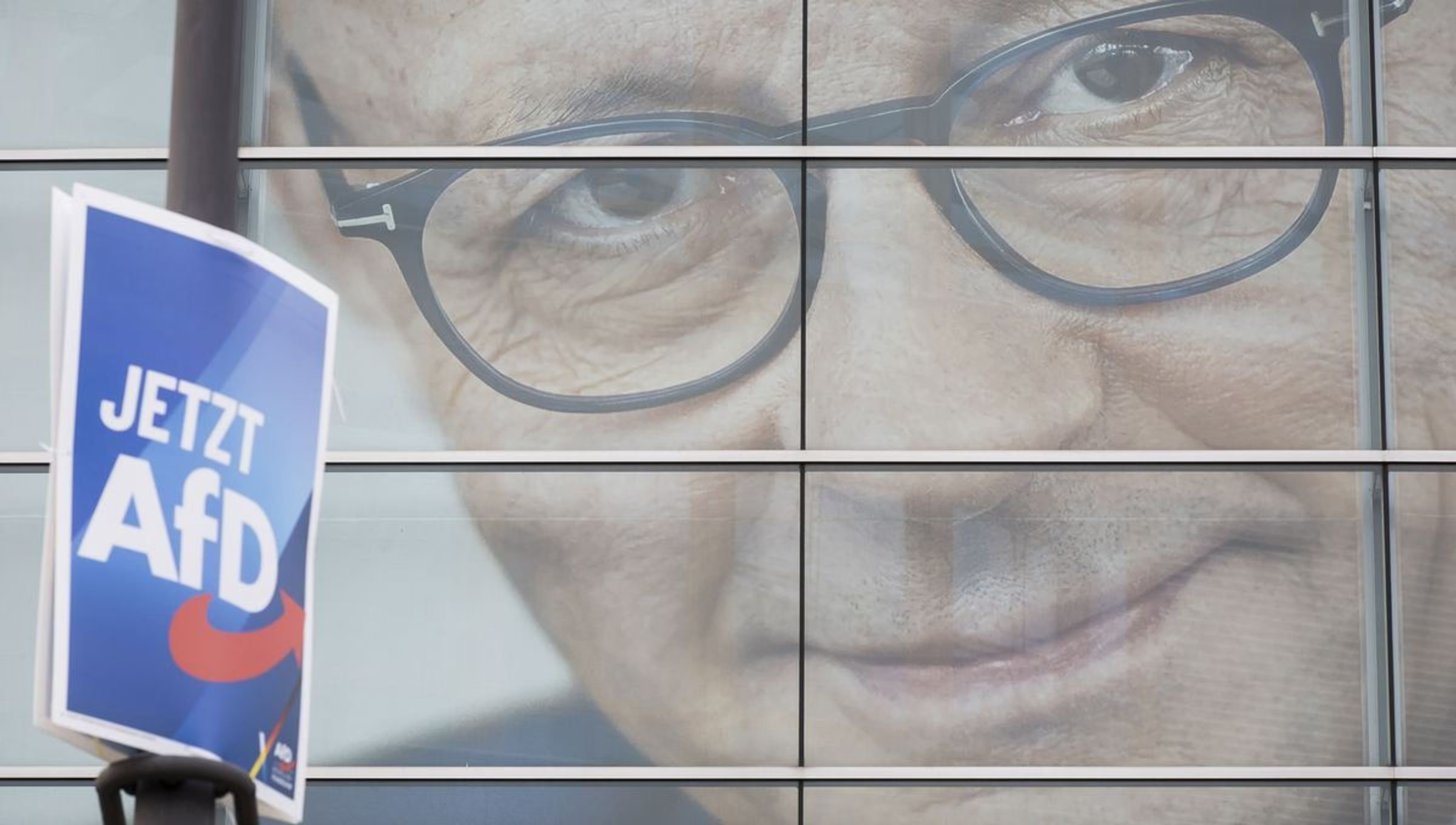

In Germany, Alternative for Germany (AfD) is gaining popularity, particularly among residents of industrial cities. Migration has become one of the central issues: in 2017, people born outside the country made up 15% of the population; today the figure is 22%. For comparison, in the United States, with nearly four times the population, the share is only 16%. AfD’s rise coincides with growing discontent over the energy crisis and inflation. In 2023–2024, rising gas and electricity prices hit industrial regions especially hard—areas traditionally loyal to the Social Democrats and Christian Democrats. According to the Bertelsmann Stiftung, up to 40% of AfD supporters believe the party reflects their socio-economic concerns better than the traditional forces. Added to this is foreign policy rhetoric: AfD calls for revisiting sanctions against Russia, setting it apart from centrist parties.

In Britain, fierce debates erupted over the government’s decision to house illegal migrants in hotels at public expense while their cases are processed in court. Against this backdrop, Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK party, has been gaining ground, with his ratings continuing to rise. According to YouGov, more than 60% of Britons oppose the practice of placing migrants in hotels. Scandals over the management of detention centers and growing budgetary costs have only deepened frustration. Experts at Chatham House note that Farage’s success could cement a shift in British politics: right-wing populists are beginning to pull voters away from the Conservatives, making migration the central issue in public debate.

In France, the National Rally has taken the lead in polls. Support for its leader, Jordan Bardella, stands at 36%. His popularity stems not only from anti-migration rhetoric but also from his appeal to younger voters: according to IFOP, more than 40% of voters under 35 back Bardella. Economic factors also play a role. France remains the EU’s largest importer of Russian liquefied natural gas, despite vocal declarations of solidarity with Ukraine. This contradiction fuels protest sentiment, which Marine Le Pen’s party is using to strengthen its position.

Union, Divided

EU Has Run Out of Options for New Sanctions Against Russia

Washington Remains the Only Actor Capable of Intensifying Economic Pressure

100 Days of Merz

Germany Faces the Rise of the Far Right, the Decline of Traditional Parties, and a Crisis That Will Shape the 2026 Elections

UK and EU Government Data to Be Moved Into Google and Microsoft Clouds

The Step Opens Access for U.S. Authorities, Deepens Reliance on Single Providers, and Undermines Digital Sovereignty

“From small English towns to the French countryside and Germany’s industrial centers, the same story repeats itself: many feel that traditional elites look down on them and ignore their concerns,” notes former EU diplomat Jérôme Gallon. The simultaneous rise of the right in three of Europe’s key countries could have far-reaching consequences. European think tanks warn that if these parties gain lasting influence in national parliaments and the European Parliament, the ability to coordinate sanctions policy against Russia will be at risk. Equally vulnerable would be the EU’s climate initiatives, as well as Brussels’ broader foreign policy line.

What until recently seemed like a local protest against migration is thus evolving into a systemic challenge to the European project. For the United States and NATO, it means the risk of weakening support for Ukraine and greater difficulty in forging a united Western position in the event of a prolonged conflict with Russia.

Over the coming year, elections to the European Parliament and national campaigns in Britain and Germany will reveal whether this is a temporary wave of discontent or the beginning of a long-term transformation of European politics. If right-wing parties manage to consolidate their gains, Europe could face a rethinking of core alliances and strategies—from energy security to EU enlargement policy.