The rapprochement between Russia and China, which began after 2014 and accelerated in the wake of the war, is now yielding mixed results. Trade is expanding, rhetoric is aligned, and the alliance projects a façade of resilience—but strategic asymmetry is deepening. Moscow is losing initiative, gradually turning into Beijing’s junior partner. The proclaimed formula of a "strategic partnership of equals" increasingly resembles a relationship of dependence, evident in the economic, military, and symbolic spheres. This imbalance may soon provoke a new wave of frustration—not toward the West, but the East.

Xi Jinping’s presence at the anniversary celebrations in Moscow served as a key symbolic moment—marking the definitive failure of the Trump administration’s efforts to split the Beijing–Moscow axis. Yet the durability of the Sino-Russian rapprochement depends more on internal dynamics than on external pressure. As in the past, any potential rupture is more likely to arise from growing tensions within the alliance than from outside interference.

Despite talk of a "no-limits friendship," the partnership rests on profound asymmetry: China is both the near-exclusive buyer of Russian raw materials and the supplier of critically needed imports. Roughly 80% of Russian exports to China consist of mineral resources, while Chinese investment in Russia remains minimal and largely stagnant. This structure resembles the extractive dependency model of the 1990s more than any vision of an equitable partnership.

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at the parade in Moscow. May 9, 2025.

Russia’s growing dependence on China is forcing it to make concessions—even at the expense of its own diplomatic agility. In its drive to challenge the Western-led order, Moscow finds itself drawn into a new unipolarity—this time with its center in Beijing rather than Washington.

Should the elite’s and public’s faith in the "pivot to the East" give way to disillusionment, the anti-Western mobilization of recent years could morph into an "Eastern resentment." In rejecting one form of dependency, Russia has quietly entered another—one that is even more asymmetrical.

The U.S. Attempt to Split the Moscow–Beijing Axis Has Failed—But the Alliance Rests on Symbols, Not Institutions

Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow for the 80th anniversary of Victory Day was more than a ceremonial reprise of diplomatic protocol—it was a calculated performance. When Putin and Xi alternately commemorate military victories in Moscow and Beijing, they are staking a claim to an alternative reading of world history—and, more broadly, an alternative global order.

The visit was underscored by a new geopolitical configuration: China is engaged in a tariff war with the United States, and Russia remains isolated after abandoning any attempt to "reset" with Washington. The Trump administration’s offer to establish partial cooperation with the Kremlin in exchange for distancing from Beijing had no effect. Tellingly, on the day of Trump’s inauguration, Xi and Putin held a video call—a gesture of solidarity in the face of renewed American pressure. While victory on the battlefield remains elusive, their appearance on Red Square projects the image of a resilient political alliance, undeterred by external strain.

The attempt to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing appeared poorly conceived. Washington’s initiatives in the energy and Arctic domains were largely declarative, failing to address the deeper rationale behind the alliance: it is rooted not only in pragmatism but in a shared ideological foundation—rejection of liberalism, affinity for statism, and a revisionist view of the international order.

As Michael McFaul and Evan Medeiros have noted, the partnership is built on aligned core strategies: suppressing dissent, consolidating state control, and seeking to reshape global power structures. These are not tactical convergences but long-term imperatives. Just as the Soviet-Chinese split in the 20th century stemmed from internal frictions, today’s alliance is likewise most vulnerable from within. According to sources cited by The Washington Post, American efforts to foment discord were discussed directly between Putin and Xi.

On the surface, the alliance appears resilient: a shared antagonism toward the United States provides cohesion. Yet it is precisely the internal asymmetries—both strategic and economic—that make it potentially fragile. Russia’s role as the junior partner may be tolerable only under continued external pressure. Should that pressure ease—or new challenges arise—tensions within the alliance are likely to intensify.

Russia–China Trade Hits Record Highs, but Growing Imbalance Undermines Moscow’s Position

In 2024, bilateral trade between Russia and China reached a record $245 billion, with China accounting for one-third of Russia’s total foreign trade—exactly the share previously held by the European Union. Yet growth has nearly plateaued, rising just 1.9% over the year. Economic convergence is nearing its limits, even as structural imbalances deepen.

Of the $129.3 billion in Russian exports to China, 78% consisted of raw mineral resources. Before the war, that share was 62% in trade with the EU. Unlike Europe, China increasingly imports these resources in their least processed form: shipments of copper concentrate surged by 71%, while exports of refined copper declined by 6%.

This is a textbook case of vertical division of labor: Russia exports raw materials, while China controls processing. The relocation of Nornickel's refining operations to China may help circumvent sanctions, but it also shifts value-added production abroad—deepening Moscow’s economic reliance.

For China, Russia represents just another trade partner, accounting for roughly 4% of total foreign commerce. For Russia, China has become a critical economic lifeline. Western sanctions have severed Moscow’s access to its former markets, leaving it with few remaining alternatives—neither buyers nor suppliers. Nearly 60% of Chinese imports consist of essential goods: industrial machinery, electronics, and transport equipment. Outside of China, these are now largely inaccessible.

The resulting asymmetry is stark: China serves both as a near-monopoly supplier and a dominant buyer. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the automotive sector. According to Autostat, Chinese brands now control 60% of Russia’s car market, having displaced not just Western firms but domestic producers as well. Even AvtoVAZ, once a symbol of Russian manufacturing, has resorted to rebadging Chinese models. This is no longer cooperation—it is structural technological dependency.

In the truck market, Chinese dominance is even more pronounced—nearly two-thirds of all sales. Sitrak has overtaken Kamaz with a 20% market share, while Kamaz’s share has dropped to 17%. Attempts at administrative intervention—such as the ban on importing Shacman trucks—are unlikely to reverse the trend. Chinese manufacturers offer cheaper, more competitive, and more diverse vehicles.

Russia is ceding control over its domestic market in exchange for access to goods and an outlet for its raw materials—a dynamic that increasingly resembles a colonial model. As Kirill Tremasov, an advisor to the Central Bank governor, warns, a potential devaluation of the yuan would only reinforce this pattern: Chinese imports would become even more affordable, while Russian manufacturers would become even more vulnerable.

Despite Record Trade, China Is Reluctant to Invest in Russia—Exposing Its Economic Vulnerability

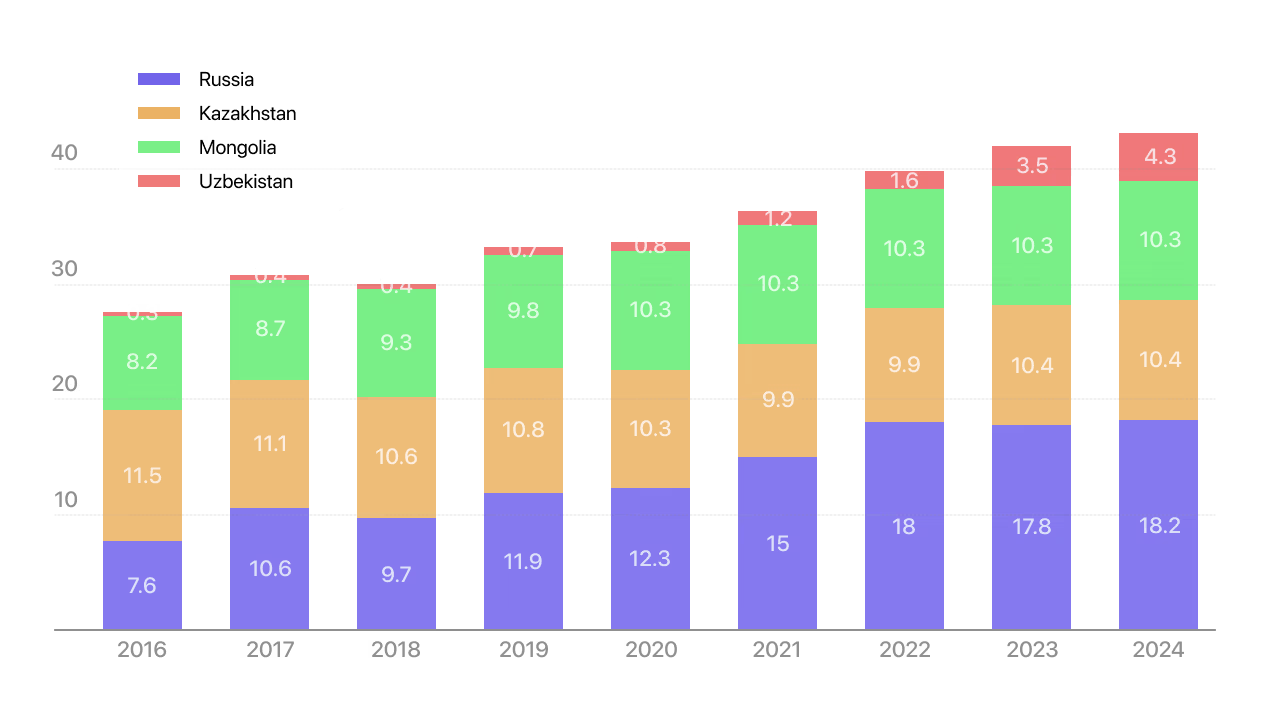

The trade boom between Russia and China is not matched by investment flows. According to data from the Eurasian Development Bank, as of mid-2024, total Chinese investment in Russia stood at just $18.2 billion—less than 1% of GDP. Nearly a quarter of that amount was tied to a single project: Yamal LNG. In all of 2023, the net increase was a symbolic $0.4 billion.

In relative terms, Russia significantly lags behind: in Kazakhstan, Chinese investment equals 4% of GDP; in Mongolia, 50%. Even Uzbekistan is becoming a priority—China’s EXEED has launched an auto assembly operation there, while similar initiatives in Russia have effectively stalled.

Dynamics of China's Cumulative Direct Investment in Eurasian Countries, 2016–2024, USD Billion

Even in the industrial sector, China remains selective: across all of Russia, there are only 14 active projects totaling $6.6 billion. Beijing avoids politically sensitive and sanction-exposed ventures, focusing instead on resource-based and infrastructure assets.

China's restraint stems not only from sanctions. It sees Russia primarily as a market, not as a target for industrial expansion. Sectoral overlaps are rare. The risk of secondary sanctions is particularly salient: even before 2022, Chinese loans were sporadic—now, the risks have become systemic.

Nevertheless, the yuan has effectively become a reserve currency within Russia’s financial system. According to the Central Bank of Russia’s 2023 report, the limited diversification options have elevated the yuan’s role in reserve management. As a result, Moscow’s macro-financial stability is increasingly tied to Beijing’s monetary policy.

There are also growing concerns about potential moves by Chinese authorities. As Bloomberg columnist Shuli Ren recalls, Beijing devalued the yuan by 10% in 2018 in response to U.S. sanctions. Today, the central bank has again allowed the exchange rate to exceed 7.2 yuan per dollar and restricted currency purchases by state-owned banks. A further devaluation could undermine the value of Russian assets denominated in yuan and erode the competitiveness of domestic producers.

In reality, the so-called "financial pivot to the East" has not resulted in capital inflows but has instead become a conduit for imported external risks. For now, these risks are offset by export revenues and budget injections—but such buffers are finite. The lack of investment is fast becoming one of the main constraints on growth.

Unlike its former relationships with Europe—where Russia moved up the value chain—the current Chinese model increasingly resembles a neo-colonial structure. Moscow gains neither technology, nor access to markets, nor genuine partnership. Only a stable hierarchy of dependence.

Central Asia, Africa, and the Balkans Are Becoming Arenas of Quiet Competition Between Moscow and Beijing

Beneath the façade of unity between Moscow and Beijing, geopolitical fault lines are becoming increasingly visible. Chief among them is Central Asia, where Russia is striving to preserve its post-imperial influence but is gradually ceding initiative to China. Moscow still maintains cultural and military clout, but its aggressive foreign policy is prompting regional elites to tilt the balance in favor of Beijing.

China operates pragmatically, without imperial rhetoric, cultivating dependence through infrastructure, logistics, and resource ties. In 2023, its trade with the region grew by 27%, reaching $89 billion—nearly half of it with Kazakhstan. In Uzbekistan, China now buys more than 80% of the country's total gas exports.

Energy infrastructure is another lever of control. Three pipelines from Turkmenistan are already operational, with construction of a fourth set to begin soon. In Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, China dominates the extractive sector, investing in mines and roads. The China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan (CKU) railway project will grant Beijing direct access to the region, bypassing Russian routes. Meanwhile, cooperation in the security sphere is also expanding—from arms deliveries to the promotion of China’s "Global Security Initiative."

This quiet rivalry extends beyond the region. In Africa, Moscow projects power through the export of chaos and paramilitary services, while China relies on infrastructure and investment. In 2023, Beijing's trade with the continent reached $295 billion, compared to Russia’s mere $24.5 billion. China is steadily filling the vacuum left by Russia’s destructive presence.

In the Balkans, China continues to expand its economic footprint through infrastructure projects, loans, and direct investments. Russia, constrained by limited resources, leans heavily on political rhetoric. But true competition is absent—Moscow simply lacks the capacity to rival Beijing under sanctions and growing international isolation.

The same pattern repeats across these regions: China deepens its presence without provoking direct conflict with Russia, yet gradually displaces it in practice. The paradox of the alliance lies here—Moscow wages a campaign against Western hegemony while surrendering ever more ground to Beijing.

Russia Is Losing Ground Even in Sectors Where It Once Held Dominance—Defense and the Arctic

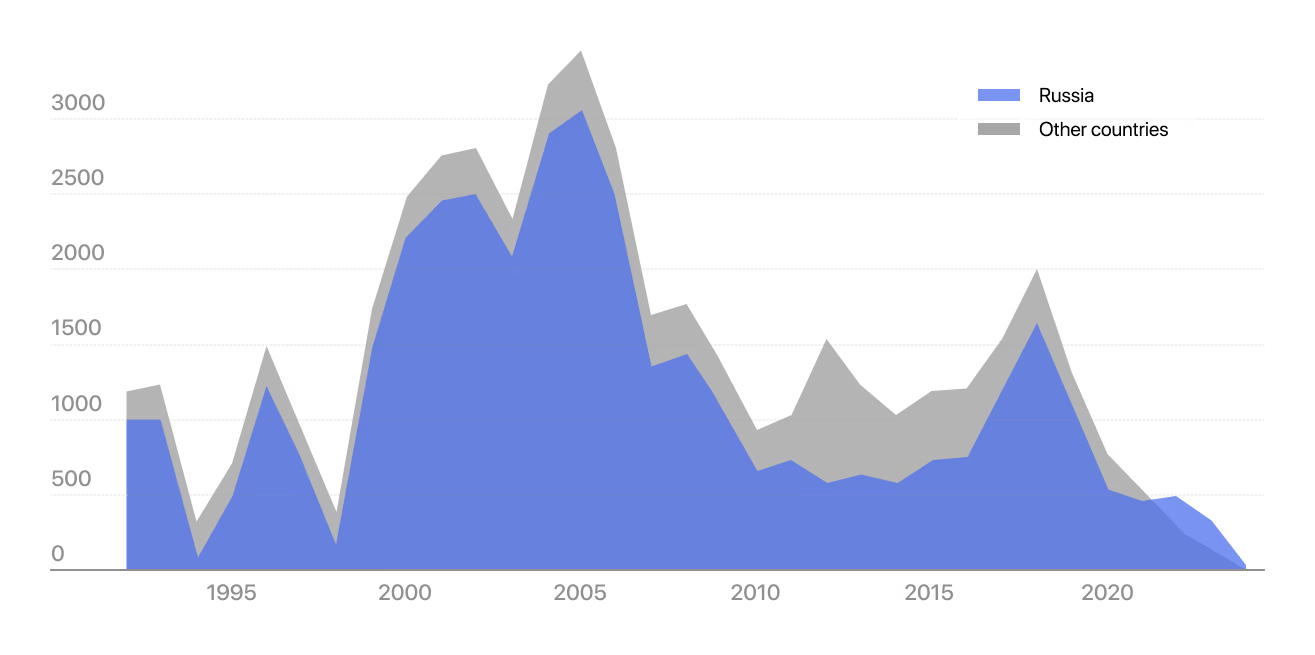

In the 2000s, Russia maintained a clear lead in military-technical cooperation: exports of fighter jets, air defense systems, and other equipment drove the modernization of China’s armed forces. But by the end of the decade, Beijing had begun cutting back purchases, ramping up its own production, and entering international markets. Moscow lost its role as a technology provider and became a niche supplier.

Attempts to reboot cooperation in the late 2010s only exposed new tensions. According to ChinaPower (CSIS), Russian officials increasingly accused China of reverse-engineering weapons. In 2019, Rostec reported around 500 cases of piracy—ranging from jet engines to Pantsir air defense systems. By then, however, Beijing had little need for Russian technology.

China's Defense Imports, 1992–2024

Since 2022, the dependency has reversed: Russia’s defense industry now relies on Chinese components, electronics, and equipment. According to SIPRI, by 2024 Russia’s share of global arms exports had dropped to 4%—down from 20% in the mid-2010s. China, meanwhile, has not only strengthened its position but, for the first time, surpassed Moscow in total arms deliveries.

Even the format of joint military drills has shifted. Initially, these exercises provided China with experience under near-combat conditions. But by the 2020s, the initiative had passed to Beijing: drills now take place on Chinese territory, using Chinese equipment and command structures. The "West. Interaction 2021" exercise marked a symbolic turning point—when the roles were reversed.

A similar shift is taking place in the Arctic. Moscow has long regarded the region as its exclusive domain—thanks to geography and military infrastructure. China, however, describes itself as a "near-Arctic state" and is pushing for international governance over the region. The Northern Sea Route, which Russia views as an internal passage, is rebranded by Beijing as part of its "Polar Silk Road" initiative.

Russia needs technology and investment to develop the Arctic, but Beijing does not view the partnership as one between equals—instead, it sees Moscow as part of its broader infrastructure orbit. This echoes a familiar pattern: Moscow yields not by choice, but out of necessity.

The Arctic remains one of the last enduring symbols of Russian great-power status, alongside its nuclear arsenal. China’s efforts to redefine this status—whether through demands for navigational freedom or conditional participation in Arctic projects—trigger deep unease in the Kremlin.

History offers a precedent: in the 1950s, the Soviet Union dominated China, only for Beijing to reject its junior status. Today, Russia faces a reversal of roles. For now, the rift is masked by diplomatic language, but the underlying dynamic increasingly points toward a clash of ambitions.

China Is Still Seen as an Ally, but the Illusion of Reciprocity Is Beginning to Erode—First in Society, Then Among Elites

Political isolation and Western sanctions have pushed Russia to turn eastward—chiefly toward China. This strategic pivot was initially accompanied by a surge of enthusiasm reminiscent of the late 1940s, when Moscow and Beijing declared an era of "eternal friendship." But as then, the rhetoric masks growing tension.

Sinophobia has deep roots in Russia. During the Soviet era, it was fueled by ideological rifts; later, it stemmed from anxiety over China’s growing presence in the Russian Far East. Only in the 2010s, amid worsening ties with the West, did China emerge as a perceived strategic pillar. According to the Levada Center, from 2006 to 2024 the share of Russians viewing China as a friendly nation rose from 20% to 65%.

But since 2023, this trend has begun to shift. Data from FOM shows a decline in positive perceptions of the partnership, with a growing number of Russians citing a deterioration in relations. The tone of focus groups has also changed: instead of framing the relationship as an "alliance," participants now describe it as "mutually beneficial cooperation"—with the benefits skewed toward Beijing. As one respondent put it: "We give them raw materials, they flood us with cheap goods"; another added, "They're milking us like a cow."

Official rhetoric remains exuberant, but within expert and elite circles, frustration and anxiety are mounting. Even among loyalists, more voices are beginning to view China’s growing power as a potential threat. A rising share of respondents now express uncertainty in surveys—a subtle yet telling indicator of growing doubt.

Once seen as an alternative to the Western model—promising industrial growth and technological breakthroughs—China is now a source of growing dependence. As stagnation sets in, the illusion of parity becomes harder to sustain. Enthusiasm gives way to realism, which may soon give way to disappointment.

The sociological dissonance is striking: Russians acknowledge that China is developing more successfully, yet believe that Russia wields greater global influence. According to FOM, 56% are convinced Moscow carries more weight internationally; the Levada Center reports that 80% of Russians consider their country a "great power," compared to just 63% who say the same about China.

Against this backdrop, a new ideological shift looms. If the "pivot to the East" begins to falter, a new external antagonist may emerge—what could be called "China resentment." This sentiment could easily replace the anti-NATO mobilization of previous years, especially if economic difficulties deepen and concessions to Beijing continue.

For the Kremlin, this poses a serious dilemma: how to maintain the official line of strategic partnership without clashing with the imperial self-image deeply embedded in Russian society and its elites. Framing the voluntary surrender of initiative as a display of strength will be a hard sell.

Allies—Almost

Russia Expands Drone Production With China’s Help

Bloomberg Documents Reveal How Chinese Technology Bypasses Sanctions to Supply the Russian Military

Russian Intelligence Warns of a Chinese Threat Amid Strategic Partnership

Behind the Rhetoric of a "No Limits" Alliance Lie Espionage, Arctic Rivalry, and Fears of Beijing’s Historic Revenge

China Is Conducting Cyberespionage Against Russia

Despite the Rhetoric of a 'No-Limits Partnership', Beijing Sees Moscow as a Vulnerable Target

Russia Loses Its Foothold in the Middle East

It Stayed Silent as Israel Struck a Strategic Partner

Made in China

China Prepares for a Prolonged Trade War

Beijing Builds Economic Resilience and Bets on Domestic Demand