Every week, the world inches closer to creating an artificial superintelligence. Today’s AI systems can already write reports, prepare presentations, and generate videos—tasks that not long ago required skilled professionals. The problem of "hallucinations" is becoming less pressing. Unsurprisingly, more and more people are asking: will humans be left without work?

In early 2024, search queries like "AI unemployment" hit record highs. And in cities like London and San Francisco, the question "How much time do you have left?" is increasingly heard—even in casual conversations. But is AI really pushing humans out of the labor market?

A common belief is that AI is already reducing the number of jobs. One frequently cited example is a study by Carl Benedikt Frey and Pedro Llanos-Paredes of Oxford, which links automation to declining demand for translators. Yet U.S. labor data tells a different story: over the past year, employment in the translation sector has actually risen by 7%.

Another often mentioned case is the fintech company Klarna, which announced it was shifting its customer support to AI. But just a few months later, its messaging had shifted. CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski recently stated: "If you want to, a human will always be available."

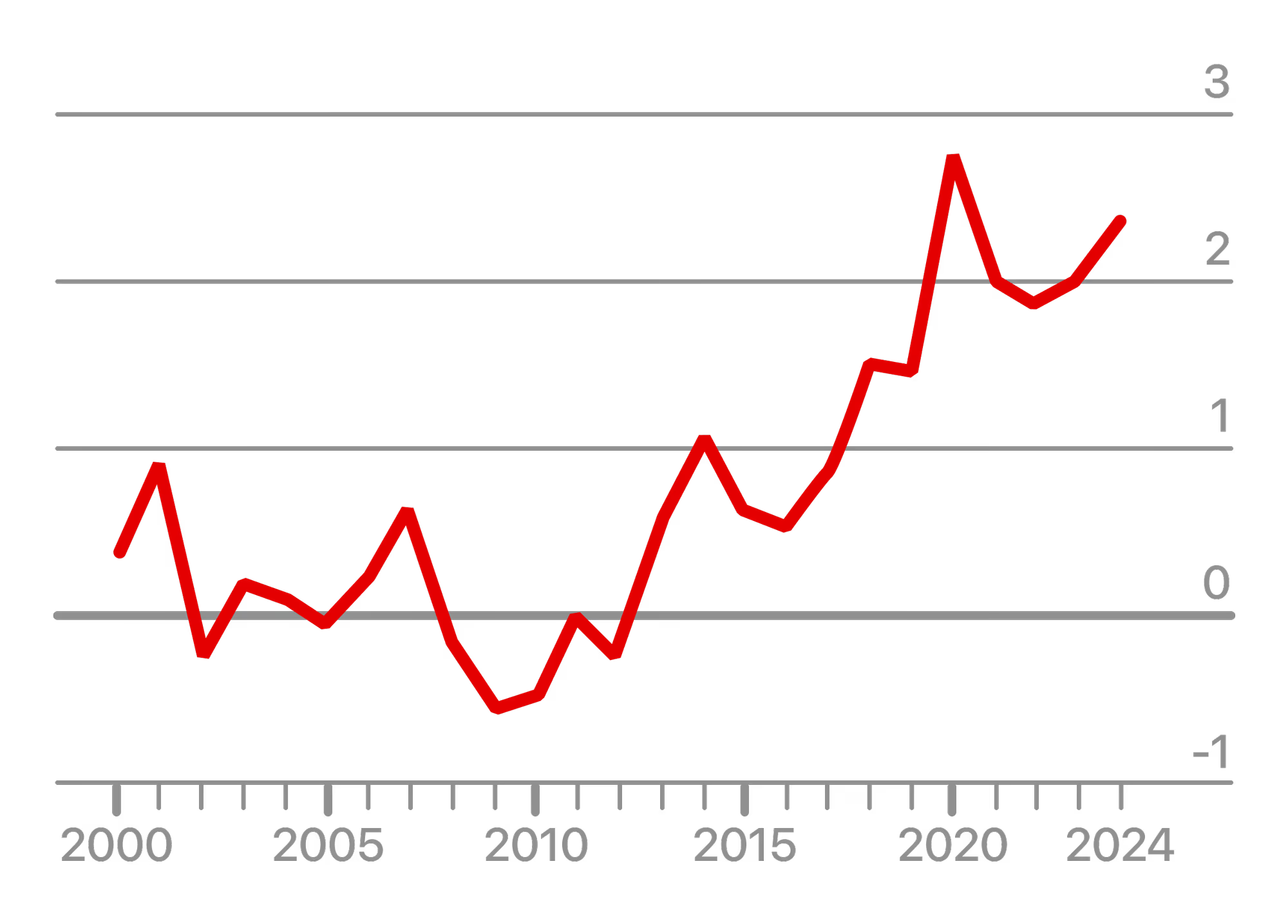

Some analysts are searching for signs of automation in macroeconomic trends. One focal point is the gap between unemployment rates among recent college graduates and the national average. Today, young professionals are more likely to be out of work than the U.S. workforce as a whole.

Unemployment Gap Between U.S. Bachelor's Degree Holders Aged 20–24 and the National Average, %

The explanation seems intuitive: graduates often begin their careers in white-collar roles—as paralegals, junior analysts, or presentation designers. These are precisely the kinds of tasks AI is already capable of handling. Could these positions be the first casualties of automation?

Yet the data doesn’t support this alarming narrative. The rise in relative unemployment among graduates began back in 2009—well before the emergence of generative AI. And the absolute unemployment rate in this group remains low, around 4%.

When analyzing U.S. employment by occupation, one notable category is white-collar workers—those in back-office roles, financial operations, sales, and other cognitive professions. These jobs are often labeled as especially vulnerable to automation. But once again, the data defies pessimism: over the past year, their share of total employment has actually risen slightly.

Across the economy, the U.S. unemployment rate remains low—at 4.2%. Wages continue to rise, despite ongoing talk of AI-driven job displacement. A similar trend is visible beyond the U.S.: wage growth is steady in the UK, the eurozone, and Japan. In 2024, the share of working-age people in employment across OECD countries reached a record high.

There are two main explanations for what we’re seeing. The first: despite declarations of digital transformation, the real-world deployment of AI remains limited. Official estimates suggest that fewer than 10% of U.S. companies use AI to produce goods or services.

The second explanation is that even when AI is adopted, it doesn’t necessarily lead to layoffs. The technology may accelerate workflows and boost efficiency, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for human involvement. Instead of job cuts, companies are seeing gains in productivity.

So far, there is no compelling evidence that AI is displacing human workers on a large scale. Contrary to the popular narrative of alarm, the data tells a different story: jobs are holding steady, wages are rising, and technological breakthroughs are not triggering immediate labor market destruction.

AI Profile

The Limits of Control

OpenAI and the Visionary Who Can Neither Be Held Back nor Replaced

If AI Lets Us Do More in Less Time—Why Not Shorten the Workweek?

Ideology at the Top, Infrastructure at the Bottom

While Washington Talks About AI’s Bright Future, Its Builders Demand Power, Land, and Privileges Right Now

AI’s Carbon Conundrum

The technology that could save the planet might also help burn it