This week, the UK will host a Dragons’ Den-style event where tech companies will have 20 minutes each to pitch their ideas for automating the justice system. It is just one of many examples of how the cash-strapped Labour government is turning to artificial intelligence and data analytics to cut costs and boost the efficiency of public services.

Amid mounting criticism—including accusations that Downing Street is "hooked on AI like sugary drinks"—the Department of Health has announced the launch of an AI-powered early warning system to detect problems in maternity wards. The move follows a string of high-profile scandals in maternity care. Health Secretary Wes Streeting has also stated he wants one in eight surgeries to involve robotic assistance within the next decade.

Artificial intelligence is already being used to sort through the 25,000 inquiries received daily by the UK’s Department for Work and Pensions, as well as to identify potential cases of fraud and errors in benefits claims. Ministers have even been given a dedicated AI tool for what is known as "mood assessment" in Parliament—designed to help them better understand the political risks associated with various initiatives.

Time and again, the government is turning to technology to address acute crises that in the past would have been met with more staff or more funding.

The digitization drive—personally overseen by Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Science and Technology Secretary Peter Kyle—has brought the government into direct partnership with major US tech companies. Last month, Google, Microsoft, Palantir, IBM, and Amazon took part in a Ministry of Justice roundtable. But the UK is far from alone. From Singapore to Estonia, more and more countries are embedding AI into their public service systems.

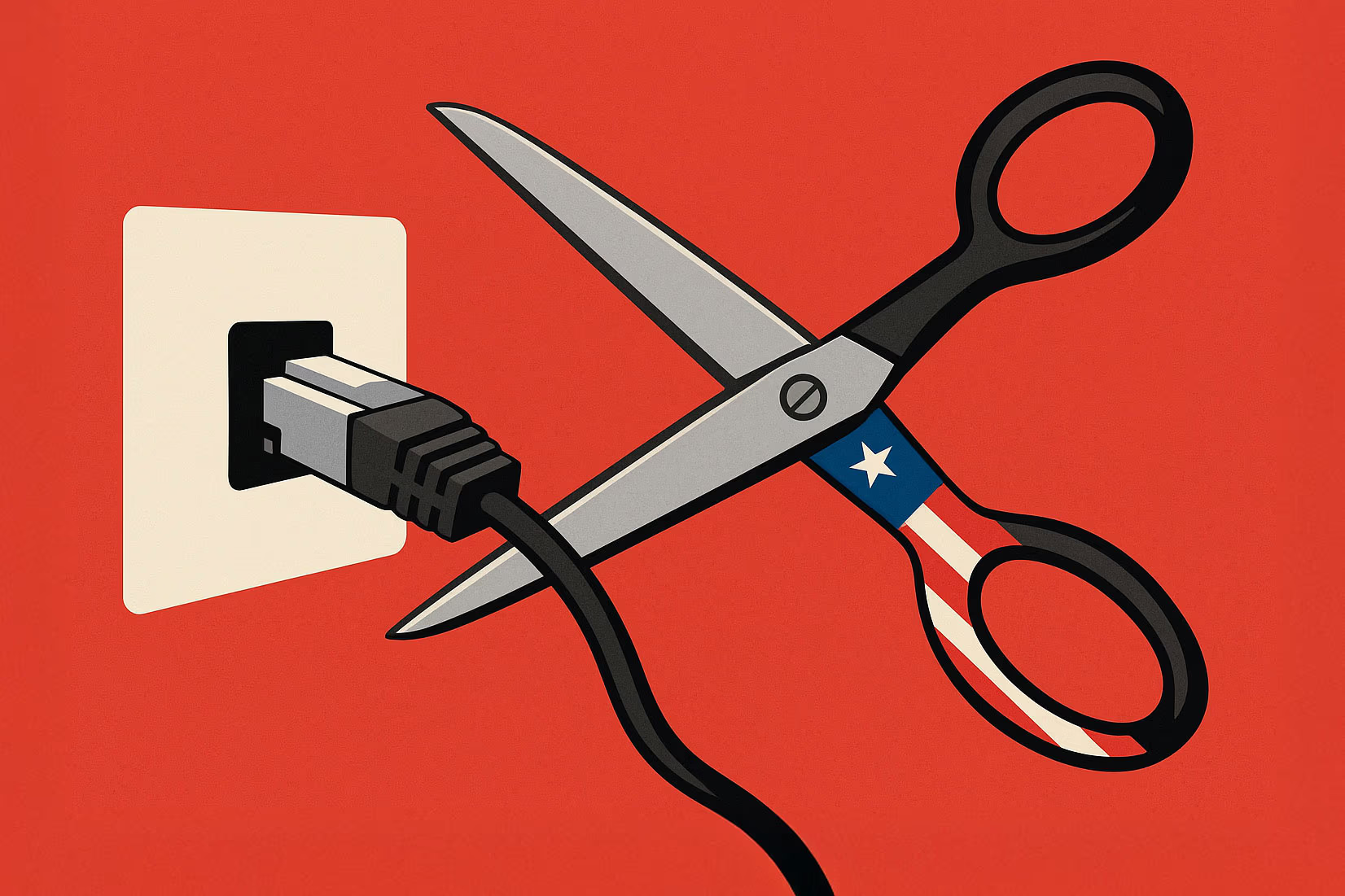

Digital Sovereignty, Outsourced

UK and EU Government Data to Be Moved Into Google and Microsoft Clouds

The Step Opens Access for U.S. Authorities, Deepens Reliance on Single Providers, and Undermines Digital Sovereignty

Politico: Europe Fears the U.S. Could Cut Off Its Internet

The Threat No Longer Feels Hypothetical

Jigar Kakkad, director at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change—which advocates for an expanded role of technology and is partly funded by tech firms—put it this way: "Our system is broken. It can no longer cope with demand. There are two options: keep pouring money into the old model and make up for labor shortages with immigration—or use technology."

"I believe the answer is technology. But it’s crucial that we set the terms: systems must be designed by people and governed by clear rules."

Kyle has recently been especially vocal in stressing that the government is doing everything it can to make major tech companies feel confident about operating in the UK. Speaking at London Tech Week, he told business leaders that the country’s regulatory and urban planning policies are being shaped to make things as easy as possible for them: "It all adds up to a picture of a government that is on your side."

The question of integrating technology into public services forces ministers to choose between developing solutions in-house or purchasing them from private companies. The temptation is strong—to award contracts to outside providers in order to achieve maximum impact as quickly as possible. For tech firms, billions are at stake: according to the research group Tussell, the value of digital contracts in the UK public sector reached £19.6 billion in 2023, up from £14.4 billion in 2019.

But introducing AI and automation into public services is far more sensitive than, say, helping drivers navigate or recommending songs on a playlist. People turn to the state at their most vulnerable—making any errors especially damaging.

A recent study by the Ada Lovelace Institute found that 59% of respondents expressed concern about the use of AI to assess eligibility for welfare benefits. By comparison, only 39% were worried about facial recognition in policing.

Public trust in the motives of private tech firms is also eroding. According to the same survey, people are significantly less likely to trust private contractors than government bodies when it comes to developing AI systems for welfare or cancer diagnostics. Even so, government institutions rank behind academia and non-profits in public confidence.

The institute has called on MPs to launch an inquiry into how companies and their affiliated entities shape media and political discourse around the benefits of AI in the public sector—and how effective current safeguards are in preventing conflicts of interest and the "revolving door" between government and the tech industry.

"When AI is presented as a catch-all solution to the challenges of public administration, society begins to ask: whose interests are driving these proposals? Citizens expect transparency and a system in which AI in public services serves the people—not profit," the institute’s statement read.

AI Profile

If AI Lets Us Do More in Less Time—Why Not Shorten the Workweek?

Companies Introduce AI With the Threat of Layoffs

But That Strategy Risks Undermining Trust and Demotivating Staff