While diplomatic efforts to reach a ceasefire in Ukraine stall, Russia is quietly expanding its military presence along its longest land border with NATO—1,340 kilometers shared with Finland, which joined the alliance in 2023 after decades of neutrality.

According to data confirmed by NATO officials and previously published reports, recent satellite imagery shows active militarization of the border regions. The images reveal rows of new tents, storage facilities likely meant for military equipment, and upgraded shelters for combat aircraft.

In Kamenka, just 60 kilometers from the Finnish border, over 130 army tents have been set up since February 2025. An area that remained undeveloped as recently as 2022 is now capable of housing up to 2,000 troops.

Around 160 kilometers to the south, in Petrozavodsk, three large hangars have been constructed—each designed to store more than fifty armored vehicles. The city is also slated to host a new army headquarters that will oversee tens of thousands of soldiers.

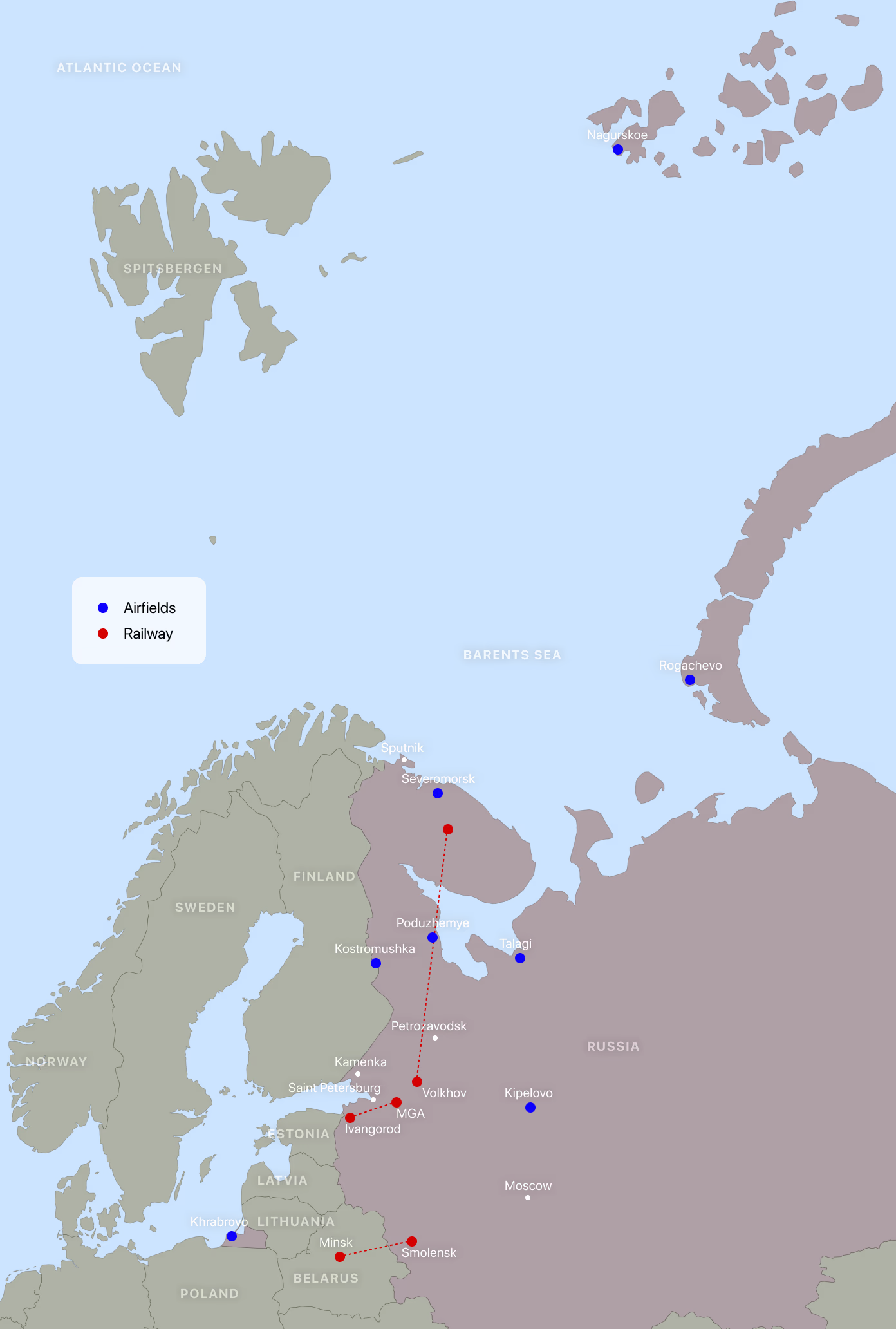

Map of Military Infrastructure in Northwestern Russia

In Kamenka, near the Finnish border, new housing for military personnel has been built. In St. Petersburg, a military hospital has been modernized. In Petrozavodsk—the administrative center of Karelia—new headquarters for an army corps and storage facilities for equipment have been established. And in the settlement of Sputnik, in the Murmansk region near the Norwegian border, a new military town is taking shape.

Finland’s NATO membership bid, submitted in 2022, prompted Moscow to announce plans to increase the size of its armed forces from one million to 1.5 million personnel and to enhance combat readiness along its western frontiers.

In the Arctic, work has resumed at the Severomorsk-2 base—a helicopter facility that was shut down in 1998 and formally reopened in 2022. Until recently, its use was minimal. According to Finnish military historian Emil Kastehelmi, who analyzed satellite imagery as part of the Black Bird Group, the base had only hosted a drone regiment, with no heavy equipment or active operations.

"Now we’re seeing vegetation being cleared, infrastructure being repaired," says Kastehelmi. "It appears that Russia is preparing the site for a much broader operational role."

In Olenya air base, also known as Olenogorsk, there haven’t been significant changes in the infrastructure. However, activity there has increased, as Russia has moved many Tu-95 strategic bombers to the field during the war to protect them from drone strikes. 8/ pic.twitter.com/uZIoN8eAwg

— Emil Kastehelmi (@emilkastehelmi) May 7, 2025

He emphasizes that this is not yet a case of large-scale militarization: "We’re observing military activity, the restoration of infrastructure, and likely preparations for new troops. But nothing truly radical—so far.

Finland officially joined NATO in April 2023, followed by Sweden a year later—a move that triggered a sharp response from Moscow. Russian authorities pledged retaliatory measures, describing the alliance’s expansion as a direct threat to national security.

"NATO expansion is an encroachment on our security and Russia’s national interests," Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said at the time. "We will closely monitor the situation in Finland and assess the extent of the threat it poses to us."

Several months later came the first response: Russia attempted to provoke a migration crisis along the Finnish border. Despite official denials, Helsinki viewed it as a coordinated operation, and in November 2023, Finland fully closed its land border with Russia. Simultaneously, authorities announced that asylum requests would now only be accepted at entry points open to air and sea traffic—that is, at ports and airports.

While the current buildup near the Finnish border is not comparable to the force concentrations seen ahead of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, analysts view it as a potential precursor—early signs of a sustained expansion of Russia’s military footprint in the north.

For Moscow, this region holds strategic value. The more than 1,000-kilometer border with Finland has become Russia’s longest direct frontier with NATO. The Kremlin sees this stretch as a key defensive buffer for St. Petersburg and the entire northwest of the country.

In a Future Conflict Between Russia and NATO, Finland Could Play a Central Role

"Now that Finland is a full-fledged member of the alliance, Russia has no choice but to take its border seriously," says Ed Arnold, senior research fellow at the UK-based Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). "If war breaks out between NATO and Russia in the Baltics, Finland will not stay on the sidelines. It would likely try to launch a counteroffensive aimed at the Kola Peninsula—home to Northern Fleet forces and part of Russia’s nuclear triad. The Finns could seriously disrupt logistics by severing the land connection between St. Petersburg and Murmansk."

Still, the question of whether the Finnish-Russian border will become a new flashpoint after the war in Ukraine remains unresolved.

"It’s hard to say right now," admits Finnish military analyst Emil Kastehelmi. "The war in Ukraine is still raging, and even achieving a temporary ceasefire is proving extremely difficult. Time will tell how extensive Russia’s investments in the region will be—bases, units, manpower. But one thing is already clear: this is a serious effort."

The militarization near Finland’s border fits into the broader context of growing geopolitical competition in the Arctic—a region rich in energy resources and crisscrossed by critical shipping routes. Amid this tension, the U.S. and Finland are holding joint exercises in May to rehearse scenarios for a full-scale conflict with Russia. And in November 2024, thousands of NATO troops participated in major artillery drills in northern Finland, near the Russian border.

For Helsinki—a city that endured Soviet invasion during World War II—Russia is not just an adversary of the past, but a potential threat to the future. Confronted with Vladimir Putin’s imperial ambitions, Finland has dramatically accelerated the modernization of its armed forces.

By 2029, the government plans to raise defense spending to 3% of GDP. At the same time, officials are considering raising the upper age limit for reservists to 65—giving Finland a potential mobilization pool of one million people by 2031, nearly one in five citizens. In early April, Prime Minister Petteri Orpo announced Finland’s withdrawal from the Ottawa Convention banning anti-personnel mines. With that move, Helsinki joined Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—countries that exited the treaty a month earlier, citing growing threats from Russia.

"The Finnish position is simple: we must be able to repel a Russian attack on our own," explains Ed Arnold of the UK-based RUSI. "That’s their starting point, and that’s how they’re building their military. In the event of war, Finland could mobilize up to 284,000 troops—more than the UK, Germany, or France. Possibly more than anyone in Europe except Poland."

According to Arnold, Finland not only has the most powerful artillery force in the European Union but also maintains substantial stockpiles of weapons and ammunition. The Finnish arsenal includes a large fleet of self-propelled artillery systems, including South Korean K9 Thunders and M270 multiple launch rocket systems—comparable to the HIMARS platforms that have inflicted significant damage on Russian forces in Ukraine.

This year, Helsinki is also beginning to receive its first fifth-generation F-35 fighter jets from the United States. The €8.4 billion contract with Lockheed Martin, signed in 2021, provides for the delivery of 64 aircraft to replace Finland’s aging F/A-18s and form the backbone of its air force. The F-35 remains the world’s most expensive and technologically advanced combat aircraft.

Finland clearly does not intend to be an easy target. "This is likely one of the best-equipped armies in Europe—not just for conventional warfare but also for countering hybrid threats," says Arnold. "It would be extremely unwise for the Russians to initiate a conflict with the Finns."

Even if, following a potential ceasefire in Ukraine, Russia were to shift significant forces to the Finnish border, NATO’s reinforced eastern flank would make such an operation extraordinarily difficult.

"This is no longer just about the Baltics—Russia now has to account for the entire Finnish border as well as the Ukrainian front, whatever shape that takes," Arnold explains. "That demands more forces, spread across a much wider area."

"Strategically, Russia made a profoundly shortsighted decision when it launched this war," he concludes.

What Are You Gonna Do About It?

Five Russian Bases Near Sweden’s Border Undergoing Upgrades

Each Could Host Nuclear Weapons

Russia Covers Its Shadow Fleet With Military Aircraft

Does Brussels Have Any Real Tools to Respond—Or Will It Once Again Resort to Rhetorical Concern?

Managed Chaos in the Black Sea

How Russia Is Using the Blockade of Ukrainian Ports as a Political Bargaining Chip