Today, speaking live on the TSN program on the 1+1 channel, EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas said that “a very quick path to peace is not in Ukraine’s interest.”

Her statement came at a moment when international politics is debating a new settlement proposal promoted by people close to Donald Trump. The set of ideas already made public implies painful compromises for Kyiv—from freezing the front line to ceding partial territorial control in exchange for external security guarantees.

For Ukraine, this is far from an abstract debate. After nearly four years of war, the country’s starting position in any talks has objectively worsened: the military is depleted, the economy is propped up by loans, and humanitarian pressure is rising. As a result, any claim that “a quick peace is not beneficial” inevitably draws close scrutiny—especially when voiced by partners who have avoided the most difficult decisions themselves.

Europe Has Repeatedly Slowed Attempts at Settlement

In 2022, Ukraine and Russia approached the Istanbul framework, then considered the closest to a preliminary agreement. In 2023, options for a ceasefire through intermediaries were discussed, and in the autumn of the same year the United States quietly tested the possibility of “freezing” the front line. In early 2024, Western diplomacy again circulated ideas for a limited settlement. Each time, European capitals took a critical stance, fearing that an overly rapid process would lead to peace on Moscow’s terms.

In all these instances, European governments expressed caution. Their official arguments remained consistent: the risk of an imposed peace, the consolidation of occupation, and a strategic pause for Russia. Yet such caution contrasts with the fact that the European Union, at the same time, avoided steps that could have strengthened Ukraine’s position in any negotiating process.

EU Financial Flows Worked in Moscow’s Favor

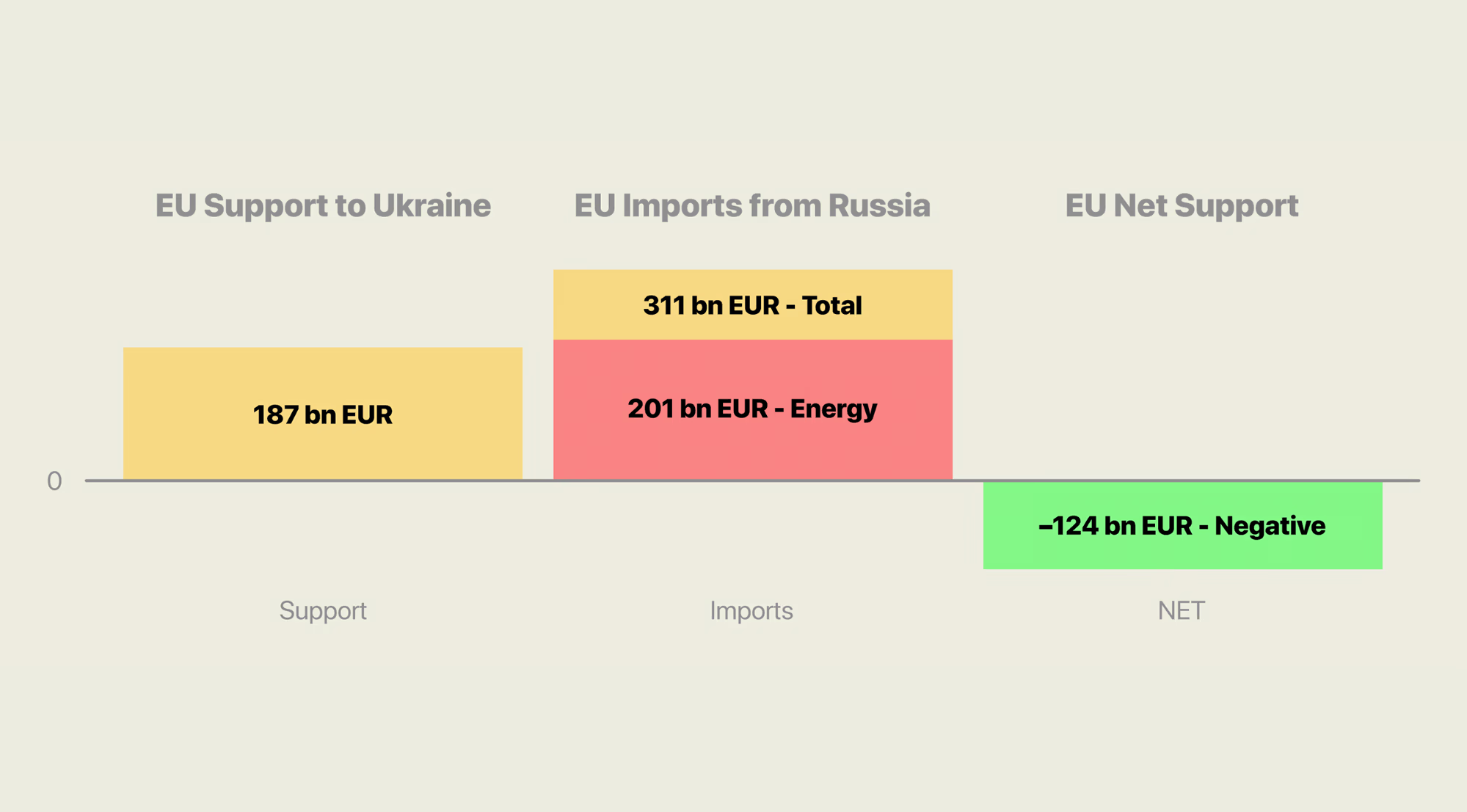

Sweden’s foreign minister, Maria Malmer Stenergard, recently presented data that reshapes the understanding of Europe’s wartime policy.

Since February 2022, EU countries have transferred €311 billion to Russia in exchange for goods and energy imports.

Over the same period, Ukraine received €187 billion in assistance. The difference—€124 billion in Moscow’s favor.

These figures show that the European economy remained a significant source of revenue for Russia’s budget—even as Brussels’ rhetoric grew tougher. On paper, Europe backed Kyiv; in practice, it continued to supply a substantial share of Russia’s export earnings.

During the War, Russia Has Received €124 Billion More From the EU Than Ukraine

Infographic

Starmer Vows to Eliminate Russian Oil and Gas from Global Markets

Leaders of the U.S., U.K., and Ukraine Step Up Pressure on Putin After Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil

The Gas Issue Remains Unresolved

Despite reduced pipeline deliveries, Europe continues to purchase Russian gas—including through LNG shipments, mixed cargoes and intermediary schemes. This does not violate EU regulations, but it preserves financial channels that play a direct role in sustaining Russia’s economy.

Direct pipeline volumes have fallen, but LNG purchases have increased, including through intermediaries and mixed cargoes. This has allowed Moscow to retain part of its export revenue while enabling Europe to avoid a sharp economic shock.

In the context of the war, this creates a paradox: European states debate the “undesirability of a quick peace” while continuing to buy energy from an aggressor state.

The More Russian Gas France Buys, the Louder Its Promises Not to Let Moscow Prevail in Ukraine

Paris Remains the EU’s Largest Importer of Russian LNG Despite Calls for an Embargo

Britain Condemns Russia’s War Against Ukraine but Buys Gas From TotalEnergies, Which Exports It From Russia

Politico Found the Company Supplies the Prime Minister’s Residence and Dozens of Government Buildings

Sanctions Have Proved Less Effective Than Expected

Over the course of the war, the EU has adopted 19 sanctions packages. They restricted parts of Russia’s imports and exports but did not fundamentally alter the structure of its economy. Moscow managed to redirect trade, expand military production and strengthen parallel logistics chains through third countries.

The sanctions signaled political unity, but they did not become a tool that meaningfully reduced Russia’s ability to wage war—and therefore did not strengthen Ukraine’s negotiating position.

Corruption in Ukraine Is a Recognized Problem That the EU Prefers to Address Quietly

Several major corruption scandals surfaced in Ukraine during the war. They involved defence procurement, ministerial operations and the distribution of funds. For European donors, these episodes signal potential risks to the effectiveness of their assistance.

Yet the EU’s response has remained restrained. Brussels has avoided harsh public criticism, wary of undermining the internal stability of Ukraine’s leadership and the cohesion of the Western coalition. The calculation is politically understandable, but it weakens confidence in claims of Europe’s “strategic vision.”

Questions Deferred Since 2022 Are No Longer Off-Limits

How the Atmosphere in the Capital Has Changed—a Report From Kyiv

The Corruption Schemes That Never Stopped

How the “Mindich Tapes” Scandal Deepens Public Disillusionment in Wartime Ukraine

The core of Kaja Kallas’s position is a warning against a settlement that would cement Russia’s territorial gains and create long-term security risks for Europe. It is a logical and understandable argument.

But the problem lies not in the logic itself, but in how consistently it aligns with the EU’s actions.

⋅ For nearly four years, Europe has avoided steps that could meaningfully shift the balance of power;

⋅ EU financial flows to Russia have exceeded the assistance provided to Ukraine;

⋅ Gas imports continue;

⋅ Sanctions have proved limited in effect;

⋅ Corruption risks in Ukraine have not prompted strict reform requirements.

⋅ EU financial flows to Russia have exceeded the assistance provided to Ukraine;

⋅ Gas imports continue;

⋅ Sanctions have proved limited in effect;

⋅ Corruption risks in Ukraine have not prompted strict reform requirements.

The EU consistently highlights the risks of a hasty settlement, yet for almost four years it has avoided decisions that could genuinely change conditions on the battlefield: it has not halted purchases of Russian energy, has not imposed a truly restrictive sanctions regime, and has not responded to Ukrainian corruption scandals with sufficient rigor. Against this backdrop, a simple question arises: on what basis does Europe today determine what pace of peace is “in Ukraine’s interest” when it has avoided taking many of the most difficult decisions itself?