In February 2024, Argentine President Javier Milei made a decision that draws a line under decades of historical silence: the National Archive released 1,850 documents related to the escape and sheltering of Nazi war criminals on Argentine soil. Although these materials were officially declassified back in 1992, until now they could only be viewed in a designated reading room in Buenos Aires. They have now been made accessible to the general public. From this collection of scattered reports, memos, newspaper clippings, and internal notes, a troubling picture emerges: for decades, Argentina provided refuge to individuals wanted by international tribunals—including some directly involved in the Holocaust and mass killings.

When Mossad agents abducted Adolf Eichmann from a street in a suburb of Buenos Aires in 1960, Argentine authorities publicly condemned the operation as a violation of national sovereignty. But behind the diplomatic outcry lay something else: someone within the security apparatus appears to have known Eichmann’s whereabouts and chose not to interfere. The archival documents do not so much confirm this outright as they strongly suggest it—the system knew, but acted selectively, shaped by political calculation, institutional fragmentation, and a lack of sustained political will.

Adolf Eichmann.

Of particular interest to the Simon Wiesenthal Center—which took part in negotiations with Argentine authorities—is the possible role of the banking group Credit Suisse. According to researchers, the bank may have helped transfer capital obtained by looting Holocaust victims to South America. These funds were likely used, at least in part, to finance escapes. While the archive contains no direct evidence, several references suggest plausible grounds for such hypotheses.

At the heart of the declassified materials are dozens of individual stories. Among them are figures wanted by international tribunals: Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, Klaus Barbie, Walter Kutschmann, Eduard Roschmann, Josef Schwammberger, Ante Pavelić. Some died in freedom, never facing justice. Others were captured only decades later. Each followed a different route, but nearly all relied on the same support system: forged documents, humanitarian and church cover, and the leniency of Argentine authorities.

Eichmann was one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, heading Department IV-B4 of the Reich Main Security Office. He oversaw the logistics of deporting millions of Jews to extermination camps. After the war, he escaped via the "ratline"—a clandestine route through Italy allegedly facilitated by Catholic networks and Austrian Bishop Alois Hudal. In Argentina, he lived under the name Ricardo Clement. It wasn’t until 1960 that Mossad agents located him, smuggled him to Israel, and put him on trial—the country’s first international prosecution for genocide.

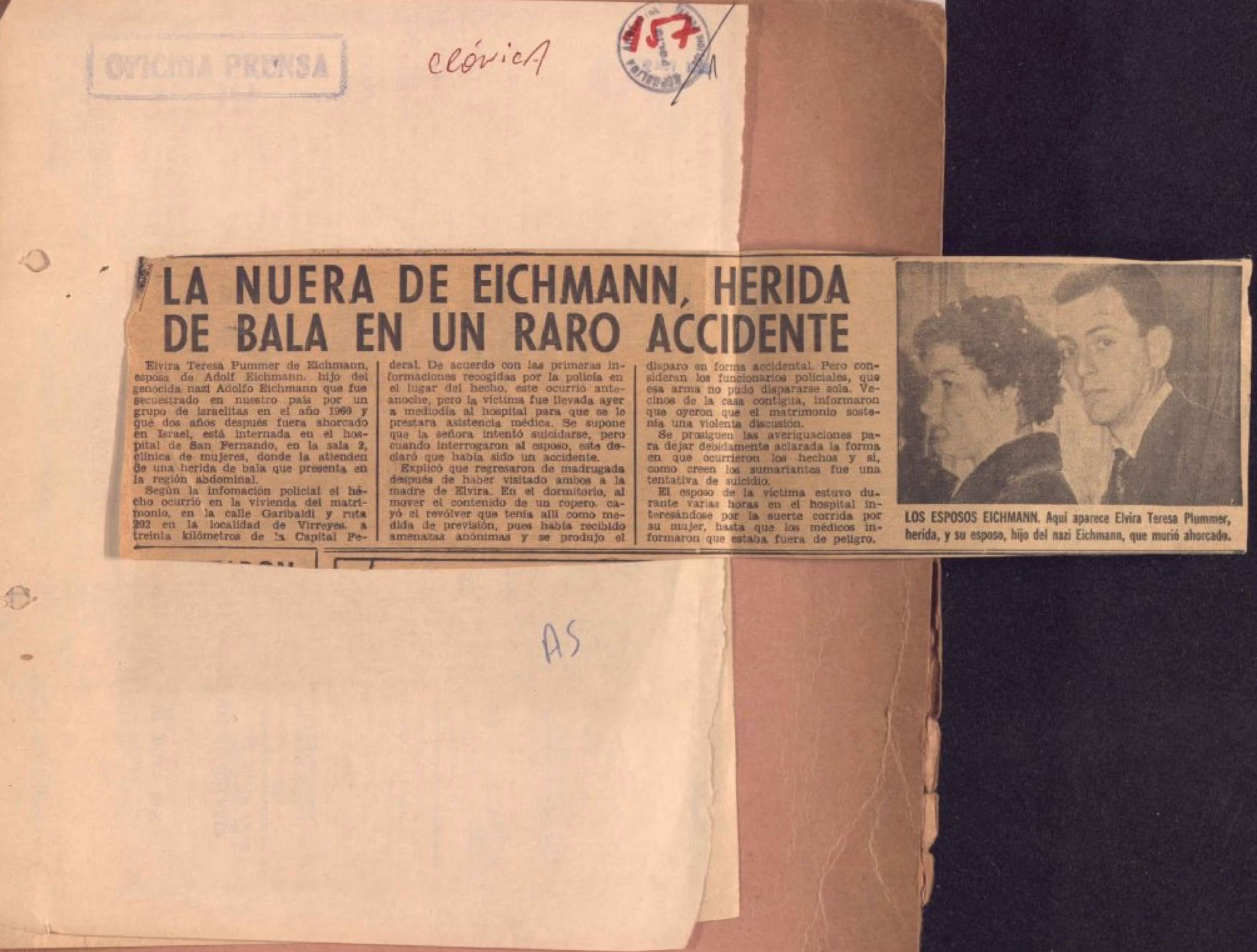

Josef Mengele.

Josef Mengele, the SS doctor from Auschwitz notorious for his horrific experiments on prisoners, also ended up in Argentina, where he lived under the name Helmut Gregor. In 1956, he obtained documents under his real name, effectively legalizing his status. After Germany requested his extradition in 1959, he fled to Paraguay and later to Brazil, where he died in 1979. His identity was confirmed only in 1985 through exhumation and genetic testing. Mengele died without ever facing a single conviction.

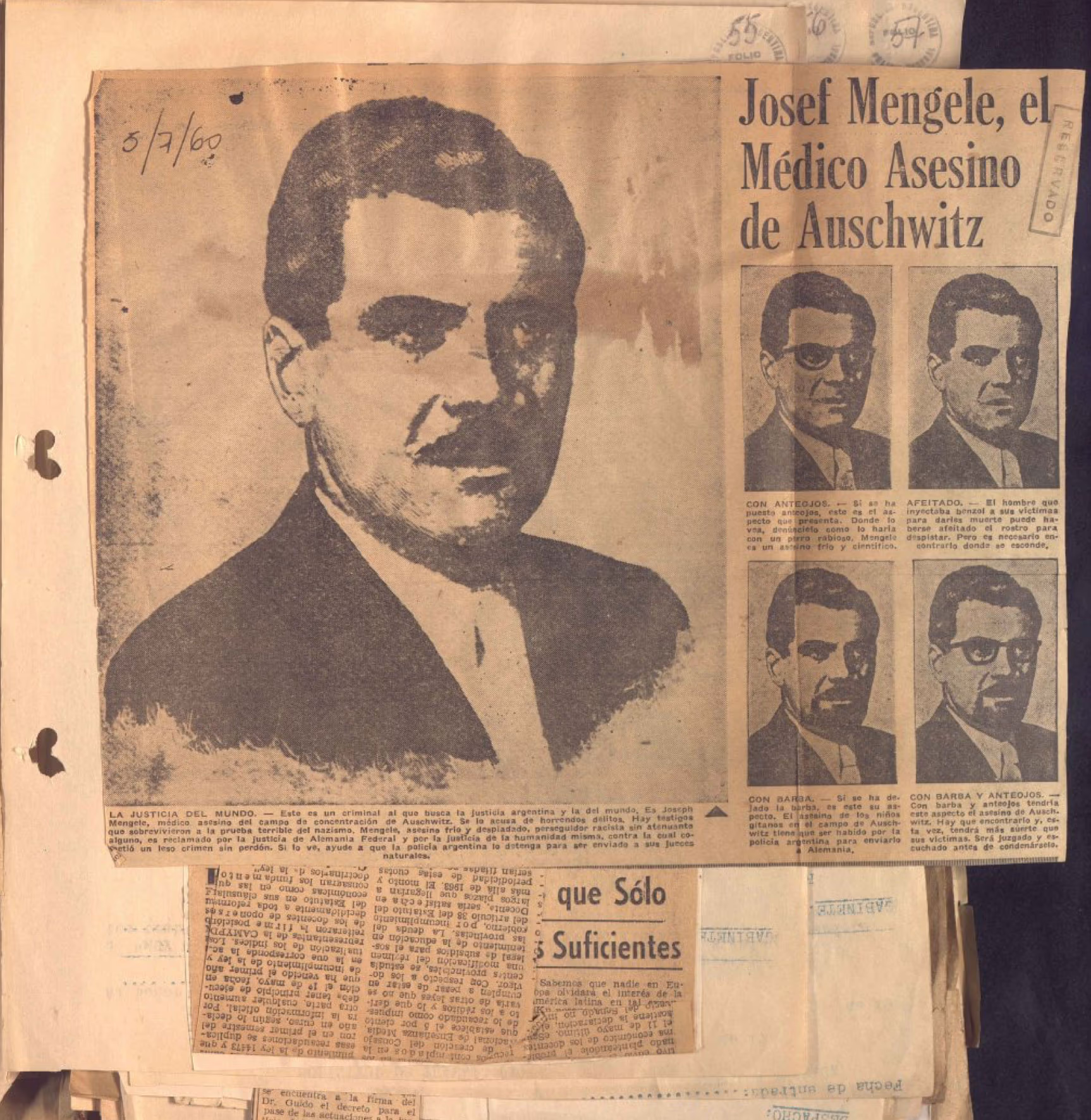

Walter Kutschmann.

Walter Kutschmann, a Gestapo officer and commander of an Einsatzgruppe involved in mass killings of Jews in Poland and Western Ukraine, hid in Argentina under a false identity. Thanks to efforts by Simon Wiesenthal, German authorities secured an extradition warrant, but Kutschmann managed to escape. He was eventually arrested in 1985, but died before he could be transferred to West Germany.

Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo chief in Lyon known as the "Butcher of Lyon," collaborated with U.S. intelligence after the war and later settled in Bolivia under the name Klaus Altmann. He was extradited to France only in the 1980s. In 1987, he was sentenced to life in prison for crimes against humanity and died in prison in 1991.

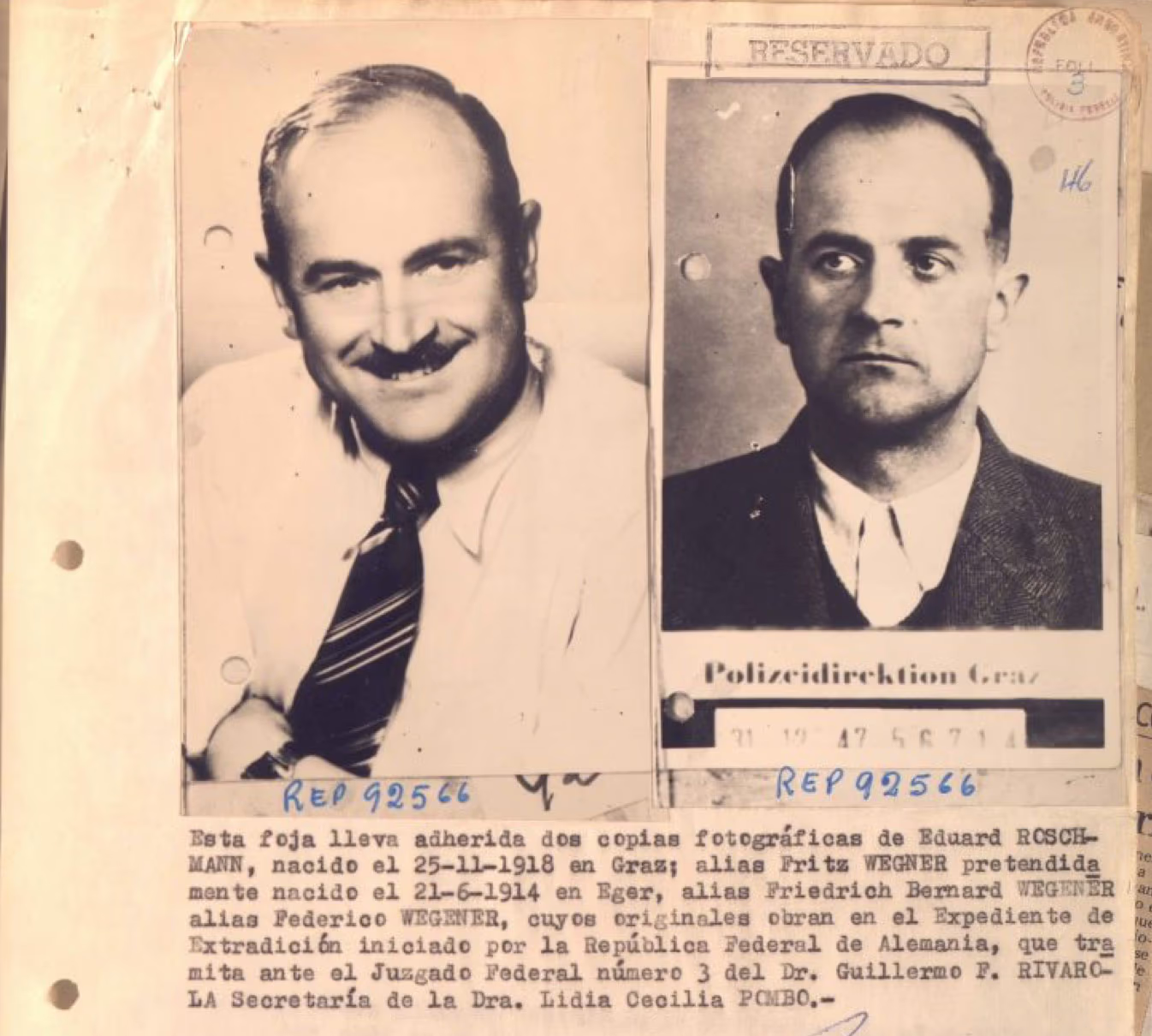

Eduard Roschmann.

Eduard Roschmann, former commandant of the Riga Ghetto, arrived in Argentina in 1948. There, he obtained citizenship under the name Federico Wegener. When Germany sought his extradition, he fled to Paraguay, where he died in 1977 without ever facing trial.

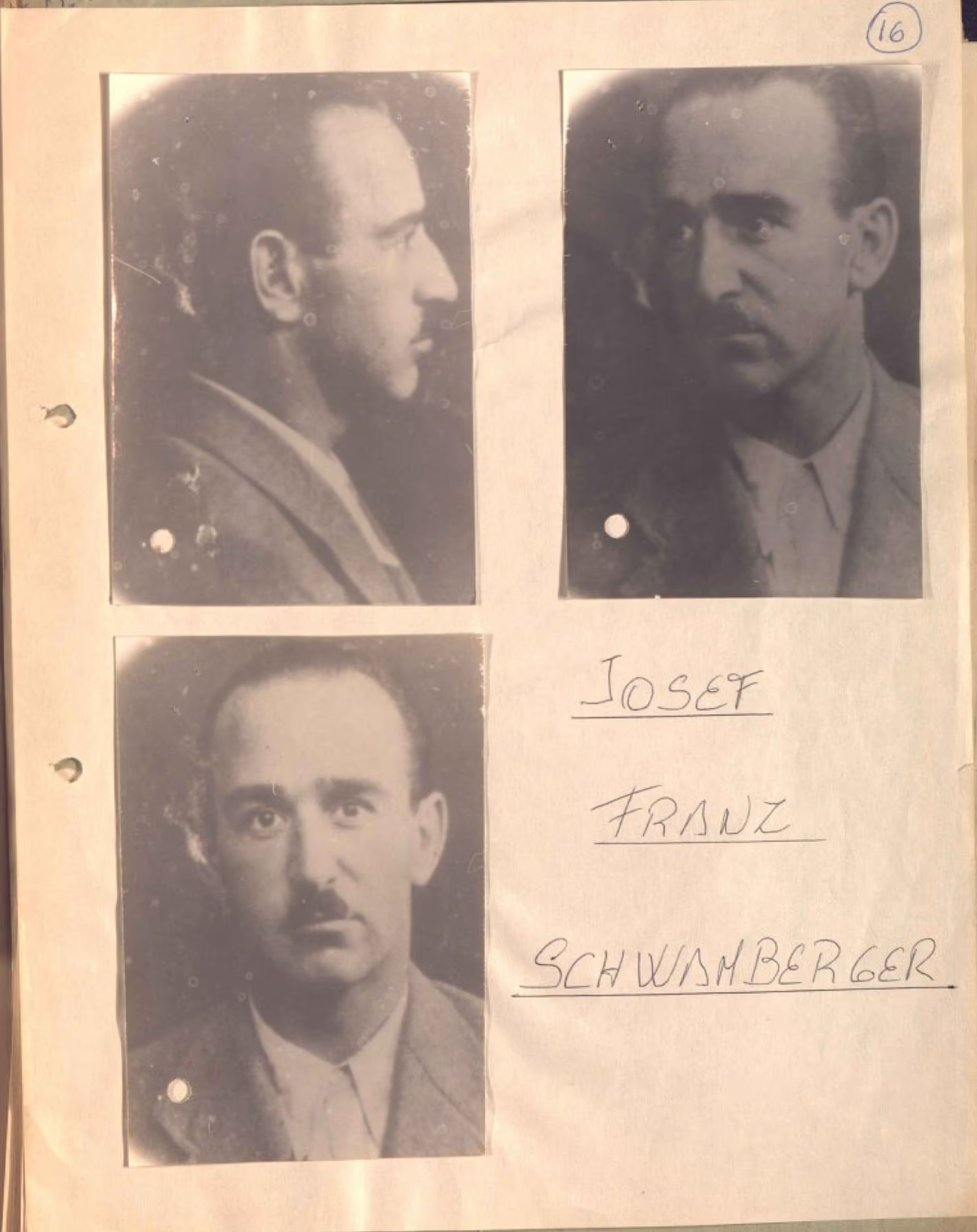

Josef Schwammberger.

Josef Schwammberger, commandant of several concentration camps in Poland, had been living in Argentina since the 1950s. Although extradition was requested in the 1970s, he was not actually handed over until 1990. In Germany, he was sentenced to life in prison and died in custody in 2004.

Ante Pavelić, leader of the pro-Nazi Independent State of Croatia, arrived in Argentina in 1948 posing as a priest. There, he founded an anti-communist movement, but fled to Chile and later Spain after an extradition request. He died in 1959.

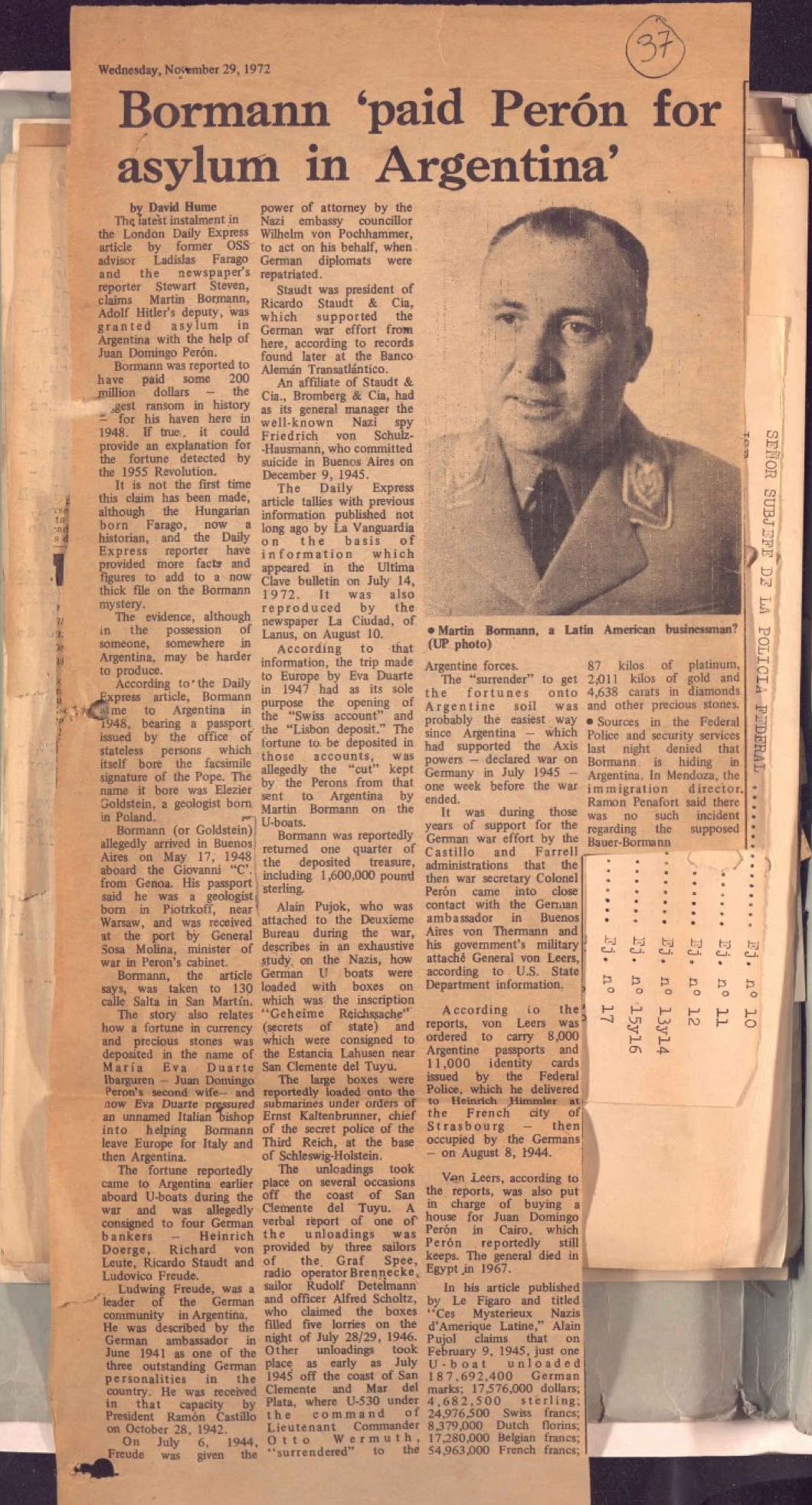

The documents also contain references to Martin Bormann, Hitler’s closest aide, who, according to the official account, died in Berlin in 1945. However, rumors of his escape to South America circulated for decades in the media and among intelligence agencies. The Argentine archives record numerous attempts to investigate these claims but ultimately conclude that no evidence of his presence in the region was found.

Martin Bormann.

The significance of the archive lies not only in the biographies it reveals. It offers insight into how Argentine authorities perceived these individuals—whether as threats, as assets, or as something best left unnoticed. During the Perón years, fugitives could be useful: the regime had an interest in German military officers, engineers, and specialists. After 1955, Argentina entered an era of instability, military coups, and institutional erosion. Even when someone within the bureaucracy knew something, that knowledge was rarely passed on.

Mengele—one of the most notorious criminals of the Nazi era—lived in the country openly under his own name. No one sought his extradition until pressure came from abroad. The same was true for Eichmann: intelligence services may have known, but chose silence. Israel’s operation provoked a diplomatic outcry, yet deep within Argentina’s bureaucratic machinery, it may well have been quietly welcomed.

Only in 1983, with the return to democracy, did Argentina begin to systematically cooperate with international investigations, fulfill extradition requests, and open its archives. The 1992 declassification marked the first step. The current publication is an act of closure—or at least a reminder: Nazi crimes do not disappear if left unnamed. They dissolve into institutional amnesia.

Echoes of War

"Too Many Remained Silent and Looked Away"

BMW, Bayer, Volkswagen, Siemens and 45 of Germany’s Largest Companies Acknowledge Responsibility for Hitler’s Rise to Power

The War Being Fought Again

World War II no longer belongs to the past. It has once again become a battleground—not for territory, but for the right to define the truth. For Russia, it is the last legitimizing myth. For Ukraine, it is a space to assert the freedom to be itself