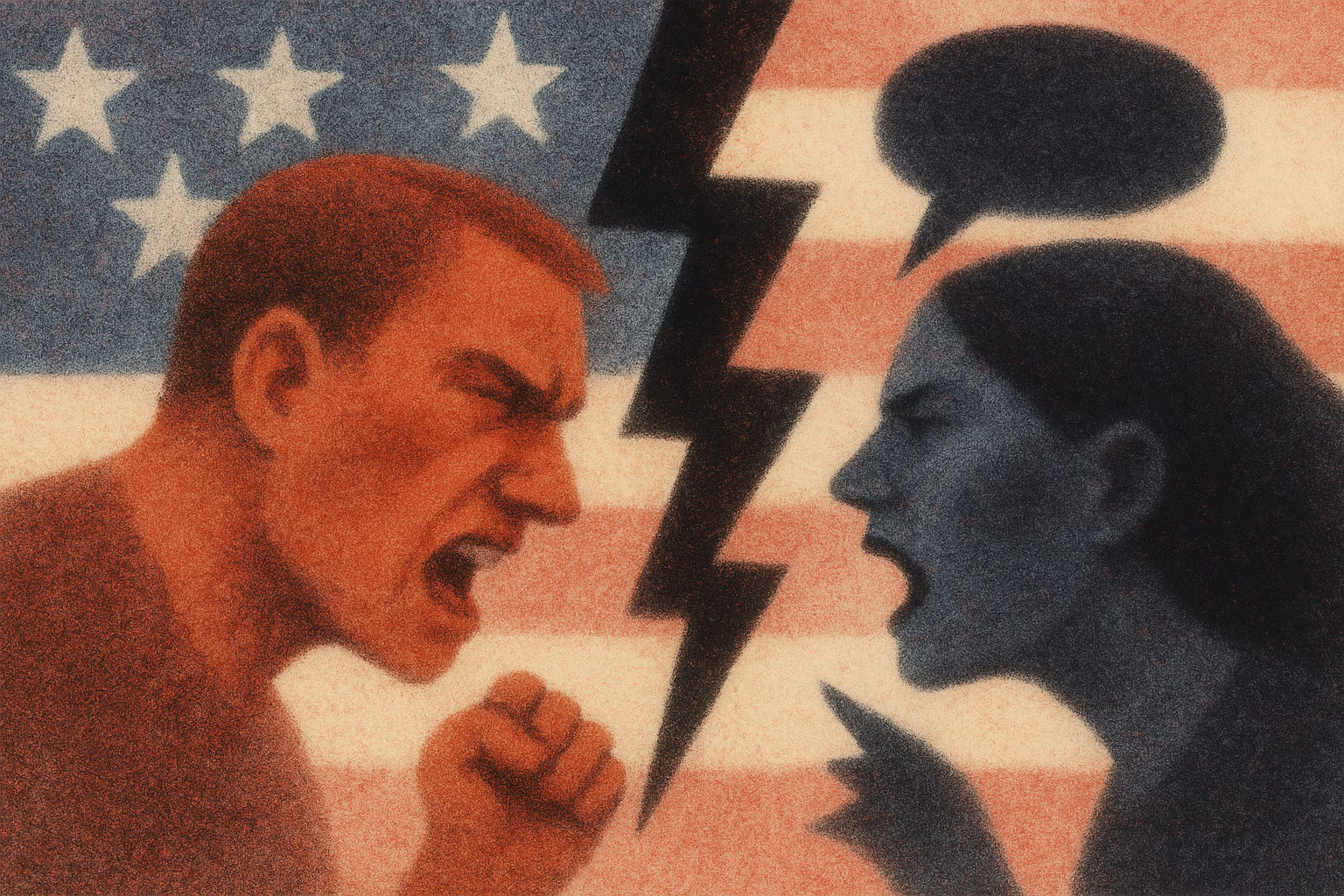

Many observers agree that the defining problem of modern America is anger. Half the country hates the other half—and the feeling is mutual. Social media creates the sensation of a mob ready to descend on anyone in its path. At times, the target is a genuinely monstrous figure—such as the ruthless killer Charlie Kirk. But often the trigger for collective outrage is far more trivial: a woman snatching a home-run ball from a ten-year-old at a Phillies game became the target of online harassment, while a man who brought both his assistant and his mistress to a Coldplay concert was exposed on the jumbotron, a revelation that ended with both losing their jobs.

This raises the question: can a state withstand such a relentless stream of hatred? Experts note that passion as an expression of emotion is not inherently dangerous. But turning outsiders into the object of impersonal abuse has a corrosive effect. The paradox is that most of those who hurl insults and curses online would never dare say the same to someone’s face—in real life they would be held accountable for their words. In the digital space, anonymity creates the illusion of impunity: one can spew filth and invective while hiding behind screen names. Some commentators argue that this radical misuse of open hostility erodes the norms of social interaction.

For politicians, anger has long since become part of the strategy. In private conversation, Donald Trump can be charming and witty, but his public career has been built on endless conflicts—with the press, universities, lawyers, big cities, Democrats, judges, prosecutors, allies and adversaries worldwide. These battles are fueled by a sense of grievance that he cultivates in his public statements. A glance at his posts on Truth Social makes clear that anger is the driving force of his activity. Journalists who followed Trump back in the 1980s in New York recall that even then he deliberately sought out conflicts—such as with businesswoman Leona Helmsley—knowing that scandal would bring him more attention. Today, it is disdain for those who stand in his way that propels the former president into the activity he has displayed in recent months.

Problems with managing emotions are hardly unique to him. Elon Musk once claimed that the Democratic Party is "the party of murder." Democrats, too, are no strangers to aggression. Congressman Adam Schiff, speaking this week, shouted at Kash Patel: "You want Americans to believe that? Do you think they are idiots?" In another exchange, the FBI director lashed out at a senator: "You are the biggest fraud ever to sit in the United States Senate, a disgrace to this institution and an absolute coward." In the echo-chamber environment, where the audience hears only itself, aggression becomes the norm: to break through on cable shows, podcasts or X feeds, one has to be even sharper than the predecessors. The system rewards outrage—genuine or performed—because it guarantees attention.

Technology companies only reinforce this cycle. In Silicon Valley, executives acknowledge that outrage drives the engagement on which the social media economy depends. Algorithms curate feeds to sustain attention, and the most aggressive remarks invariably generate the strongest reactions.

American political history shows that not all presidents built their careers on anger. Joe Biden in his public speeches cast himself as a conciliator, Barack Obama placed his bet on the "audacity of hope," and Bill Clinton played the role of a moderate Southerner who set himself against the "brainless" politics of both parties. To find a Democrat who consciously wielded aggression as a tool, one must look back to Lyndon Johnson. His style in the Senate was ruthless, and his cynical quips became part of political folklore: he said he "had Hubert’s balls in his pocket," or that he "wanted him to kiss my ass in Macy’s window at high noon and tell me it smells like roses."

Particularly repugnant after the killing of Charlie Kirk were the reactions of those who went on social media to celebrate his death. Among them were professors, journalists and others who later lost their jobs. No one forced them to post such things, and they did not know Kirk personally. But employers wanted nothing to do with people who treated someone else’s tragedy as a cause for joy. For the victim’s family—his wife and children left without a father—it was an added blow.

Commentators describe such episodes as symptomatic of an era in which collective anger has become the norm. In the public mind, they evoke the famous scene from the film "Network," where Peter Finch’s character shouts on live television: "I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore." Today that line resonates as a symbol of an age in which America is captive to its own rage.