In March, the Trump administration cut funding to the University of Pennsylvania—officially for allowing transgender women to compete in women’s sports, despite a presidential decree signed by Trump on Inauguration Day, January 20. At that time, he approved a package of executive orders targeting the transgender community: trans women were banned from participating in athletic competitions, transgender individuals were barred from military service, and the legal definition of sex in the United States was reduced to a rigid binary—either male or female.

People experiencing gender dysphoria—a sense of disconnect between gender identity and the sex assigned at birth—have always existed. But only in the 20th century, with advances in medicine, did they gain the means to change their appearance to match their identity and gradually become visible in public life. In most European countries, the rights of transgender individuals are recognized and protected, yet the new stance in Washington signals a reversal—one that risks reinstating institutionalized discrimination.

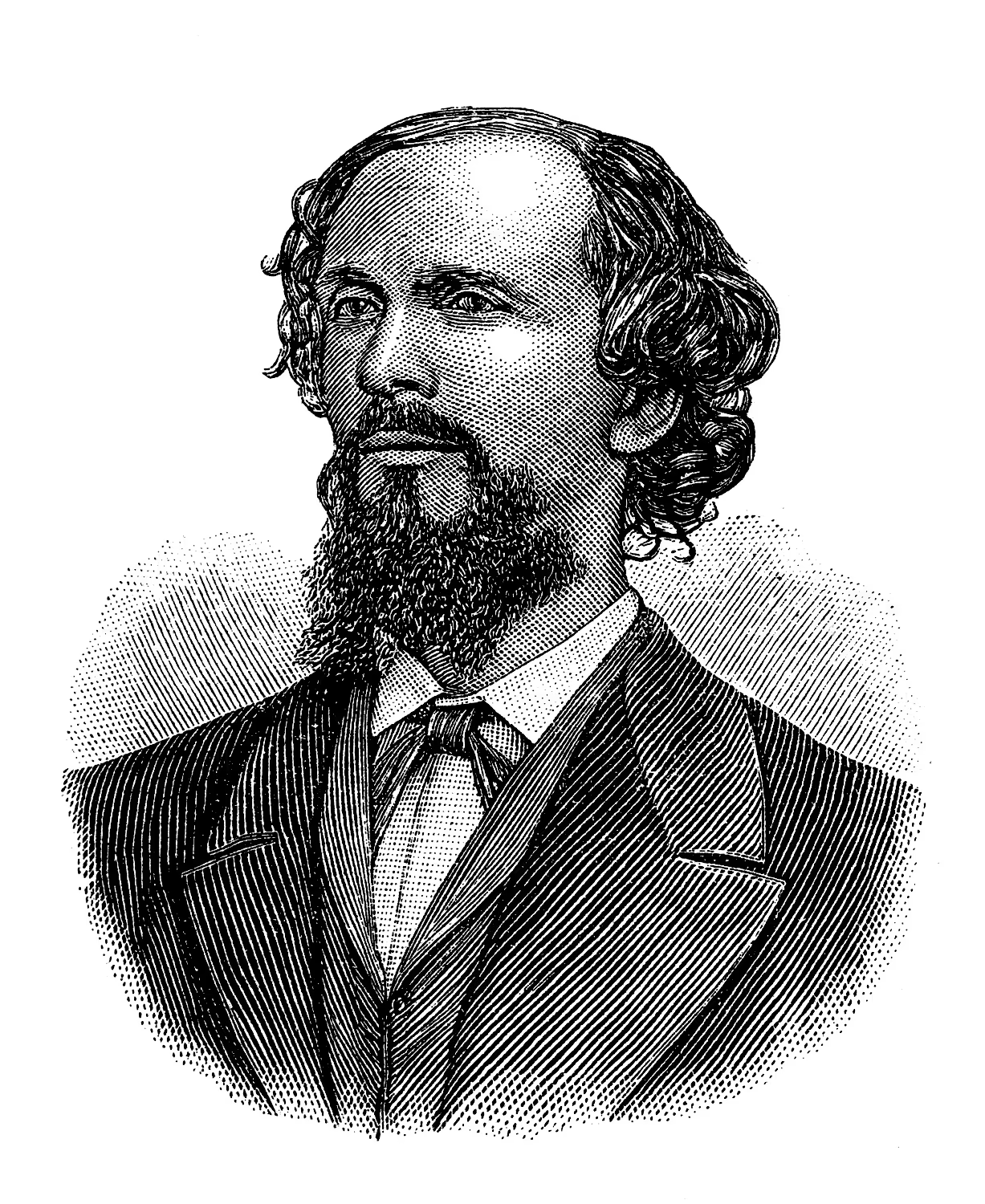

Karl Ulrichs and His Concept of "Urnings" Marked the Beginning of Scientific Inquiry Into Gender Identity and Homosexuality in the 19th Century

The 19th century marked a starting point in the struggle of transgender people for recognition—largely within the broader context of LGBT history. One of the first to attempt a scientific description of gender incongruence was German lawyer and researcher Karl Ulrichs, a pivotal figure in the emergence of sexology. He introduced the term "urning" to describe a person in a male body who, as he put it, possesses a "female soul."

In 1862, Ulrichs openly disclosed his identity to family and friends—what today would be called a coming out. He recalled feeling different from an early age: he was gentler than other boys, played only with girls, dressed in women’s clothing, and dreamed of being a girl. Over time, his interest in cross-dressing faded, but his attraction to men remained. Still, contemporaries often described his behavior as typically masculine, underscoring the complexity and ambiguity of such identities long before the emergence of modern gender terminology.

Karl Ulrichs.

In the 1860s, Karl Ulrichs traveled extensively across Prussia, continuing to develop his scientific views and publish research on what he called "uranology"—the study of attraction between people of the same sex. In conversations with others he referred to as "urnings," Ulrichs gradually expanded his theory, introducing new categories that, in modern terms, correspond to bisexuality, transgender identity, and a broader spectrum of gender and sexual identities. His works were often banned as unacceptable and radical, but he persisted in asserting: same-sex attraction is not a crime, and criminal prosecution for it must be abolished.

After Ulrichs’s death in 1895, the fight for LGBT rights was taken up by another German scholar—Magnus Hirschfeld. He was 27 at the time and was practicing medicine in Magdeburg. Many of his patients were men struggling with severe internal conflict over their homosexuality. A number of them sought his help after suicide attempts—bearing scars and other physical signs of despair. Hirschfeld made every effort to support them not only medically but also psychologically, urging them to reject fatal outcomes and accept themselves.

Magnus Hirschfeld Establishes a Scientific Center Offering Early Gender-Affirming Surgeries—Until Nazism Halts the Research

In 1897, Magnus Hirschfeld, together with a group of academic allies, founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee—the world’s first organization advocating for LGBT rights. The committee campaigned to repeal criminal penalties for same-sex relations and worked to educate the public in order to reduce prejudice and promote the recognition of homosexuality as a natural expression of human identity.

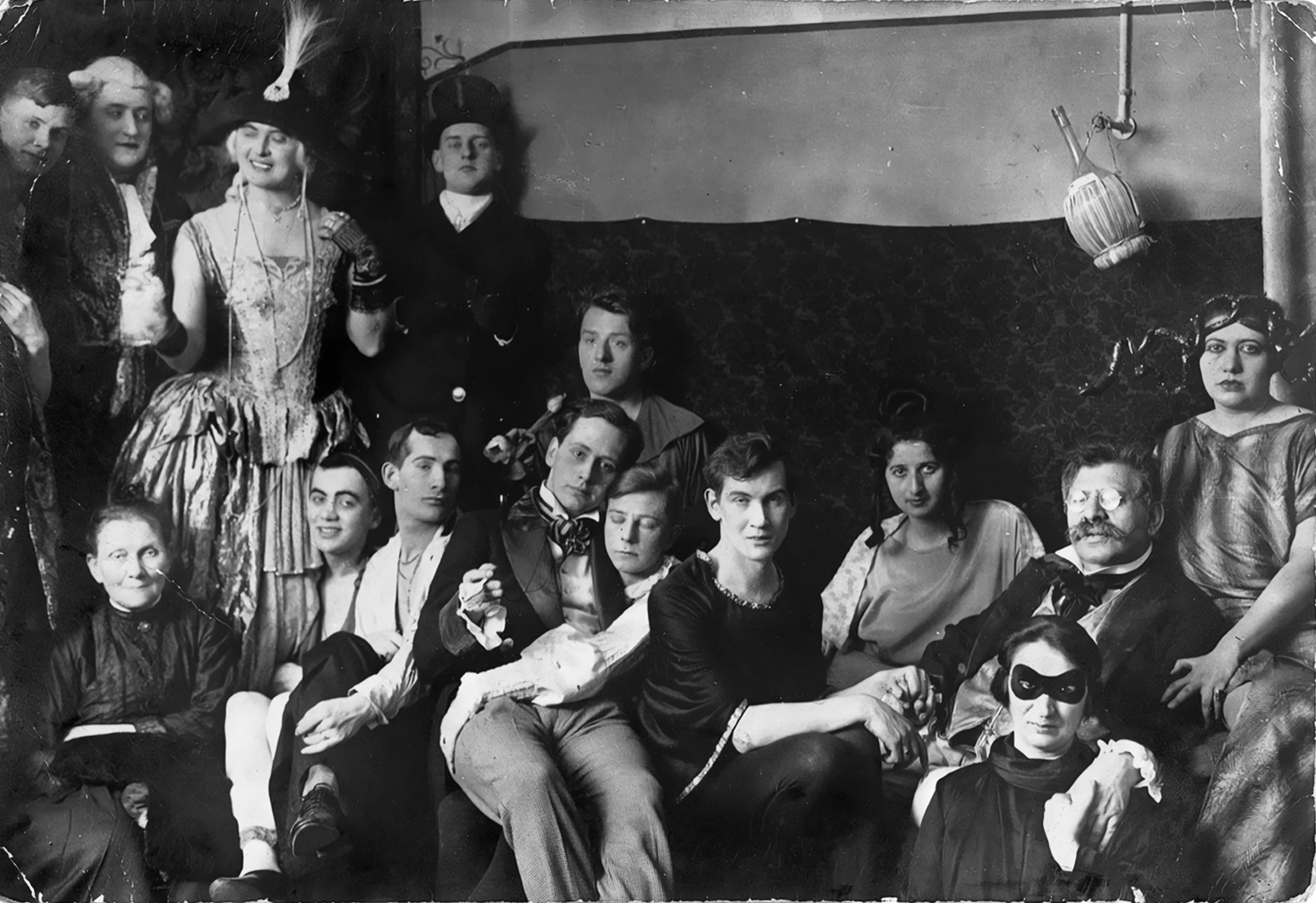

Magnus Hirschfeld (right, wearing glasses) at a costume party at his Institute for Sexual Science.

In 1919, Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin—the world’s first institution entirely dedicated to the study of human sexuality. Psychiatrists, gynecologists, and surgeons worked there, and the institute housed an extensive library of more than 20,000 volumes on sexology. In the early 1930s, in collaboration with surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt, Hirschfeld began performing gender-affirming surgeries—one of the earliest forms of transfeminine transition, from male to female physical characteristics. Patients also received hormone therapy. All procedures were meticulously documented, and the institute’s work drew international interest, making Berlin a global center for sexual science.

The institute’s development was abruptly cut short when the Nazis came to power. On May 6, 1933, members of the German Student Union—a youth organization aligned with the Nazi Party—stormed the building. They seized the entire library to stage a public book burning on May 10 as part of the "Action Against the Un-German Spirit." Speaking at the fire in one of Berlin’s central squares, Joseph Goebbels declared loudly: "The German nation is purifying itself!"

At the time, Hirschfeld was no longer in Germany—he was in France, continuing his academic work in exile. Two years later, he died of a heart attack.

Book burning by German Nazis.

Magnus Hirschfeld’s colleague, surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt—who had played a key role in the early development of gender-affirming surgeries—later aligned himself with the Nazi regime. During World War II, he took part in medical experiments on prisoners at the Dachau concentration camp. This fact has become a striking example of how science can be perverted under an ideology that rejects humanism.

The war and the devastation it brought interrupted the progress of the broader European movement for homosexual and transgender rights for decades. Repression, fear, political instability, and the complete destruction of prewar institutions pushed the struggle for equality to the margins of public attention.

Only in the second half of the 20th century did the United States emerge as a new epicenter of LGBT activism. It was there that mass movements, political campaigns, and advocacy organizations took shape—structures that would go on to influence activists around the world.

Christine Jorgensen and Louise Lawrence Became Pioneers in the Fight for Transgender Recognition in American Society

In the 1950s, the story of Christine Jorgensen gained widespread attention in the United States—she became the first American to openly undergo gender-affirming surgery and a symbol of the early struggle for transgender recognition. At birth, she was named George, but as she later wrote in her autobiography, the sense of inner incongruence had always been present: she saw herself as a woman, despite her male body.

In 1949, at the age of 23, Jorgensen began hormone therapy to ease the symptoms of gender dysphoria. According to her, the treatment relieved her depression and constant internal tension, improved her productivity, and brought clarity to her sense of self. Still, the hormones had only a limited effect on her appearance, and she soon decided to take a further step.

In 1950, Jorgensen traveled to Denmark—one of the few countries at the time where doctors were willing to work with transgender patients. After receiving a medical evaluation, she underwent two surgeries in 1951 and 1952: the removal of her testicles and penis. In her memoirs, she recalled feeling truly alive and confident in herself for the first time after the transition.

On December 1, 1952, the New York Daily News ran her story on its front page, instantly turning Jorgensen into a national sensation. The public reaction was mixed—ranging from sympathy and admiration to ridicule and condemnation. Nevertheless, attention to her story did not fade, and Christine used her visibility to launch a campaign for transgender rights. She appeared regularly on television, at universities, and on public forums, speaking about her life and the possibilities of medical transition—laying the groundwork for a future movement toward gender recognition.

New York Daily News issue featuring Christine Jorgensen.

During the same period, Louise Lawrence played a significant role in shaping the early American transgender movement. Assigned male at birth, Lawrence chose not to undergo surgery—despite knowing it was possible—and instead focused on hormone therapy, devoting herself to public advocacy and education rather than medical transition.

She built informal networks within what was then a highly fragmented trans community: maintaining correspondence, sharing contacts of doctors willing to provide hormone treatment or perform surgery, and helping to distribute information that was extremely difficult to access at the time. Alongside this, Lawrence gave public lectures explaining the nature of transgender identity and challenging the myths that surrounded the subject.

It was at one of these lectures that Louise Lawrence met Virginia Prince—another pioneer of trans activism in the U.S. In 1952, they co-founded Transvestia: The Journal of the American Society for Equality in Dress. Though only two issues were published, the magazine’s appearance marked a turning point. Transvestia became the country’s first publication dedicated to the experiences of transgender and gender-nonconforming people and signaled the emergence of an independent movement, distinct from the era’s mainstream gay and feminist activism.

Rights That Still Need Defending

During #MeToo, Tina Johnson Spoke Out About Harassment

Eight Years Later, She Regrets It—Support Has Vanished, and What Remains Are Lawsuits, Debt, and Silence

Violence Is Widespread, Trust Is Not

Most Surveyed Women in England and Wales Have Faced Harassment, but Only a Third Trust the Police

Support for Abortion Rights Is Declining Among Men

Women Have Become More Vocal Since the Repeal of Roe v. Wade

The Retreat From Equality Begins With Women

Corporations Are Dismantling DEI Programs, Narrowing Access to Power for Those Who Don’t Fit the ‘Traditional’ Leader Mold

In 1966, Transgender People Stage the First Mass Protest Against Police Violence—Laying the Groundwork for a Political Movement

While the 1969 Stonewall riots are widely regarded as the beginning of the mass LGBT rights movement in the U.S., an equally pivotal moment for the transgender community occurred three years earlier—in 1966, in San Francisco. In the Tenderloin district, at Compton’s Cafeteria, transgender people and cross-dressers organized what became the first documented act of resistance to police violence in U.S. history. This event marked the start of a trans political movement: in the aftermath, support and advocacy initiatives began to emerge across the country.

In the 1960s, Compton’s Cafeteria was one of the few public places in San Francisco where transgender people could gather without the immediate threat of arrest. Even so, the environment remained hostile. The management routinely called the police to remove "undesirable" patrons—under laws that criminalized "cross-dressing" in public, this was standard practice. Gay men and trans women were regularly subjected to humiliating checks and harassment. Trans women, in particular, often lacked support even within the gay community and were forced to seek alternative spaces for connection and solidarity.

Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco. 1970.

According to eyewitnesses, the riot erupted after a police officer, summoned by the café manager, struck one of the patrons. In response, the room erupted in shouting, tables were overturned, and dishes, utensils, and eventually heavy handbags—one of the few available forms of self-defense—were hurled at the officers. The rioters damaged a police car and set fire to a newspaper stand outside the café. One participant later recalled: "We were tired of being harassed. Tired of being forced to use the men’s restroom even though we were dressed as women. We wanted our rights to be respected."

Drag queen Colette LeGrande, a regular at Compton’s Cafeteria, later said: "If Stonewall was the beginning of the gay rights movement, then the Tenderloin riot was the same for trans girls."

Despite Gains, Trans People Face Rejection Within the LGBT Community and Ongoing Stigmatization in Society

By the late 1960s, transgender activists were closely connected to the broader queer movement and played a prominent role in the Stonewall riots, which became a symbol of the LGBT struggle for equal rights in the United States. But by the 1970s, the trans community faced a new form of isolation—this time not primarily from the state, but from within the movement itself. Despite some achievements—such as easier procedures for legal gender change and expanded access to medical care—trans people encountered growing estrangement within the LGBT movement.

Among segments of gay and feminist activists, a belief took root that transgender individuals were not dismantling but rather "reproducing" gender stereotypes, seeking to conform to them through hormone therapy and surgical intervention. Trans women in particular were frequently accused of "betraying" the feminist cause—of substituting the fight to broaden definitions of womanhood with efforts to "fit into" patriarchal expectations.

The most influential articulation of this rhetoric came from radical feminist Janice Raymond’s book The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, published in 1979. In it, she argued that transgender identity was a product of patriarchal culture designed to "colonize" female bodies, and that trans women posed a threat to women’s spaces. This perspective gained traction in several organizations and laid the groundwork for years of marginalization of trans activists within the queer community.

Still, the movement did not stop. In 1975, the city of Minneapolis passed the first U.S. law prohibiting discrimination against transgender people. In 1977, the New York State Supreme Court ruled in favor of transgender tennis player Renée Richards, affirming her right to compete in the women’s division of the U.S. Open.

Renée Richards—the first transgender tennis player permitted to compete in the women’s division of the U.S. Open.

In 1987, the American Psychiatric Association included the term "gender identity disorder" in its diagnostic manual, the DSM—a move that gave transgender people access to medical care but also reinforced their classification as patients with a "disorder." Despite the ambiguity of such a label, it became an important legal and medical precedent.

In 1993, Minnesota became the first U.S. state to extend anti-discrimination protections to transgender people, followed by Rhode Island in 2001. In 2003, George W. Bush became the first American president to host a transgender person at an official White House event.

In 2008, trans woman Stu Rasmussen was elected mayor of Silverton, Oregon—marking the first time in U.S. history that an openly transgender person held an elected office at that level. And in 2009, Chastity Bono, daughter of singer Cher, announced the beginning of her gender transition—her coming out became one of the most visible moments in American pop culture at the time.

Singer Cher and her transgender son Chaz (born Chastity).

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association took a significant step toward destigmatizing transgender identity: in the new edition of its diagnostic manual, the DSM, the term "gender identity disorder" was replaced with "gender dysphoria." The change emphasized that the condition was not pathological, but rather a state in which an individual experiences distress due to a mismatch between their gender identity and the sex assigned at birth. This allowed continued access to medical care while reducing the stigma associated with mental illness.

Two years later, in 2015, President Barack Obama became the first head of state in U.S. history to publicly mention transgender people in a State of the Union address. The symbolic gesture was widely seen as a mark of official recognition and a milestone in legitimizing transgender visibility in American politics and society.

Efforts to Simplify Legal Gender Recognition Spark Fierce Debate—Deepening Divides Within the LGBT Community and Broader Society

As transgender visibility increased in the West, so too did public debate over the legal and social status of trans people. The controversy was especially intense in the United Kingdom, where in 2017 the government proposed a reform aimed at simplifying the process of changing one’s gender marker on official documents. A key element of the initiative was so-called demedicalization—removing the requirement to present medical evidence in order to legally affirm one’s gender identity.

By 2018, the discussion had escalated into a full-scale political and cultural conflict. Opponents of the reform expressed concern that allowing gender changes on legal documents without medical oversight would lead to abuses—particularly regarding access to "women-only spaces" such as restrooms, changing rooms, crisis centers, or prisons. One high-profile case involved Karen White, a transgender woman convicted of sexually assaulting fellow inmates in a women’s prison. At the time, Britain’s The Times warned that the proposed reform would "destroy women’s sports" and allow "former men" to dominate competitions.

Controversial banner reading "Trans Activism Erases Lesbians" at London Pride. 2018.

Divisions also emerged within the LGBT community. At London Pride in 2018, a group of activists from the organization Get the L Out took to the streets with a banner reading "Trans Activism Erases Lesbians," calling for the recognition of lesbians as an autonomous group, separate from the trans rights agenda. Pride organizers later issued an apology, calling the protest "shocking and unacceptable."

According to British trans activist Christine Burns, before these debates began in 2017, major UK outlets such as The Times and The Sunday Times published no more than six articles per year on transgender issues. After the reform was introduced, that number rose to 150 annually—and the tone became markedly more hostile.

To this day, debates over transgender rights remain unresolved in British society. Since 2022, according to reports from the advocacy network Transgender Europe, there has been a rise in conservative sentiment in the country. On matters of trans rights, the UK now lags behind most of Western Europe, though it still ranks ahead of Eastern Europe. The most progressive countries in this area remain Iceland, Spain, Belgium, and Finland.

Executive Orders Issued in 2024 Threaten Trans Rights and Raise Fears of Renewed Institutionalized Discrimination

Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 U.S. presidential election reignited a fierce national debate over transgender rights. During the campaign, Trump leaned heavily on transphobic rhetoric to mobilize conservative voters. Upon returning to the White House, he launched an aggressive agenda aimed at systematically stripping transgender people of their civil rights.

On Inauguration Day—January 20—he signed an executive order titled "On Protecting Women From Extremist Gender Ideology and Restoring Biological Truth," which legally reimposed a binary definition of sex in the United States: exclusively male or female. Another order reinstated the ban on transgender people serving in the military. A third—"On Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports"—barred transgender women from competing in women’s athletic events. Simultaneously, all federal programs promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) were dismantled across government institutions.

Trump signs executive order banning transgender women from participating in women’s sports.

Trump had made a similar attempt to ban transgender people from military service during his first term. That order was later overturned by the Biden administration—an example of how executive actions in the American political system remain in force only until the next president chooses to reverse them. In theory, Trump’s transphobic directives could be rescinded again by his successor. But in practice, this means that the transgender community in the U.S. is granted or denied recognition on a rolling, inconsistent basis—living in a state of legal uncertainty every four years.

Prior to this political shift in the U.S., public support for transgender people had been steadily rising. According to a survey conducted by the University of Minnesota in August 2022, 83% of respondents believed that trans individuals should have the same rights as the cisgender majority. But the measures introduced by the Trump administration pose a threat not only to this American minority. For years, the United States had served as a global reference point for LGBT rights—especially during the Obama and Biden presidencies. Now, Washington’s transphobic and homophobic agenda risks becoming a model for authoritarian governments and right-wing populist movements in Western democracies.

Rights That Still Need Defending

Trump Revokes Emergency Abortion Protections in Hospitals. The Rule Had Required Doctors to Save Women With Life-Threatening Complications