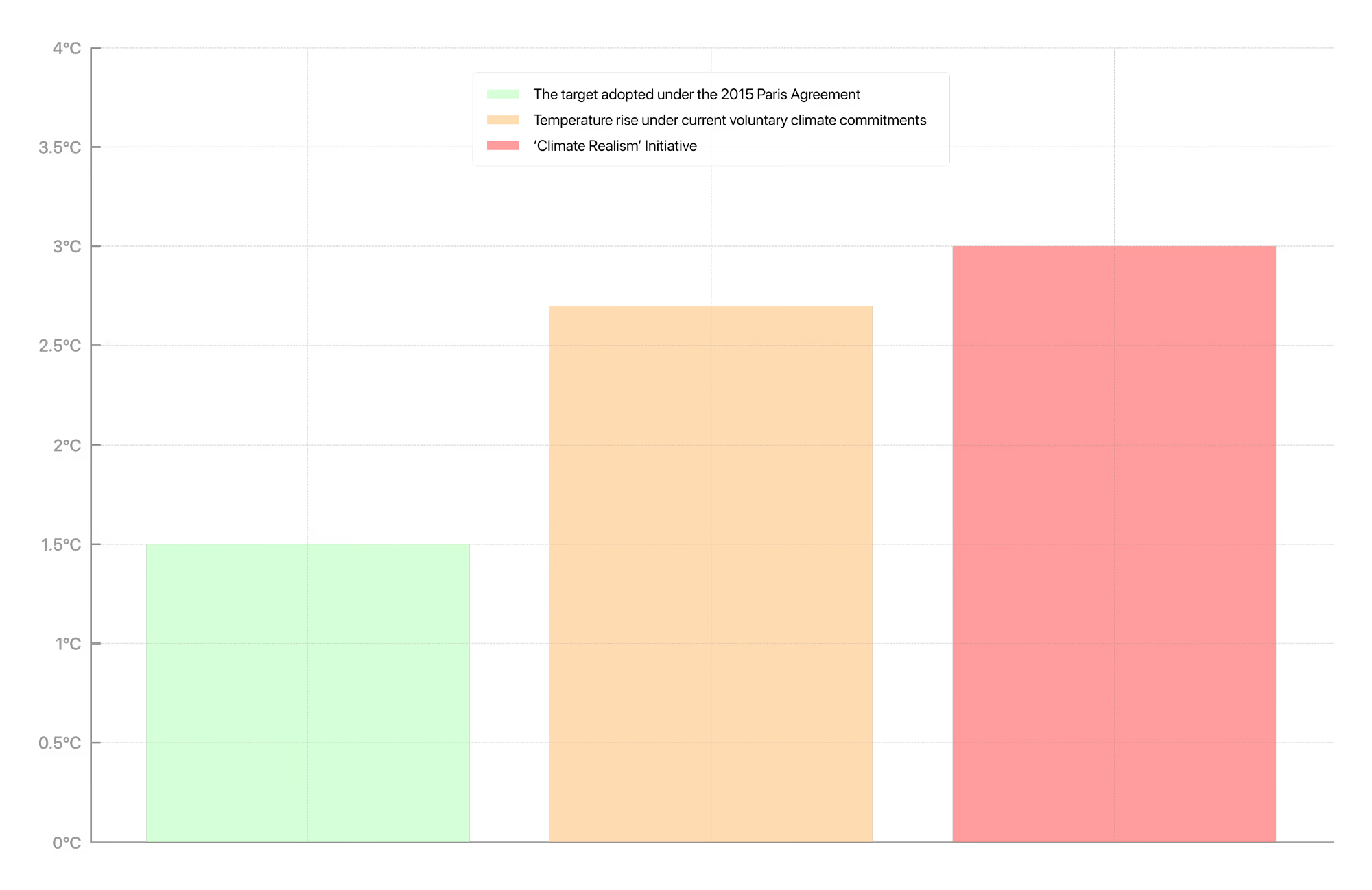

Not long ago, talk of 3 degrees Celsius of global warming sounded like science fiction. Today, it's a working hypothesis for leading analysts, policymakers, and investors. Between climate summits and natural disasters, the global agenda has quietly shifted: from trying to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C—to preparing for a world that's likely to warm by at least three. This so-called 'Climate Realism' is already shaping policy, finance, and security. But does it mean giving up the fight—or simply changing the goal?

Amid a steady stream of alarming climate news, a new consensus has quietly taken shape among U.S. think tanks and corporate leaders during the Trump administration. In their view, the goals of the Paris Agreement—to keep global temperature rise within two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit)—are no longer attainable. Now, they argue, we must prepare for a world that will warm by at least three degrees Celsius.

Citing "recent failures in global decarbonization efforts," Morgan Stanley analysts wrote in a research report last month that they now "expect a 3°C world." A similar forecast underpins the base scenario JP Morgan Chase uses to assess energy transition risks—the economic impacts decarbonization could have on investments in carbon-intensive sectors. That scenario assumes governments will take no new steps to curb emissions, and that warming could reach "3°C or more" by 2100.

The 'Climate Realism' initiative, launched by the Council on Foreign Relations, also assumes that average global temperatures are highly likely to rise by three degrees or more by the end of the century. In the essay accompanying the project’s launch, achieving net-zero emissions globally by 2050 is described as "utterly implausible."

Global warming by 2100

This shift in approach isn’t limited to the U.S. European policymakers continue to publicly insist on the 1.5°C target, but in private, many acknowledge that current global emissions trajectories point to warming of 2.5–2.9 degrees. According to Climate Action Tracker, if countries stick only to their existing climate pledges, temperatures will rise by approximately 2.7°C. EU officials warn that abandoning the 1.5°C goal would amount to capitulation. Meanwhile, China is building its own model, combining renewable energy expansion with rhetoric about "differentiated responsibility." For vulnerable nations, 3°C of warming would be a death sentence: even a one-meter rise in sea level would inundate vast areas of Bangladesh, Vietnam, and the Caribbean.

The conclusions analysts are reaching sound grim. Wall Street, predictably, is looking for investment opportunities and trying to minimize risks to client portfolios amid droughts, multi-meter sea level rise, and widespread crop failures. As journalist Corbin Hiar noted in E&E News, Morgan Stanley projects that in a 3-degree warming scenario, the $235 billion cooling systems market could more than double its annual growth—from 3% to 7% by 2030.

In recent years, banks—like many corporations—eagerly announced their climate goals. But the latest reports reflect something else: a widespread retreat from those commitments and a return to old corporate logic—making money. While governments poured money into the "green" economy, generously subsidizing new technologies, banks and big business made sure to ride the wave. But times have changed.

Now that performative environmentalism is out of fashion, financial institutions still have to account for climate risks—from rising insurance costs to supply chain disruptions. But calling themselves climate leaders? Not so much anymore.

Climate cynicism sounds much fresher—as articulated by the Council on Foreign Relations. In an essay outlining the new 'Climate Realism' initiative, its director Varun Sivaram—a former advisor to Biden-era U.S. climate envoy John Kerry—paints a picture of a world torn by climate crisis, in which "every country will pursue only its own interests," and the U.S., in his view, should do the same.

Flooding in Abbotsford, Canada, December 2024.

Fire in Santa Clarita, California, January 2025.

Against the backdrop of large-scale climate migration—which, according to the World Bank, could force up to 216 million people to relocate—and increasingly frequent disasters, the U.S., according to Sivaram, "must provide aid where possible, cooperate with other countries on resilience, and protect its own borders." In addition, he argues, America should "prepare for competition over resources and geopolitical influence in the rapidly melting Arctic region."

As greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise in developing economies, Varun Sivaram urges treating climate change as "a top-tier national security threat—on par with nuclear war and great power competition with China." He proposes joining with allies to punish countries that fail to reduce emissions. Acknowledging that such a strategy is "inherently unjust," Sivaram nonetheless insists on a climate policy driven by an America First logic. "The fact remains that foreign emissions threaten American territory," he argues—"and all the tools at the disposal of the U.S. and its allies—from diplomatic and economic pressure to military force—must be on the table."

This framing has drawn criticism. Climate activists and a number of scientists accuse the CFR of surrendering to the problem. In their view, accepting 3°C warming as inevitable undermines motivation to reduce emissions. Representatives of countries most vulnerable to climate change point to the moral responsibility of developed nations—and warn against abandoning the Paris goals. Many see climate realism as an attempt by the West to shed its obligations to cut emissions, shifting the burden to adaptation and damage control. "We cannot adapt to a catastrophe that is still preventable," said one of the authors of the latest IPCC report.

Another point of contention is the support for geoengineering, which Sivaram calls a possible way to prevent worst-case scenarios. Scientists warn that such technologies carry unpredictable consequences—from monsoon disruption to ocean acidification—and could trigger international conflict. More than 400 researchers have already signed a petition calling for a moratorium on unilateral geoengineering efforts without global oversight.

Still, the doctrine of climate realism is resonating in a world where cold calculation is replacing the old faith in decarbonization. The idea of treating climate as a national security issue is increasingly common in political speeches. In 2023, according to the World Meteorological Organization, global emissions hit a record 57 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent. Average annual temperatures rose nearly 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. At 3°C warming, coastal megacities will be at risk, yields of key crops could drop by dozens of percentage points, and millions of people will be forced from their homes. Even if outright collapse is avoided, the consequences could devastate entire regions.

Donald Trump and his inner circle don’t seem to view climate change as a real threat—or even a bad thing. Yet as the White House threatens to invade Greenland for its mineral wealth and sends people to prison camps in El Salvador, it is inadvertently building exactly the kind of climate-resilience infrastructure championed by the Council on Foreign Relations and its former alumni from the Biden and Obama administrations.

Climate forecasts are already grim. But grimmer still is a future where states and corporations fiercely compete for their share in a hotter, more chaotic world. The only thing worse than climate denial from the right may be a right that takes climate change seriously—and gains bipartisan support to put "America First" in a world where climate and conflict are already walking hand in hand.

The Heat Ahead

Marine Heat as the New Normal

What’s Behind the Oceans’ Unprecedented Warming?

AI’s Carbon Conundrum

The technology that could save the planet might also help burn it

Melting Glaciers Threaten Large-Scale Consequences for the Planet

Why Can’t the World Afford to Lose Its Ice?

Why Cloud Brightening Projects Face Public Pushback?

Climate Engineering Meant to Slow Global Warming Is Being Stalled Not by Technology—But by Mistrust From Local Communities

Less Ice, More Flowers

Antarctica is Warming Rapidly