The global economy is approaching a crossroads few dare to speak of openly. Over the past two decades, governments, corporations, and individuals have accumulated an unprecedented level of debt—more than $300 trillion. At the same time, the very nature of debt has changed: from a tool for development, it has become a condition for survival. Many countries now exist merely to service interest payments, borrowing ever more—without a clear plan for repayment.

Rising interest rates, geopolitical shifts, and climate shocks are only intensifying the strain. Countries in the Global South are already facing defaults, while developed economies are experiencing a sharp increase in borrowing costs. A financial system built on endless debt rollover is beginning to lose its stability. The question is no longer if the bill will come due—but who will be the first to run out of means to pay it.

In July 2022, a crowd of protesters stormed the official residence of Sri Lanka’s president in the streets of Colombo. The formal trigger was a fuel shortage; the underlying cause—was the island nation’s first sovereign default in history. The debt pyramid collapsed, leaving the country without foreign currency and—more crucially—without the trust of its creditors.

Protesters at an anti-government demonstration near the presidential residence in Colombo on July 9, 2022. Gotabaya Rajapaksa had left his official residence before the protest began, which was demanding his resignation.

The story of Sri Lanka quickly faded from the headlines, but it served as a warning: in a world where total debt has surpassed $300 trillion, a similar collapse could occur in several corners of the globe.

Debt problems in "peripheral" countries were once seen as isolated flare-ups. Today, the interconnectedness of markets is such that a single major default could trigger margin calls, capital flight, and a chain reaction across the derivative "fog" where trillions in obligations remain hidden.

In 2023, Sri Lanka, Ghana, and Zambia officially stopped servicing their external debt. Pakistan is teetering on the brink. In Latin America, the pattern is familiar: Argentina is negotiating its tenth debt restructuring with the IMF, while Ecuador is slashing social spending to appease creditors.

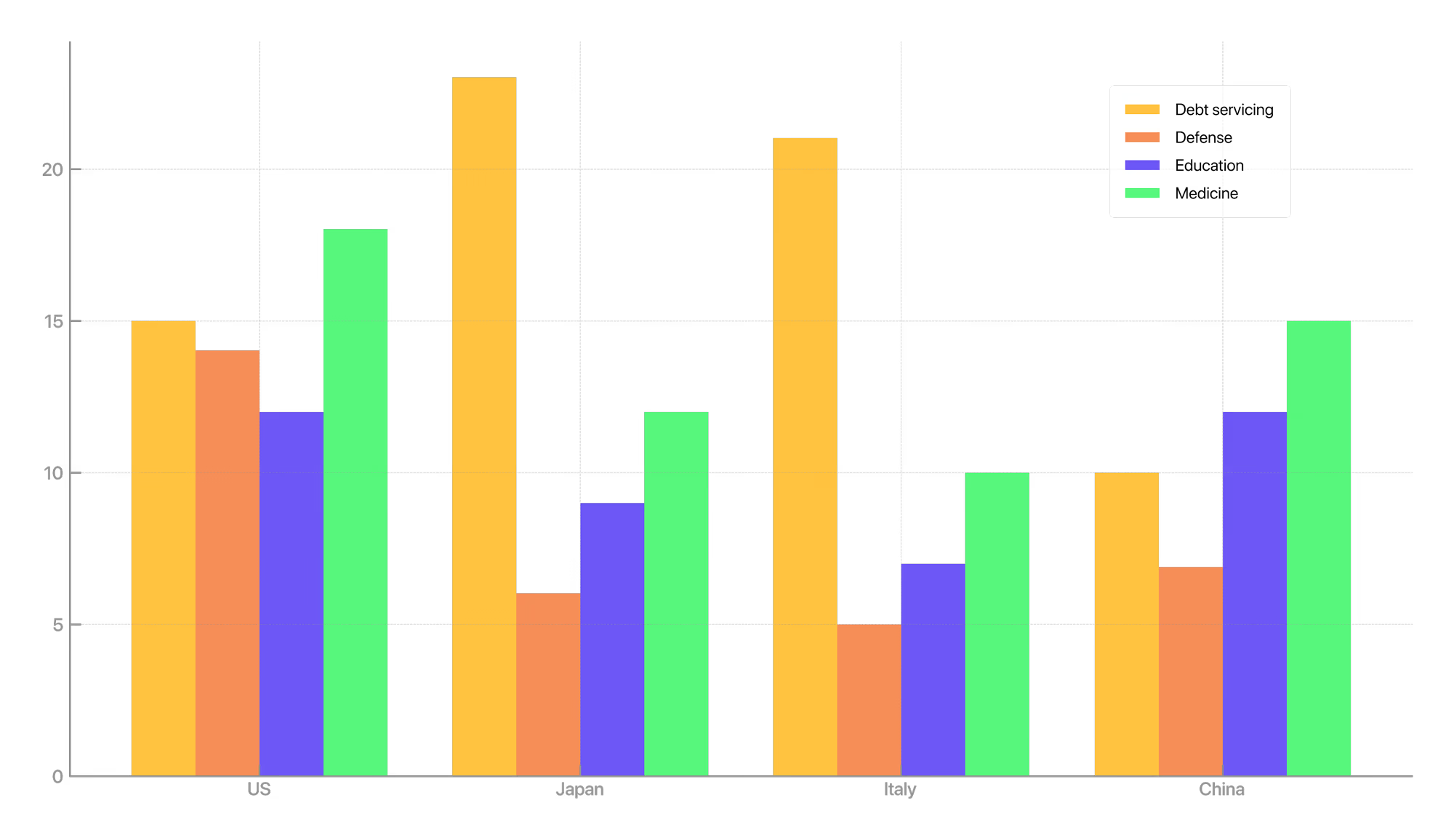

The new phase of the debt marathon is more dangerous because it threatens to engulf major economies. In Italy, the yield on 10-year bonds stands at around 3.6%—twice as high as two years ago. In Japan, debt servicing cost ¥27 trillion, or 21% of total government spending. In the United States, where total debt has surpassed $36 trillion, political battles over raising the debt ceiling continue—another crisis is expected in early 2025. In China, IMF estimates put total public and quasi-public debt at over 300% of GDP, while servicing regional debt burdens local budgets, forcing cuts in investment programs and stalling growth.

Budget Spending Structure in Selected Countries in 2024, % of Budget

Over the past two decades, the global economy operated under near-zero interest rates. Money became the cheapest resource—cheaper than labor, energy, or time. It seemed the reckoning could be postponed indefinitely, as long as the interest was paid.

Governments borrowed to fund growth. Households—to live ahead of their means. Corporations—to buy back their own shares and show growth on paper. It wasn’t a conspiracy, but rather a near-universal understanding: "Just a little longer, and things will improve."

In the past, debt crises struck one country at a time. Argentina, Greece, Thailand—each had its own collapse, and there was always an external savior. Today, the chain is so tightly linked that one weak link can pull down the rest. The key difference: the world’s largest economies are themselves overloaded with debt.

In Pakistan, where import-driven inflation has reached 30%, pharmacy owners have begun selling antibiotics by the pill—no one buys whole boxes anymore. In public hospitals, doctors switch off air conditioning to save electricity. Officials continue negotiations with the IMF, but the phrase is increasingly common: "We’re not refusing to pay—we simply can’t."

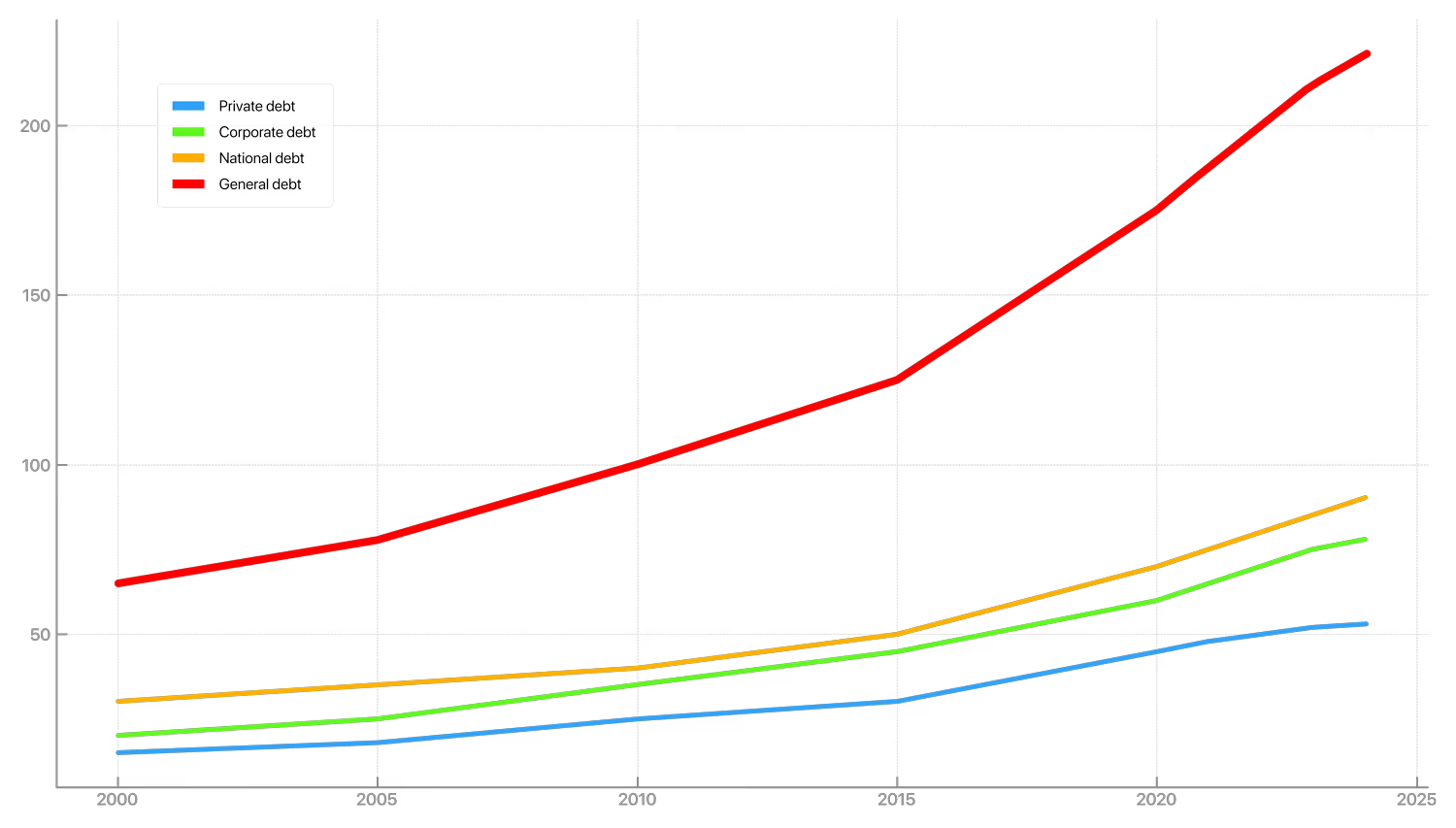

In 2024, global public debt surpassed $100 trillion, reaching 93% of global GDP. It is projected to hit 100% by 2030.

Global Debt Growth, USD Trillions

For a long time, China remained an exception—not only was it not a debtor in the usual sense, it also seemed like an anchor of global stability. But behind this façade lay a different reality: hidden debt burdens of provincial governments, the collapse of real estate giants, and asset bubbles sustained by faith in perpetual growth.

When Evergrande—the country’s second-largest real estate developer by assets—declared bankruptcy in 2023, it became a symbol not just of China’s housing market crisis but of an entire model of economic growth built on infrastructure expansion. A year later, experts cautiously began to speak of a "Japanese scenario" for China—a decade of stagnation that may be difficult to escape, even with support from the central bank.

Unfinished Evergrande residential complexes on the outskirts of Nanjing — a symbol of China’s debt crisis that has shaken confidence in one of the world’s largest economies.

But a far more fundamental shift is occurring in the United States. America has long been the main beneficiary of the global debt system: it issues the world’s primary reserve currency, and the world buys its debt. Yet cracks have begun to appear in this mechanism.

In 2024, U.S. interest payments on debt surpassed defense spending. Nearly every new tax dollar now goes not to infrastructure or education, but to paying interest. Financial markets have remained calm so far, but voices on Capitol Hill are growing louder: "We are losing the ability to manage our own economy." This year's debt ceiling approval process dragged on for 42 days, accompanied by threats of a government shutdown.

Increasingly, questions are being raised that seemed fringe just five years ago. For instance: can the dollar retain its status as a global currency if America can no longer agree on how to manage its own debt?

Against this backdrop, more and more countries are choosing to hold gold instead of bonds. Central bank digital currencies are being prepared to replace the dollar in bilateral settlements. The very fact of these shifts signals the core message: the world is preparing in advance for the possibility that the current system may not hold.

As you read this, someone in Argentina is deciding which pill to buy—there’s no longer enough money for all the medication. Meanwhile, someone in Europe is buying yet another government bond without asking the obvious question: will it ever be repaid?

If the debt model stops working, the world will be left without a mechanism to finance the future. Building schools, driving green transformation, modernizing infrastructure—all of it depends on borrowing today and repaying tomorrow. But what if "tomorrow" can no longer be bought?

Perhaps we are not witnessing just another cycle of debt crisis, but the beginning of the end of the very idea of progress on credit. The future is no longer guaranteed—and that is its new price.

Countdown to Collapse

The End of Globalization as We Knew It

Economics in the Age of New Borders

The World on Wartime Terms

As Crises Deepen, Governments Abandon the Search for Solutions and Turn to Command, Control, and the Appearance of Stability

The Real Economy Is Out of Sight

Without Rethinking Data on Supply Chains, Digital Services, and Vulnerabilities, Decisions Are Made Blindly