Exactly 80 years ago, on August 6 and 9, 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These remain the first and only nuclear attacks on cities in history. Within seconds, tens of thousands of people were killed—those who had made no decisions about war, yet paid the ultimate price.

This photo series is a reminder of the consequences of choices for which civilians pay. And of a question that still goes unanswered: did anyone have the right to do this?

The photographs from these events are in black and white. But color makes no difference here—life in Hiroshima and Nagasaki vanished in the instant of the explosion. All that remained after the nuclear attack was ash, rubble, and shades of gray.

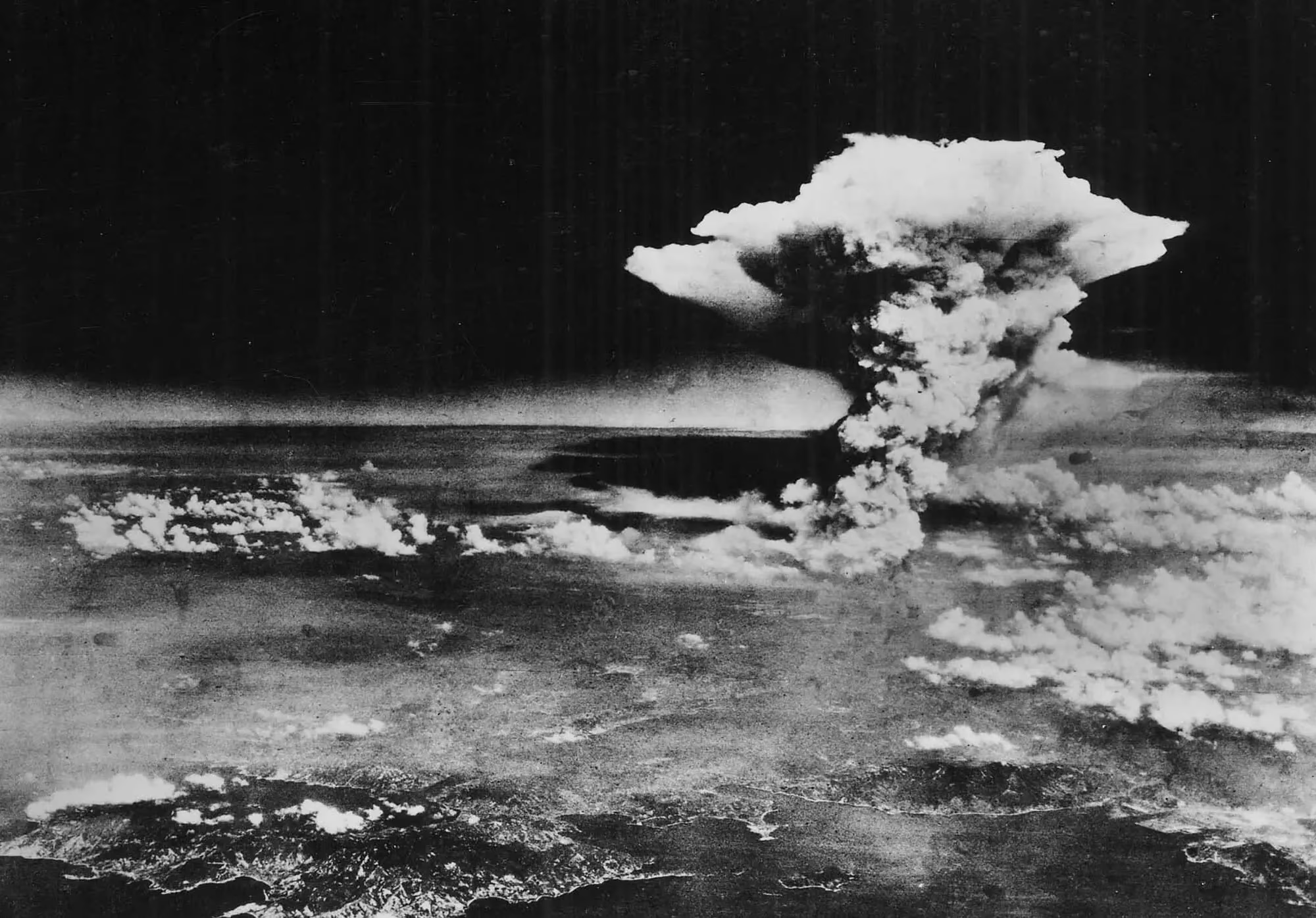

Aerial view of the devastation in Hiroshima. The primary target of the U.S. bomber is believed to have been the T-shaped bridge at the center of the frame.

On August 6 and 9, 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. The consequences were irreversible. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were almost entirely wiped out. People and animals perished, entire neighborhoods vanished. Those at the epicenter simply evaporated. These were the fastest deaths imaginable.

Hiroshima in the days after the bombing.

In front of the ruins of a building in Hiroshima.

By the end of 1945, the total death toll had reached around 210,000 people—140,000 in Hiroshima and 70,000 in Nagasaki. Many of them were children.

There are few photographic records from the first hours, but eyewitness accounts reveal the scale of the catastrophe. Survivors wandered with burned skin, damaged organs, blinded, dehydrated, their bodies covered in severe burns. In Hiroshima, thousands rushed into the river to escape the pain. Most of them drowned.

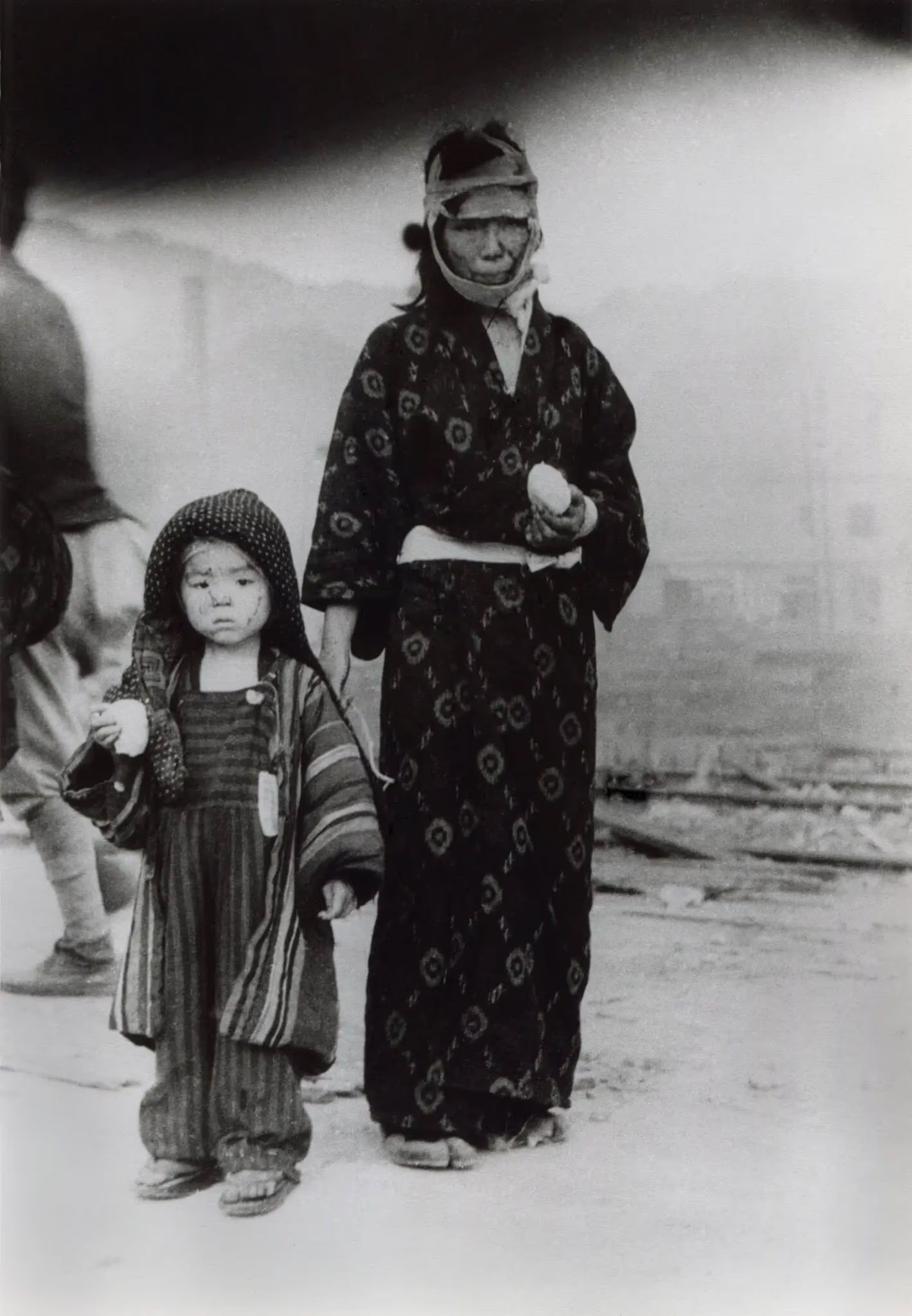

The heat of the blast seared the kimono pattern into this woman’s skin.

A man in a military hospital in Hiroshima. October 1945.

Children in Hiroshima four days after the bombing.

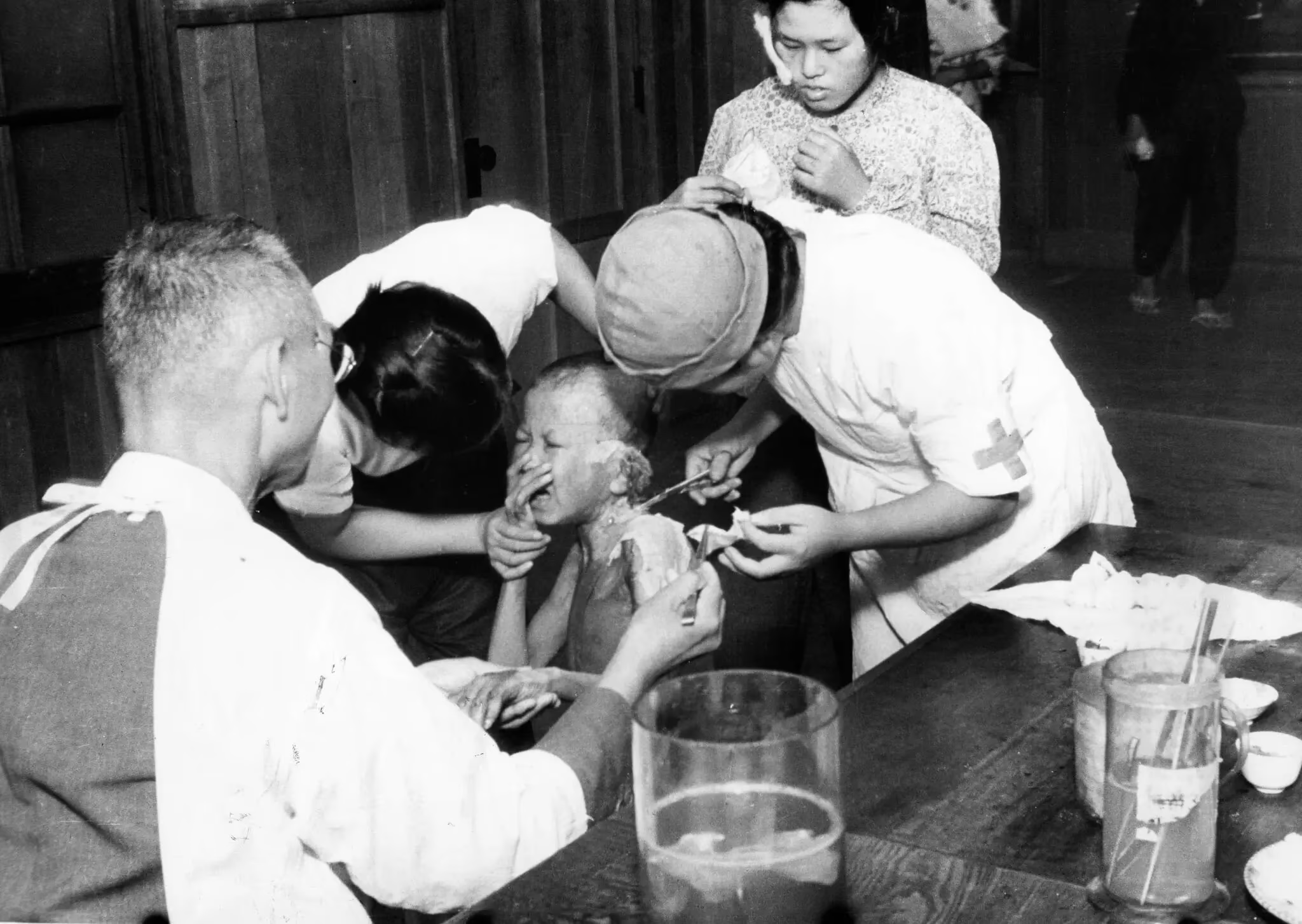

First aid being administered just hours after the bombing, about a mile from the epicenter.

The suffering didn’t end the next day. Maggots began to fester in open wounds. Relatives tried to remove them with sticks, but it was futile. People died from infections, internal bleeding, and radiation exposure. Even those who appeared unharmed at first collapsed and died days later—suddenly, without explanation.

Those who survived were left with scars, with cancer, with isolation. They were known as hibakusha—survivors of the bombing—and for decades they faced discrimination. People refused to marry them, refused to hire them. They were seen as dangerous, as if radiation could be inherited.

A child receiving medical care in Nagasaki.

The blast flash left the silhouette of a staircase and a person imprinted on a wall in Nagasaki.

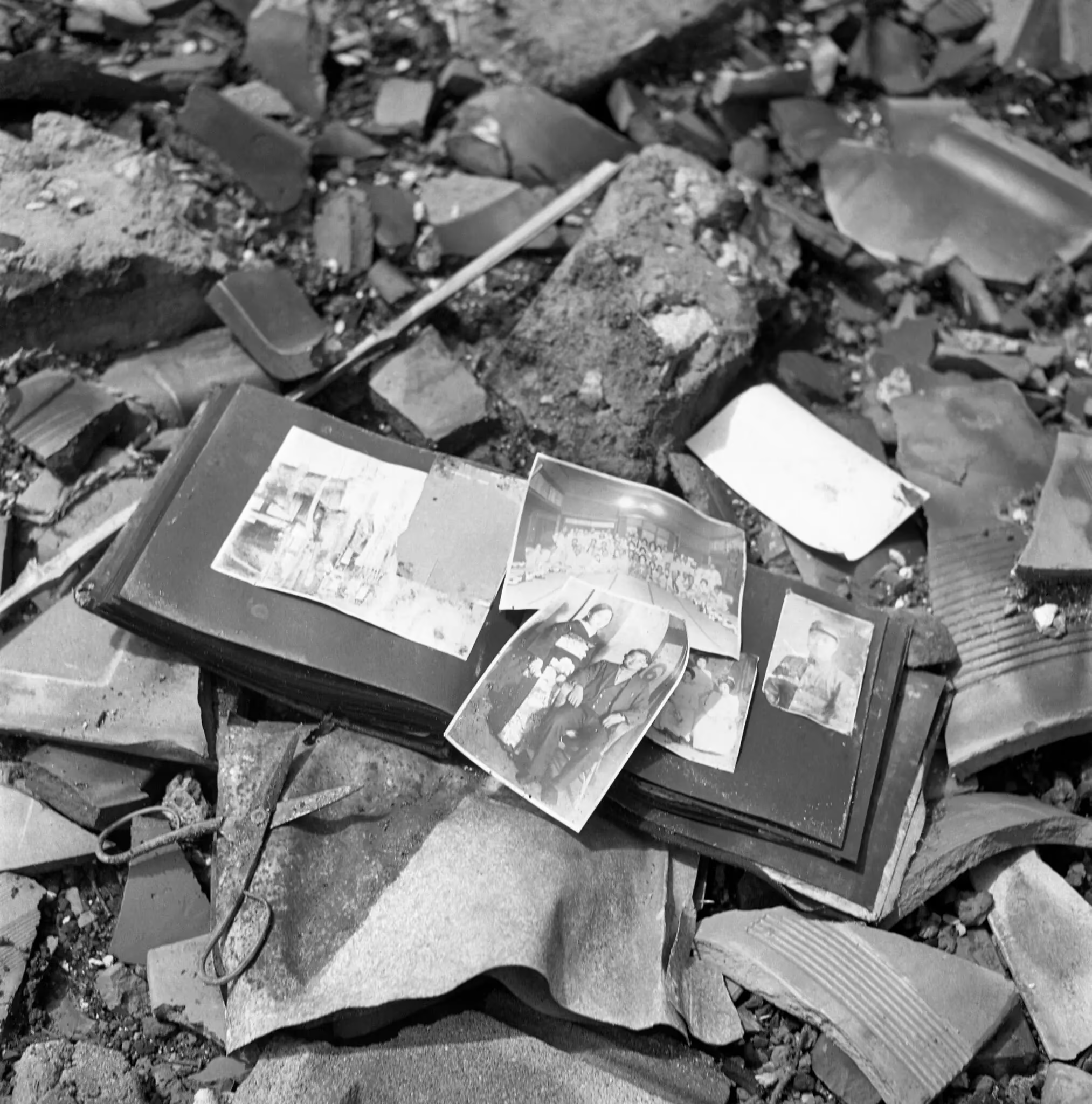

A family photo album amid the rubble in Nagasaki.

At the time, no one truly understood what it meant to expose an entire city to radiation. How do you live on poisoned land? How do you raise children when you don’t know what might be affected? How do you eat food grown under such conditions?

The U.S. described the bombing as a necessary step to end the war. On the morning of August 6, Hiroshima became a test field for a weapon meant to demonstrate American technological supremacy to the Soviet Union. Three days later, Nagasaki met the same fate—a port city open to the world, home to one of Japan’s largest Christian communities. Its destruction is far harder to justify.

Aftermath of the explosion in Nagasaki.

Cremation in Nagasaki. September 1945.

After the bombing of Nagasaki.

Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki, Japan, August 9, 1945.

Woman and child with rice balls in Nagasaki the day after the bombing.

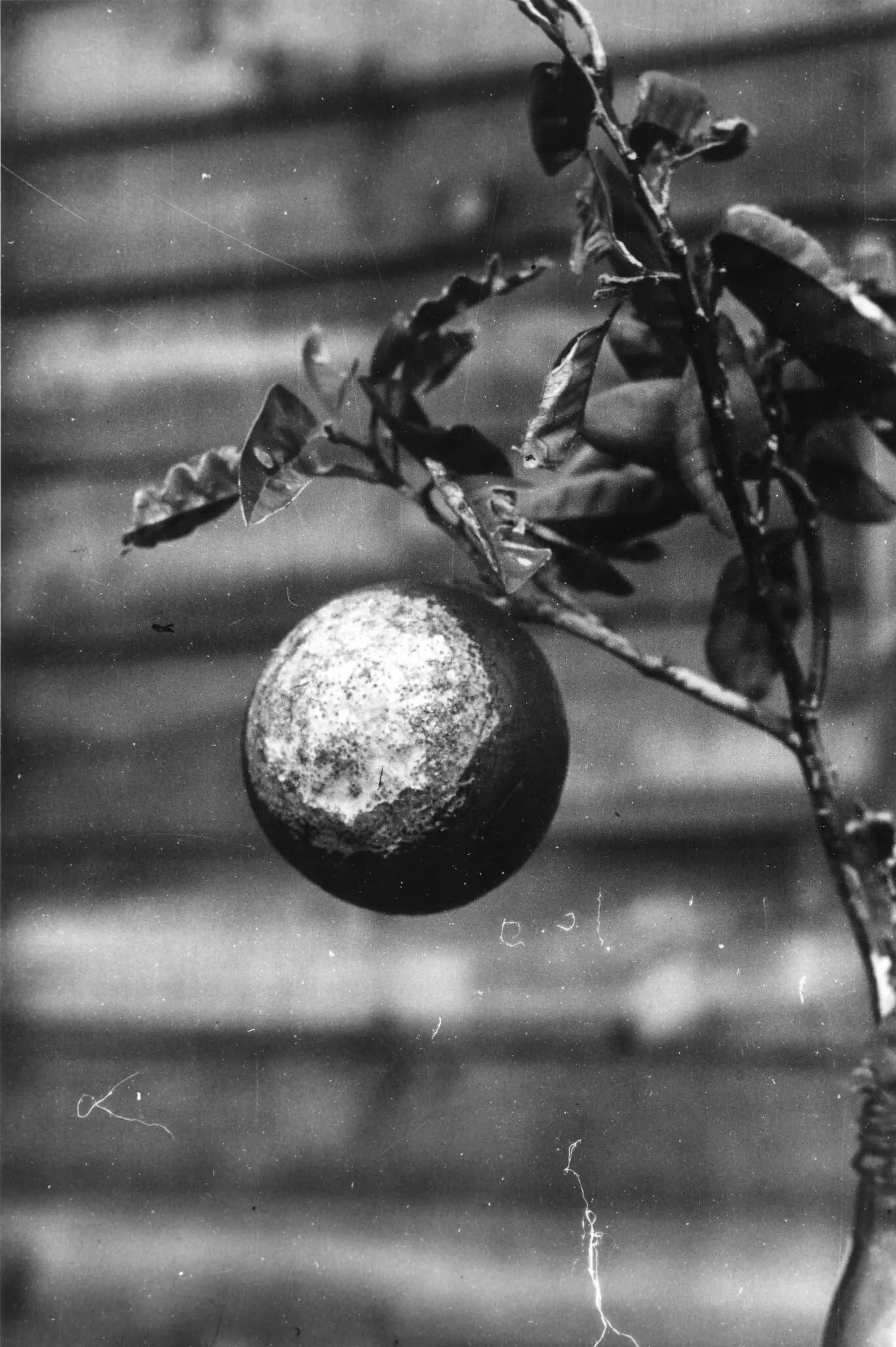

An orange, scorched on the side facing the nuclear blast.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were burned. First—by the blast. Then—by the fires that consumed the cities. And finally—by mass cremations. All that remained were bones.