The story of Shahrokh Heidari offers an insider’s perspective on a country where freedom of speech comes at the cost of life. His works expose the regime and bring the world’s attention to the repression in Iran.

In the interview, the artist shared memories of his childhood, shaped by revolution and war, explained why he was forced to leave his hometown, and revealed how art became his means of resistance.

Shahrokh, when looking at your illustrations, one strong impression emerges, which can only be verbally expressed as, "Iran brings death to anyone who does not comply with the authorities of this country". Is that accurate?

Answering this question, I’ll share a personal story from my life. When I was young and living in Ahvaz, a city in southern Iran, I would often pass by several prisons on my way to school. One of them was the infamous Karun Prison, where public executions were carried out almost weekly. Driving past it, I would see a gallows set up, and sometimes, someone hanging from it. On rare occasions, someone would be pardoned, and people would celebrate it.

In Ahvaz, located near the frontlines of the Iran-Iraq War, I was constantly confronted with death. My childhood coincided with the 1979 revolution and, two years later, the outbreak of the war. These events profoundly shaped my worldview.

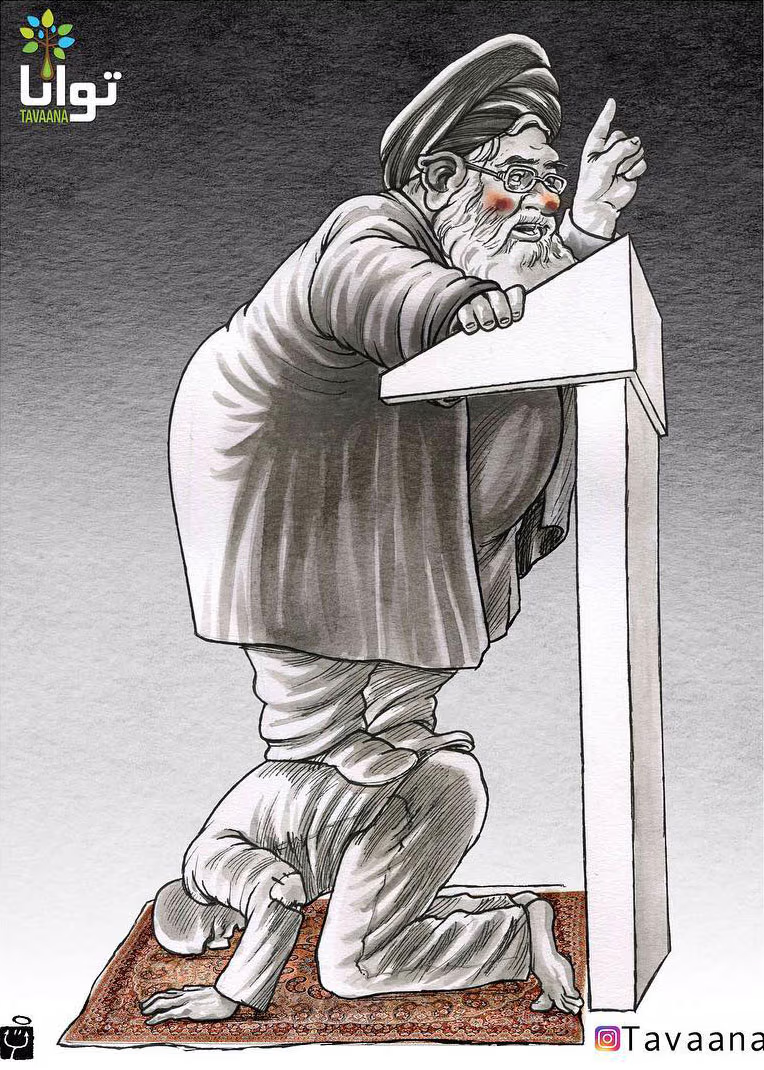

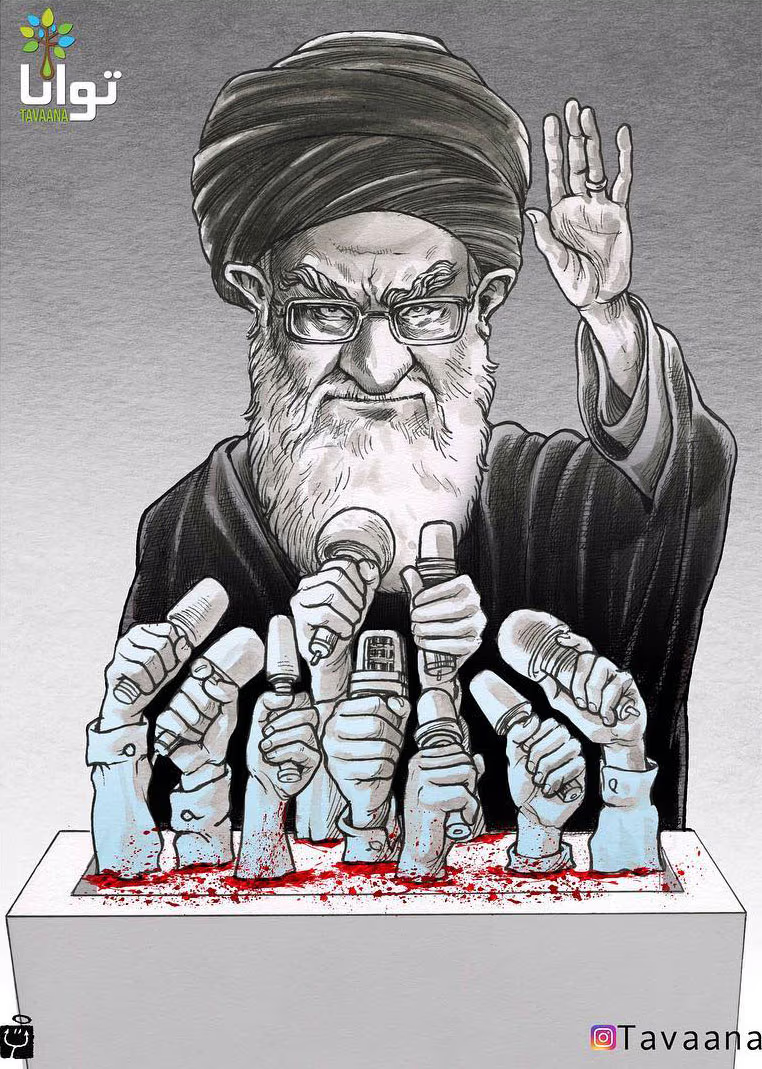

The repeated loss of friends and acquaintances deeply affected me and my work. It’s hard to depict optimistic scenes when your past is filled with darkness. The last 150 years of Iran’s history are marked by fear, deprivation, and death for the people living in this country. You never know which rights will be restricted next. In Iran, there is no room for open criticism, especially toward figures like the Supreme Leader. You won’t find a single interview or public conversation involving Khomeini or Khamenei over the past 40 years.

The lives of writers and artists in Iran can be compared to a constant feeling of suffocation. That’s why my works are a way to depict the realities.

According to international human rights organizations and Together Against the Death Penalty, 432 people were executed in the Islamic Republic in 2022. The number of executions increased by 13% compared to the previous year.

Those who sow death reap anger. According to Amnesty International, the number of executions in the Islamic Republic reached its highest level in eight years in 2023, with the government executing 853 people in just one year.

The Language of Execution. In August and September 2024, the number of executions in Iran sharply increased: around 90 executions were carried out in August alone, many without fair trials and based on confessions obtained under torture. Among them was the execution of Reza Rasai, one of the detained participants in the 2022 uprising.

How are the relations between the authorities and society structured in Iran?

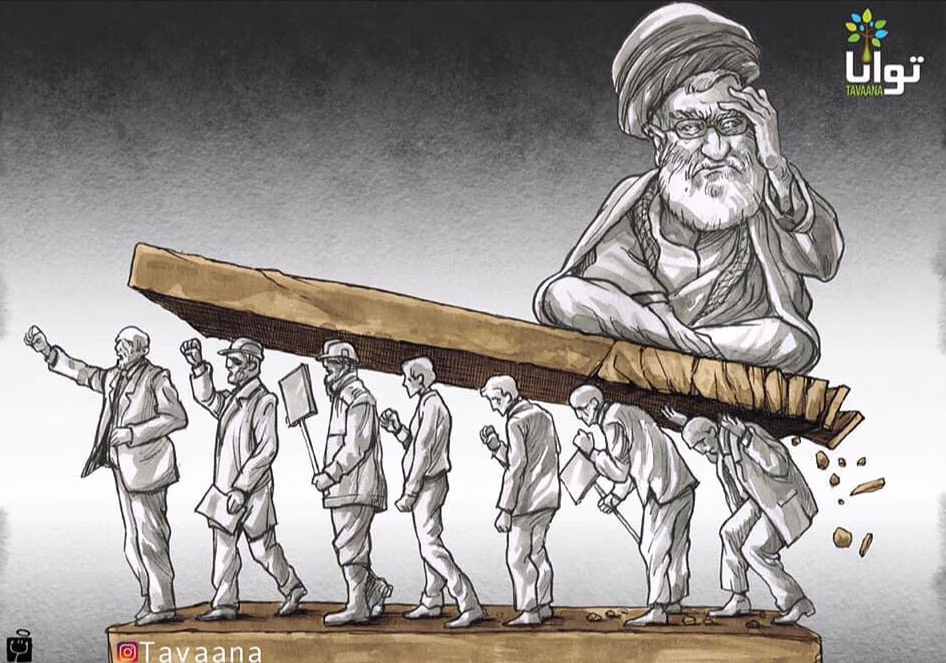

The relationship between the Iranian government and its people is built on a foundation of repression and control. Recent events and the harsh response to protests highlight both the potential for change and the government’s fear of the people’s voice. For a long time, the authorities have tried to maintain control over society through enforced silence.

This growing divide between the people and the government has eroded trust. Instead of addressing the needs of society, the government suppresses any form of dissent, going so far as to shut down the internet and impose complete censorship on the media. As someone who sought to directly expose inconvenient truths to the government, I have faced these restrictions and repressions firsthand.

You take a risk even when expressing your views through veiled symbols. At the same time, the Iranian authorities organize and hold art festivals, often on anti-Israeli themes, promoting Holocaust denial. It’s worth noting that prizes at these festivals amount to several thousand dollars.

Since 2012, you’ve been living in Paris. What exactly compelled you to leave Iran? When and why did you realize that you needed to leave?

In 2012, I arrived in Paris on an academic scholarship without any intention of staying long-term or seeking asylum. My plan was to study, deepen my expertise, and perhaps return to Iran later. At the time, I managed to continue working despite the pressure and threats. My decision to ultimately stay in France was driven by a specific event.

My friend Mana Neyestani asked me to support a campaign for a cartoonist in Iran who had been sentenced to flogging for depicting a government official in a caricature. In solidarity, I created a cartoon that went viral, which made me an enemy of Islam. After that, any possibility of returning to Iran disappeared.

Since then, I have been actively collaborating with publications and media outlets that cover life in Iran. I decided to stay and continue my work here.

Shahrokh Heidari.

Where did you learn to draw, and who was your teacher?

My journey as a cartoonist began unintentionally. As a child, I could easily recreate any image I saw, such as characters from cartoons, on paper. I also loved watching football and would draw portraits of players. I was self-taught in art, never attending formal drawing lessons, but I passionately followed my interests and gravitated toward more complex subjects.

My family hoped I would pursue metallurgy or another practical profession, like my father, who worked at a steel mill. However, I chose to enroll in an art school. My family did not approve of this decision.

In my first year of art school, I participated in a cartoon exhibition dedicated to social issues in Iran, which became a turning point for me. I realized that caricature is a universal language through which I could express my worldview.

After graduating from school and during my university studies, I actively collaborated with student publications, earning several awards for my work. Overall, my education allowed me to shape my approach, refine my skills, and develop my unique style.

How do you come up with the imagery for your works?

My process of creating a caricature often begins with my personal experiences, thoughts, or feelings about topics like war, poverty, love… I divide my works into two categories: those I create for media outlets and those I create for festivals or competitions. The second category tends to be more candid, as it allows me greater freedom of self-expression.

I sketch ideas, observe people, and engage with the real life around me… All of this inspires me and helps me find the right form, metaphor, or symbol to subtly and creatively reveal the topic.

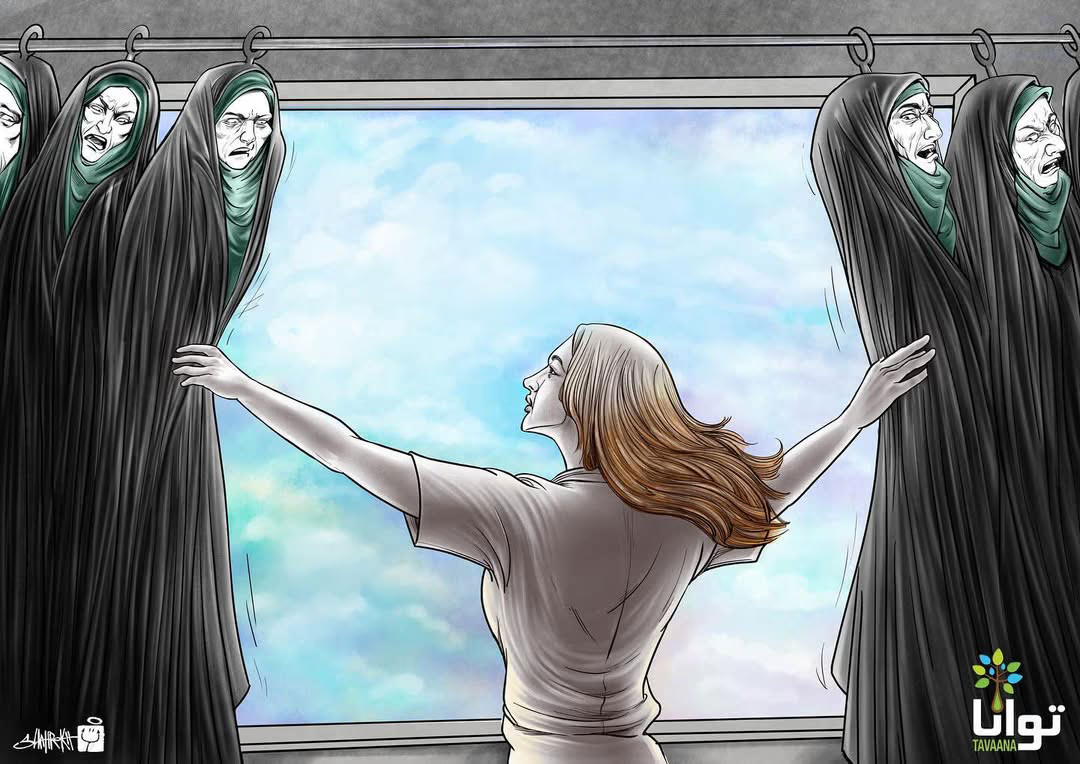

One of the fundamental rights of women violated in Iran is the right to choose their clothing. The mandatory dress code symbolizes the ideology of the ruling clerics.

The Sky of Freedom. Freedom of choice represents the liberty of citizens to make diverse decisions under the auspices of a democratic government that safeguards civil rights.

Are there any opportunities for self-expression in Iran?

It depends on the subject matter of the work. In Iran, there are good galleries and talented artists, some of whom manage to express dissent through abstract works. However, for a cartoonist who wants to directly illustrate political or religious issues, it is impossible to do so.

For example, if a cleric bans a concert in Khorasan, a cartoonist would never be allowed to depict this critically. Direct criticism is entirely forbidden, and artists must find subtle ways to express their opinions to avoid facing severe consequences.

There are artists who support the regime. They can freely work in Iranian media, receive rewards, and enjoy a stable livelihood. However, anyone who challenges the regime will inevitably be suppressed.

What are the goals and priorities of the Iranian authorities today? Have they changed in recent years? To what extent do these goals align with the expectations of society?

The goals of Iranian leaders have remained largely unchanged in recent years. They prioritize maintaining and expanding their power, employing tools ranging from suppressing dissent to imposing strict restrictions on social and cultural spheres. The government’s approach reflects its relentless pursuit of control and silencing any opposing voices.

The Iranian regime organizes cartoon festivals promoting Holocaust denial or anti-Israeli themes, offering generous cash prizes. However, most professional cartoonists avoid participating in them. To maintain their independence, free artists have turned to fields such as illustration and animation.

Recently, we learned from the media that Iran has unblocked WhatsApp and Google Play and suspended the law tightening hijab-wearing rules. Does this indicate that the Iranian authorities are striving for democracy?

In my view, this seems more like a temporary painkiller than real steps toward democracy. When the Iranian government faces internal or international pressure, it makes minor concessions. This has happened repeatedly, but these changes have never been long-term.

The problem goes beyond the hijab law or internet access—these are merely symptoms of a larger systemic issue rooted in the country’s political and legal structure. A democracy is a place where people can freely choose, speak, and shape their own destiny. In Iran, these rights are severely restricted, and the recent measures are more likely aimed at suppressing protests than genuinely striving for democratic progress.

Of course, there is an opinion that even small shifts like these could be the first steps toward broader reforms. As people become accustomed to these relative freedoms, they may demand more, eventually leading to fundamental change. However, experience shows that such optimism rarely translates into tangible results, as the Iranian government has consistently “taken back” these concessions whenever it suited their interests.

Have you received any reactions to your works from Iranians inside the country or abroad? What were they?

As an artist striving to voice the perspective of those who are denied the opportunity, I have received significant feedback. I collaborated with several opposition media outlets outside of Iran, including Radio Farda, BBC Persian, Tabnak, and Asou. My works have also been published in French media, such as Courrier International, Le Monde, and Le Canard Enchaîné.

I also see my works being printed on posters by protesters outside of Iran. Comments and reposts on social media allow me to indirectly reach different people and feel the significance of my work.

Sometimes I’ve seen some of my cartoons on the front pages of Iranian publications, placed there without my permission. They are often altered or censored, but the experience is still fascinating.

All these years, Iran has supported Russia in its war against Ukraine. What, in your opinion, is the reason for such an alliance?

The alliance between Iran and Russia is based on shared interests rather than ideological or strong historical ties. Both countries have a common adversary in the West—the United States—which has brought them closer together. Iran’s support for Russia in the war against Ukraine, from supplying drones to intelligence cooperation, is part of this shared strategy. Firstly, the Iranian government seeks to profit from arms sales, and secondly, it aims to assert its significance in global politics while opposing Western influence.

However, in my opinion, this relationship resembles a one-sided deal. Russia benefits significantly from Iran’s support, but if a critical situation arises within Iran itself, Russia will prioritize its own interests.

At the same time, some believe this alliance is beneficial for Iran as well. Having an ally like Russia could strengthen its position on the international stage. However, in reality, Russia has often proven to be an unreliable partner, and the burden of this alliance will ultimately fall on the shoulders of the Iranian people.

From my perspective, these events resemble a political spectacle. In my work, I always strive to depict how every political decision places a burden on the people, while the only beneficiaries are the politicians comfortably settled in their positions.

Will you ever return to Iran? Do you see any prospects for change in the country?

Even artists outside Iran fear depicting the country’s clerics, worried about potential consequences. A single caricature could lead to a lengthy prison sentence—15 years or more—or even the death penalty if the artist were ever to set foot in Iran. I was one of the first to openly, without subtle forms, depict Khamenei himself and directly criticize him (Ali Khamenei is an Iranian political figure, designated as the Supreme Leader of the country — editor’s note). I have created over 200 caricatures of him and his ideology. There is no place for me in Iran! I don’t even consider such a possibility.

As for whether I see any prospects for change, I believe it will take several generations. It’s a gradual evolution in which people must learn to assert their rights and hold those in power accountable. Today, we see women protesting and voicing their opinions—something unimaginable just a few years ago. This is the result of progressive steps toward democracy, and I believe that young Iranians, more than anyone else, have the ability to shape their own future.

This progress will be slow and limited; real change will come when the dictatorship weakens from within or is challenged by the people. I remain optimistic about Iran’s future, but I understand that it is a long-term process.