The European Commission’s idea of building a “drone wall” was already raising doubts even before it managed to intercept a single Russian aircraft.

Russian drones have already violated the airspace of Poland and Romania, while unidentified aircraft—believed to be Russian—have been spotted over Denmark, Norway, and Germany. Against this backdrop, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, in her September State of the Union address, unveiled a plan for a new defensive system: a network of radars and interceptors to protect the EU’s eastern borders.

Yet both the metaphor of a “wall” and the concept itself have come under criticism. For the Baltic states and Poland, it appears a pragmatic response to a growing threat. But countries further from Russia point to its vulnerabilities: how realistic and justified is such an initiative, how does it align with NATO’s plans and national defense strategies, and is it an attempt by Brussels to expand its authority in security matters?

“Drones and countermeasures against them are an unquestionable priority,” French President Emmanuel Macron said. “But let’s be honest: there is no perfect wall for Europe. We are talking about a border stretching 3,000 kilometers. Do you really consider that fully achievable? The answer is no.”

Defense Commissioner Andrius Kubilius, a former prime minister of Lithuania, defended the project. He said the initial plan to protect Poland and the Baltic states from drones would cost around €1 billion and that a detection system could be deployed in less than a year. At the same time, he acknowledged that the very term “wall” is misleading: this is “not a new Maginot Line,” he stressed, recalling the French fortifications that Germany easily bypassed during World War II.

Skepticism also stems from the plan’s excessive ambition. “I hope no one sees the drone wall as a simple fix to our defense problems,” noted German Green MEP Hannah Neumann, a member of the Security and Defense Committee. “It won’t protect against cyberattacks, it won’t solve air defense or ammunition production, nor those deeper challenges tied to decision-making structures and rules of engagement.”

Europe Unprotected

In Recent Days, Germany Has Detected Drones Over Strategic Sites and Military Bases

Authorities Are Preparing a Law Allowing the Army to Shoot Down Suspicious Aircraft

The Danish Prime Minister Said Drone Flights Are Only the Beginning

The Security Situation in Europe Will Deteriorate

Southern States Oppose Funding Only the Eastern Flank

Divisions are deepened by the fact that Brussels, together with border states, is pushing for EU funds to finance the “drone wall.” But such funding requires the consent of all member capitals.

Southern countries have voiced discontent: Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis told fellow EU leaders in Copenhagen that European defense projects should benefit the entire Union, not just its eastern flank. Their objections prompted calls for “solidarity” from the more vulnerable members.

“We have shown solidarity over the past two decades—whether on Covid, the economy, or migration. Now it is time to show solidarity on security,” said Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo.

Divisions in Copenhagen were evident both in public statements and behind closed doors. According to one diplomat familiar with the discussions, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz sharply criticized the initiative, speaking in “extremely harsh” terms.

Europe Unprotected

The U.S. Deployed P-8 Poseidon Anti-Submarine Aircraft to Norway

Washington Steps Up Surveillance of Submarines Near Russia’s Borders After Reports of Drones in Europe

The Russian Vessel Yantar Collects Data on NATO Subsea Cables and Pipelines

Allies Fear Moscow Could Use the Information for Sabotage Against Critical Infrastructure

EU Approves Initiative, but Timing and Scope Remain Unclear

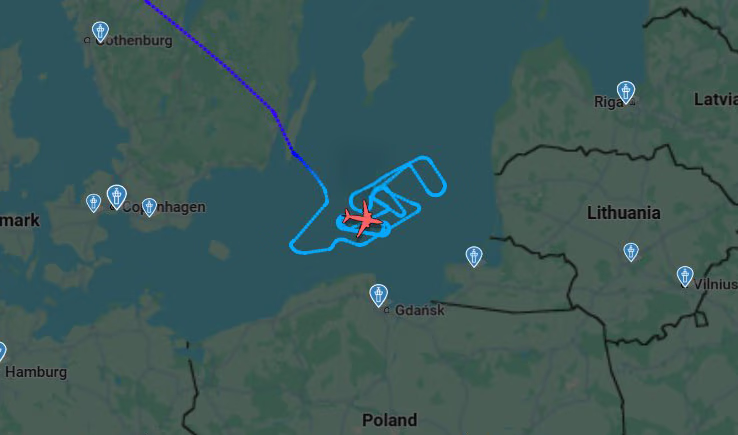

Despite disputes over the scale and even the name of the “drone wall,” there is little doubt about one thing: Europe needs stronger defenses against Russian drones. The Union still lacks technology to detect such aircraft effectively. When NATO shot down three Russian drones over Poland last month, it had to use missiles costing millions of dollars against Geran drones priced at roughly $10,000 apiece.

Although objections were voiced in Copenhagen, EU leaders ultimately endorsed the Commission’s defense initiatives, including the drone wall project. That means it will be implemented in some form, but the timeline, budget, and technical details remain uncertain. The name itself is also likely to change. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen last week spoke instead of a “European network of counter-drone measures.” Asked by a journalist why she avoided the word “wall,” she replied: “I don’t care what it’s called, as long as it works.”

Strengthening drone defenses appears a justified step at a time when Russia is regularly testing NATO’s resilience. But experts stress such measures are not a universal solution, especially if confrontation edges closer to full-scale war. “A wall can be effective regionally—for example, in the Baltic states a static line of defense could be built,” said Christian Mölling of the Bertelsmann Foundation. “But drones are only the ‘fingers.’ To prevail, you must strike the ‘head’: command centers, logistics, and production facilities.”

Border states harbor no illusions that a wall alone can stop Russian aggression. But in their view, steps to deter Moscow are necessary. “Of course we are realists… we do not expect that a wall on our border will eliminate threats one hundred percent,” Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk said. “Those seeking absolute security guarantees will not find them anywhere. As NATO and as Europe, we must find ways to maximize our safety.”