Migration policies once seen as the domain of the far right have now entered the European mainstream. Amid declining trust in institutions, growing voter discontent, and pressure from ultranationalist parties, centrists and social democrats are increasingly endorsing measures that were previously criticized by human rights advocates—from tighter asylum rules to proposals for outsourcing the entire system beyond EU borders.

This new political consensus threatens to undermine what for decades was considered a cornerstone of Europe’s legal order.

When Nicola Procaccini first entered the European Parliament six years ago, no one even wanted to share an elevator with him. He represented a far-right party whose anti-migrant rhetoric provoked open disdain. "My hand would hang in the air—they don’t shake hands with fascists," he recalls. Back then, migrant rights activists were invited to the chamber and greeted with applause.

Today, the atmosphere is entirely different. "Those who used to call our approach racist now say: 'Well, maybe there’s something to it,'" he says. His party—Brothers of Italy—now governs the country, and he leads the European Conservatives and Reformists group.

A similar shift is underway across Europe. Centrists and conservatives have coalesced around a vision of hardline control: streamlined deportations, tightened asylum rights, and the externalization of migration procedures beyond EU borders. Denmark’s "zero refugee intake" policy has become a model others aspire to emulate. Brussels has already signed an agreement with Bosnia and Herzegovina allowing European border guards to operate on its territory.

Vehicle checks at the German-Austrian border. Germany’s reintroduction of controls on its land border has drawn criticism, with many seeing it as a step back from the EU’s principle of free movement.

"There is a broad consensus across nearly all political camps," says Martin Hoffmann, an adviser at the International Centre for Migration Policy Development. "We will act tougher, we will be stricter."

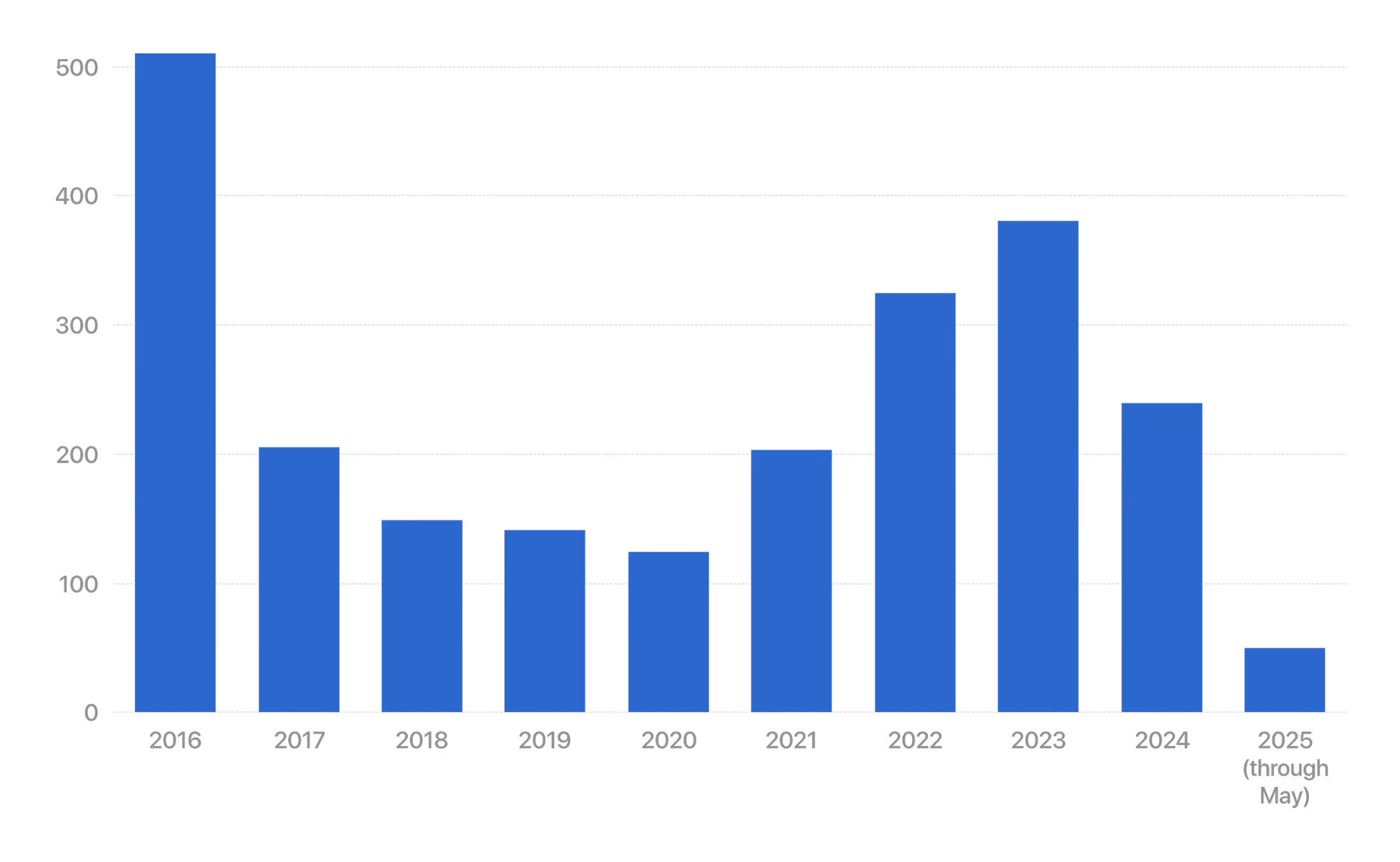

The shift in policy was driven by voter pressure—especially after the 2015 crisis, when Europe took in over a million refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. After the pandemic, migration numbers began rising again, though a decline has been recorded since 2024. According to Frontex, arrivals in the first five months of 2025 dropped by 20% compared to the previous year. At the same time, deportations are on the rise.

Still, tensions remain high. In a letter to EU leaders, Ursula von der Leyen pointed to an increase in migration from Libya to Greece and called for stronger border controls.

Irregular Migration to the EU, Thousands of People

According to Hoffmann, Europeans are driven less by migration itself than by a sense of lost control, rising prices, and fading prospects. The issue remains politically charged even when the numbers are declining. That’s why measures such as outsourcing asylum processing to third countries are gaining traction within the EU.

The United Kingdom’s initiative to relocate migrants to Rwanda was once met with criticism from the Council of Europe. Today, Giorgia Meloni’s proposal to send asylum seekers to Albania is already being discussed at the level of the European Commission. Although courts in Italy are currently blocking the scheme, von der Leyen has praised it as "out-of-the-box thinking."

An Italian Navy ship arrives at the Albanian port of Shëngjin in April. Italy has been seeking the option to transfer rescued migrants to the country.

In May, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, leader of the Social Democratic Party, met with Giorgia Meloni in Rome to express their joint support for a hardline approach. Despite receiving relatively few asylum applications, Denmark maintains one of the strictest migration policies in Europe. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz has called this approach "a model to follow."

Frederiksen and Meloni published a letter calling for a revision of the European Convention on Human Rights, adopted 75 years ago, arguing that it "overly restricts states’ ability to decide who should be deported." Eight countries joined the initiative, including Austria, Belgium, and Poland. "The fact that politicians from different political families have signed it shows how migration is bringing the European establishment together," Meloni noted.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen (left) and Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni at a meeting in Rome last month. Both advocate tough measures to limit migration to their countries.

The foundations of Europe’s human rights protection model are already eroding. "Yes, the agreements with Libya and Tunisia have helped reduce arrivals," says Camille Le Coz, director at the Migration Policy Institute. "But at the cost of serious human rights violations." In 2023, Tunisian authorities abandoned African migrants in the desert.

Domestic measures are also becoming tougher. Germany has reinstated border checks despite criticism from neighboring countries. Poland has suspended asylum procedures, accusing Minsk and Moscow of weaponizing migration as a form of hybrid warfare.

The migration shift may also affect those already living in the EU. The nationalist who won Poland’s presidential election campaigned on the slogan: "Poland First—Poles First."

It’s Happening Again

Pogroms, Beatings, Threats

Europe Faces an Unprecedented Wave of Antisemitism Not Seen Since World War II

Sydney Preacher Called Jews "Malicious" and "Murderers."

Court Ordered Him to Publicly Admit Racism, but Notices Have Yet to Be Published

Berlin Backs Deporting Asylum Seekers to Third Countries and Processing Claims Outside the EU

The Merz Coalition Tightens Controls, Freezes Family Reunification—and Faces Resistance From the SPD

Magdalena Czarzyńska-Jachim, the mayor of Sopot, noted that her city has long welcomed Ukrainians—even though Ukraine is not part of the EU. "Legal migrants are our neighbors," she said. "They are not criminals." What concerns her is how easily rhetoric begins to frame migrants as a threat.

Even longtime advocates of tough policies acknowledge the scale of the shift. Alexander Downer, former foreign minister of Australia, recalls how the EU used to criticize Canberra for sending migrants to camps in Papua New Guinea. "They were constantly lecturing me about how terrible we were," he says. "And now von der Leyen supports it."