While governments debate climate targets and companies pledge a "green" transition, one of the most ambitious technological breakthroughs of the 21st century—artificial intelligence—poses a new environmental challenge. Demand for computing power is growing rapidly, along with the energy consumption required to run data centers. But AI is not only a source of emissions—it's also a potential tool for reducing them. The question is whether governments and corporations can harness this power for the planet’s benefit—or end up accelerating its overheating.

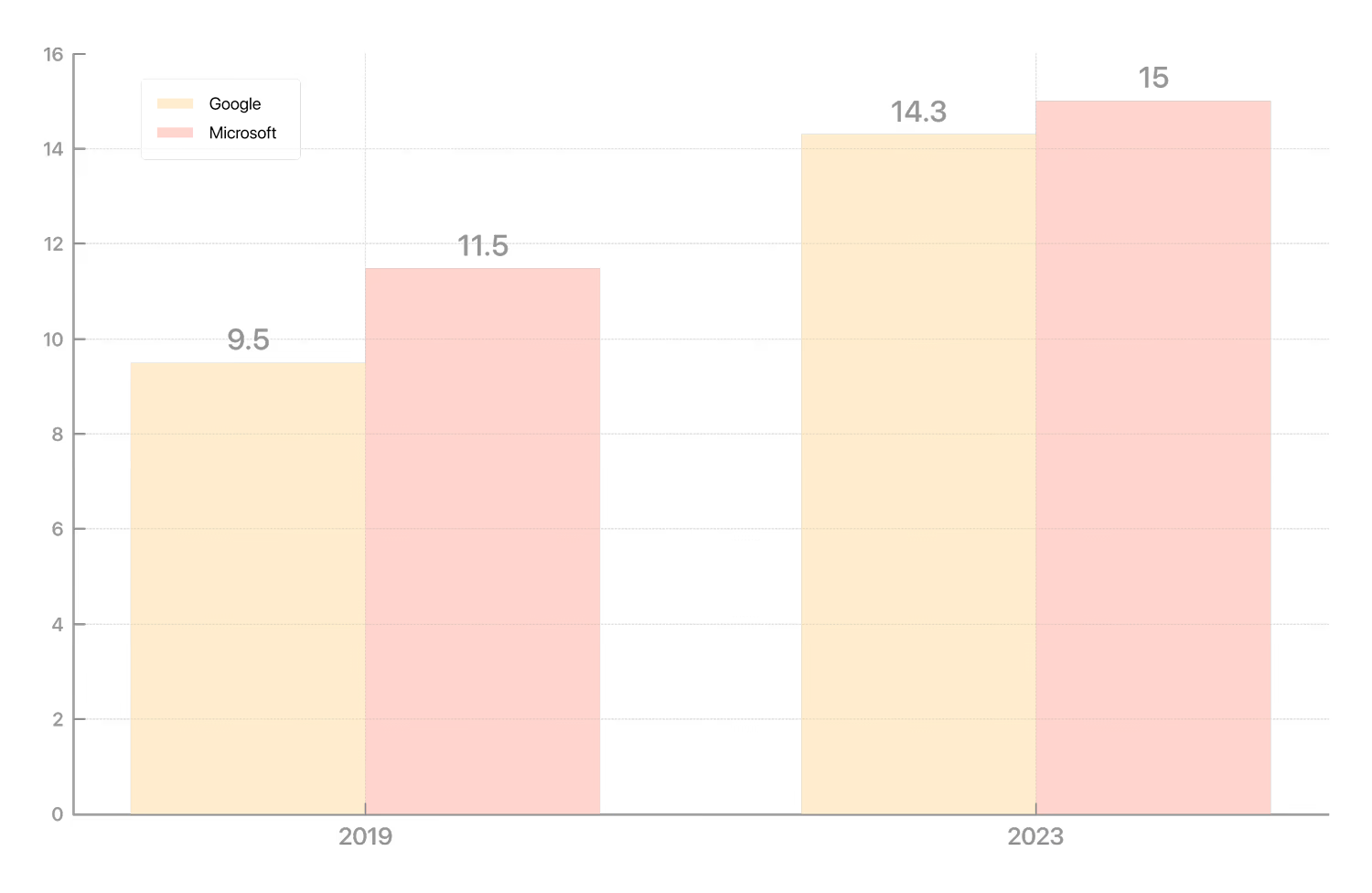

Even if you're not worried that artificial intelligence will wipe out humanity, you might still be concerned about its growing appetite for electricity—and the resulting environmental impact. A single query to ChatGPT consumes about ten times more energy than a typical search engine request, and that’s just for generating a response. Training large AI models requires vastly more resources—thousands of specialized chips may run nonstop for weeks, consuming enormous amounts of electricity. Between 2019 and 2023, Google's annual greenhouse gas emissions rose by nearly 50% (to ~14.3 million tons of CO₂), while Microsoft’s emissions rose by almost 30% since 2020. A major part of this increase stems from the energy demands of new AI-focused data centers and emissions from manufacturing the necessary hardware. With massive investments in expanding server capacity, growth is likely to continue. Still, these fears may be overstated. In absolute terms, AI may not be as energy-hungry as it seems. In fact, it could help reduce emissions in sectors that have long been the hardest to decarbonize.

CO₂ Emissions Growth at Google and Microsoft, Million Tons

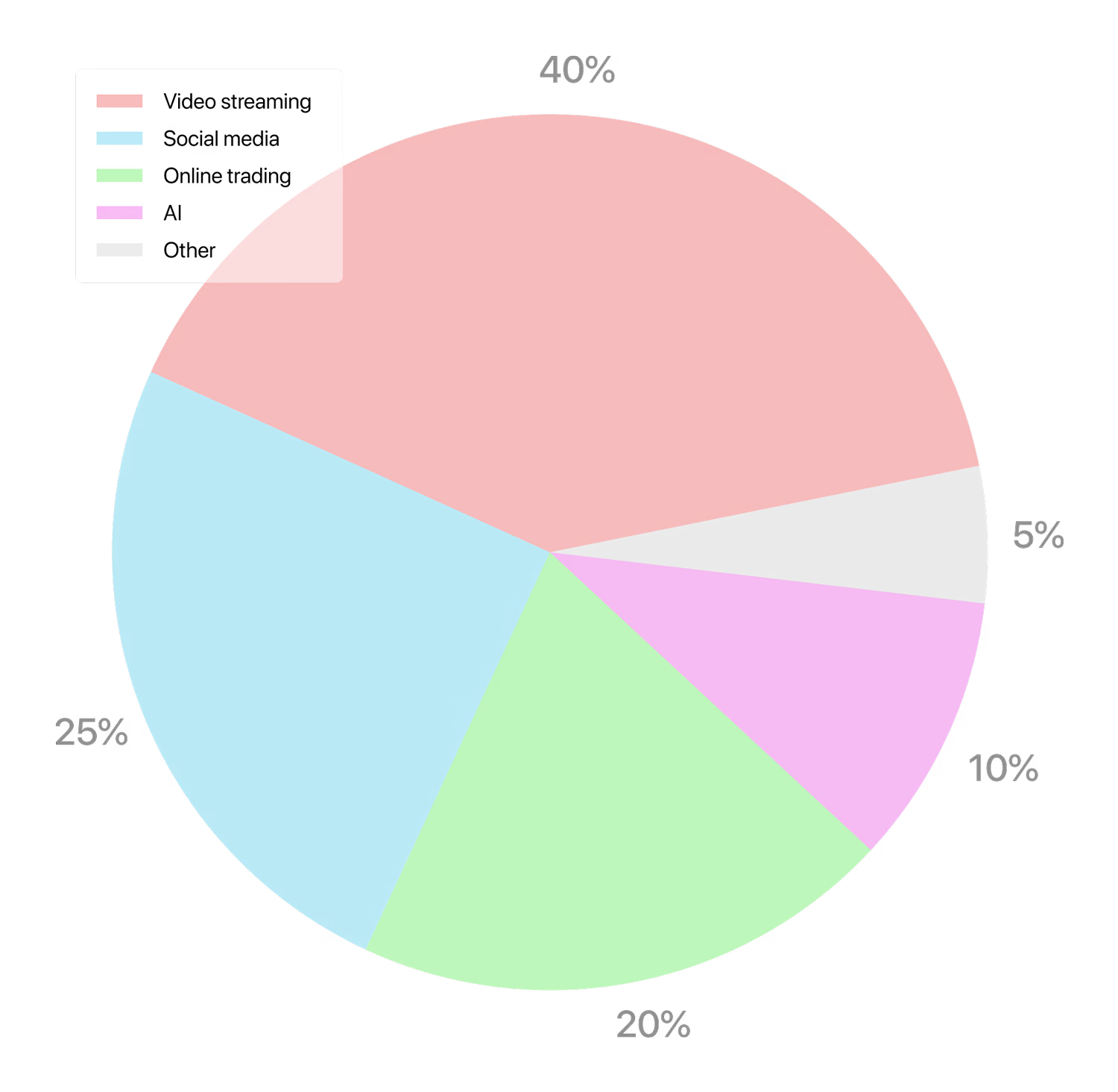

To begin with, it's worth assessing the scale of AI’s energy consumption. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), by 2026 the total electricity use by data centers could double to around 1,000 TWh per year—comparable to Japan’s annual electricity consumption. Even if the growth turns out to be that rapid (and some forecasts suggest a tripling), the current baseline is still relatively low: data centers today account for about 2% of global electricity use—and the vast majority of that energy is not consumed by AI, but by video streaming, social media, and online retail.

What Data Centers Spend Energy On

In addition, part of the electricity consumed by AI is used to "green" the economy. As we detail in the "Science and Technology" section of this issue, artificial intelligence excels at identifying complex patterns, processing large datasets, and optimizing systems—all of which help reduce emissions. AI is already improving grid efficiency, optimizing energy use in industry and transport (e.g. reducing fuel consumption in shipping), and detecting methane leaks—one of the most dangerous greenhouse gases, which might otherwise go unnoticed.

Governments and businesses face a dual challenge: to maximize the benefits of artificial intelligence while minimizing its climate impact. The most elegant solution would be to introduce a fair price on carbon emissions and let the market regulate itself. But since a global carbon tax remains a distant prospect, more realistic measures deserve attention.

The first is transparency. Today, determining the exact energy consumption of AI models is extremely difficult, as developers rarely disclose such data. In the EU, however, starting in 2026, developers of large-scale AI systems will be required to report in detail on the energy use of their models. This approach should be expanded to other jurisdictions.

The second measure is to rethink how data centers operate. According to the IEA, redistributing computational loads across locations and time zones can reduce consumption peaks and ease pressure on energy systems. More flexible data centers also better adapt to the variability of renewable sources like solar and wind. Major tech companies are already beginning to implement these ideas: in 2023, Google tested a system that delays non-urgent processing and shifts it to times and places with more green energy and lower grid loads.

Third, tech giants should live up to their own climate commitments. Major IT firms are racing to declare ambitious goals. Microsoft promises to become carbon-negative by 2030; Google aims to achieve zero operational emissions and run its data centers entirely on carbon-free energy by the same year. Amazon plans to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040 (under the Climate Pledge initiative) and has already reported 100% renewable electricity use in its operations. Meta (which owns Facebook) declared its operations carbon-neutral in 2020 and aims to eliminate all remaining emissions across its supply chain by 2030.

But declarations alone are not enough. Many corporations still rely on offset mechanisms. Amazon, for example, like others, purchases renewable energy certificates to formally compensate for "dirty" electricity use in one location by funding clean generation elsewhere. These tools have their role, but they are vulnerable: such schemes often rely on "creative accounting," and the logic of offsets is sometimes questionable—in many cases, the renewable energy they fund would have been generated anyway.

A far more effective approach is to leverage these companies' market power to accelerate the decarbonization of power systems. The largest tech firms are already among the biggest buyers of clean electricity—for instance, in the U.S. they sign long-term contracts with independent renewable energy producers. But they could go further: by investing in the construction of new green capacity, pushing for zoning and permitting reforms to remove obstacles to clean energy deployment, and supporting alternatives such as geothermal and nuclear power.

If they double down on this path, AI could shift from a climate threat to a climate solution.

The Heat Ahead

'Climate Realism'

A World Three Degrees Warmer—and Colder in Blood

Melting Glaciers Threaten Large-Scale Consequences for the Planet

Why Can’t the World Afford to Lose Its Ice?

Why Cloud Brightening Projects Face Public Pushback?

Climate Engineering Meant to Slow Global Warming Is Being Stalled Not by Technology—But by Mistrust From Local Communities

Less Ice, More Flowers

Antarctica is Warming Rapidly