At the 100-day mark as chancellor, Friedrich Merz finds himself in visibly weakened political shape. Some 67% of respondents say they are dissatisfied with the CDU leader’s performance, while the ruling party has lost its lead in the polls to the far-right AfD. The figures are substantially worse than those recorded in the first hundred days of Olaf Scholz or Angela Merkel. Analysts stress that the problem goes beyond Merz himself: Germany is facing a deep political, economic, institutional, and values crisis. The social fracture may prove more dangerous than economic hardship, with consequences likely to become visible in the 2026 elections at every level.

AfD’s Rise and the Crisis of Party Identity: How Germany’s Electoral Landscape Has Shifted

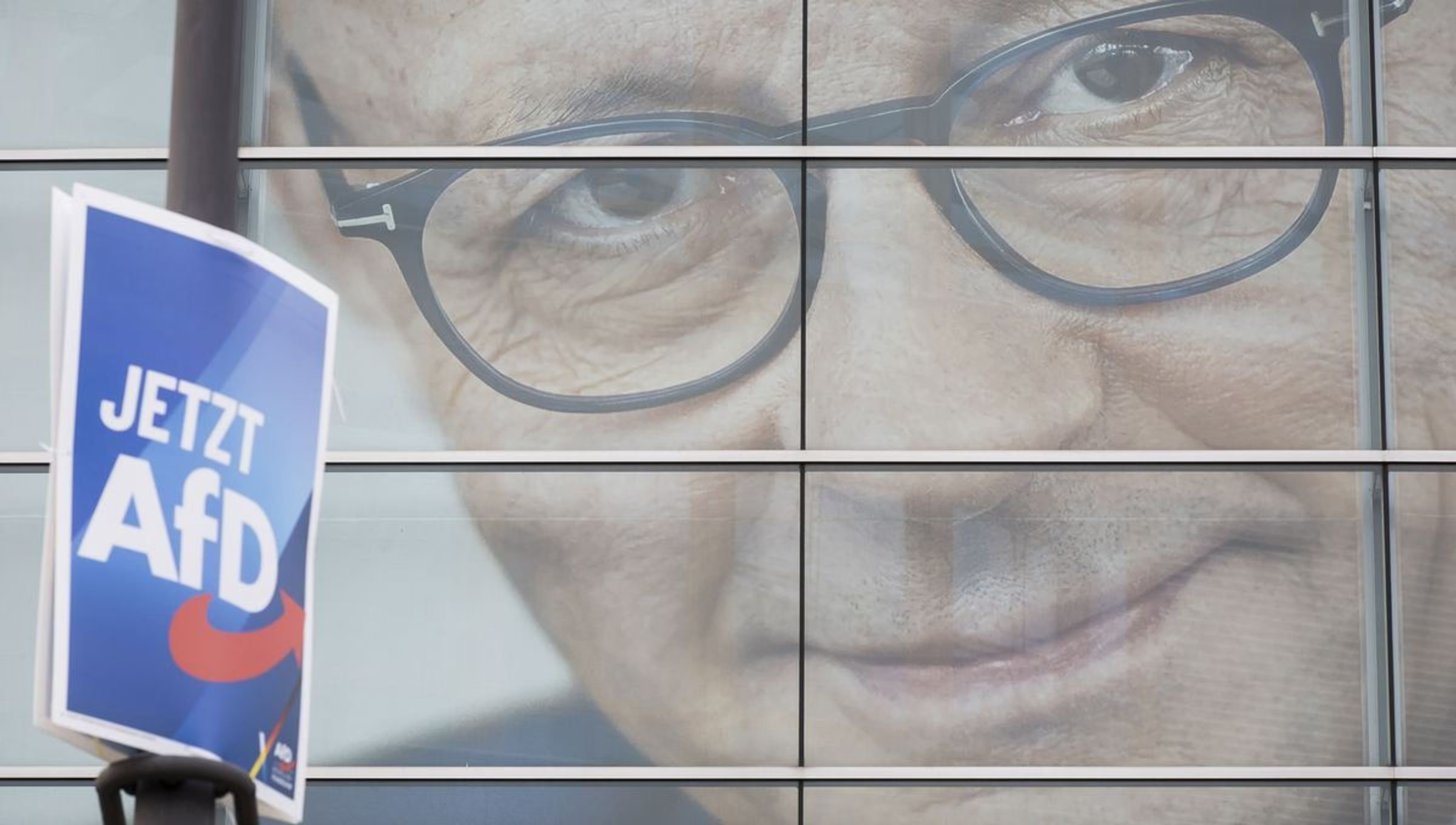

One of the key barometers of Germany’s domestic politics in recent years has been attitudes toward Alternative for Germany (AfD) and its electorate. Despite harsh criticism from civil society, increasingly radical rhetoric skirting the limits of legality, and its designation as a right-wing extremist force—first in some federal states and later nationwide—the party has grown from 11% support in August 2020 to 26% in August 2025.

The AfD has secured a firm foothold in both the Bundestag and regional parliaments, won control of one federal state, placed second in a series of contests—from European to state and federal elections—and in some districts captured an outright majority. It has become a permanent fixture in German politics, and its opponents have yet to formulate a convincing response to this challenge.

Surveys suggest that between a quarter and a third of German voters have lost stable party identification and are prone to shifting their preferences situationally, with some deciding only once they are at the polling station.

The era when generations voted for the same party is rapidly fading. On the right, a bloc of voters has emerged who are prepared, depending on circumstances, to back either the CDU (or the CSU in Bavaria) or the AfD. Whereas casting a ballot for the far right was once seen as disreputable, moral barriers have visibly weakened.

It was precisely this constituency that proved decisive for Friedrich Merz. A staunch conservative and critic of Angela Merkel’s centrist-liberal course, he campaigned in the snap February 2025 election on offering a “democratic alternative” to voting for the AfD: tighter control of migration, a stronger international role for Germany, and faster economic growth.

The initial effect was positive. Right-leaning conservatives significantly boosted CDU’s tally, enabling Merz to form a government. His “law and order” rhetoric appealed to anti-immigrant voters: stricter border controls, tougher asylum procedures, and the deportation of “undesirable foreigners” aligned with their expectations. But those expectations were only partly fulfilled.

Right-wing circles demanded far harsher measures—steps unlikely to win the support of the Social Democrats (SPD), CDU’s coalition partners, and perhaps in conflict with Germany’s international obligations or open to legal challenge. Merz is a conservative, but he is also a democrat, and he could not step beyond those boundaries.

By the May vote on Merz’s chancellorship in the Bundestag, it had already become clear that the new chancellor did not fully control his own party and parliamentary group. In some sense, he became a hostage of his own moves: having prevailed in the intraparty struggle and, on his third attempt, secured leadership of the CDU, Merz focused on sidelining centrists loyal to Angela Merkel and her unsuccessful successor Armin Laschet. That task was accomplished, but with the right-wing conservatives came an agenda further to the right than Merz himself, forcing him into concessions—such as withholding support for an SPD nominee to the Constitutional Court deemed “too leftist” by ultra-conservatives, and pushing to the margins centrists popular within the party, such as Norbert Röttgen and Dennis Radtke.

Calls to tear down the “firewall”—the voluntary commitment by democratic parties not to form coalitions or cooperate with the AfD—remain muted at the federal level and largely confined to procedural issues. Jens Spahn, head of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group, for instance, suggested that AfD should be treated like a “normal opposition party” in the allocation of committees and commissions.

Until now, democratic parliamentary parties have consistently refused to vote for AfD candidates. But at the state and municipal levels, Merz’s fellow party members are far more outspoken. Saskia Ludwig, a CDU member of the Brandenburg state parliament, openly proposed forming a coalition with the AfD, calling it “center-right,” and urged colleagues to “be more relaxed about our democracy and respect the will of the voters.”

Those pushing to steer the CDU toward cooperation with the AfD find allies even on the far-left flank. Sahra Wagenknecht, leader of the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance, has argued for such a coalition, criticizing the “old parties without a clear profile” and stressing that “you cannot simply ignore a party supported by one in five voters, and by one in three in the east.” Similar assessments are not limited to radicals: today, 40% of Germans oppose the “firewall,” and 68% expect the AfD to secure its first state premier as early as next year.

Thus Merz finds himself caught between two fires. On one side, millions of citizens not only regularly vote for the AfD but also hold views at times further to the right than the rhetoric articulated by Alternative for Germany itself. Advocates of “accepting the inevitable and seeking cooperation” are growing louder inside the chancellor’s own party; extremist rhetoric and proposals at or beyond the edge of legality no longer deter them. A “lite AfD” on democratic terms has failed, and democracy itself is no longer treated as sacred or unquestionable.

On the other side, a significant share of society sees the AfD as an existential threat to the postwar constitutional order of the Federal Republic. The millions who marched in 2024 against the far right have not disappeared. Their hostility toward Merz—whom they regard as failing to counter the danger and, in effect, enabling the radicals—is intensifying. Merz has yet to find a convincing strategy to engage with these groups; it may be that none exists.

Merz’s Economic Agenda: The “Debt Brake,” Recession, and the Limits of Coalition Politics

A central element of Merz’s political identity has been, and remains, his demonstrative competence in economics. The current chancellor has repeatedly stressed that his predecessors viewed the economy through the lens of bureaucrats, whereas he—having worked as a business lobbyist and adviser to leading global companies—understands the logic of markets from the inside. He opposed expanding public debt and rejected “left-leaning, politicized projects” he argued were too costly for the budget.

One of the most contentious issues has been the debate over the so-called “debt brake”—a constitutional provision that caps the annual increase in debt at no more than 0.35% of GDP. Conservatives argued that the “debt brake” must be preserved, while centrists and the left insisted that, given the domestic and international crises, it could be relaxed—especially since the law explicitly allows exceptions in extraordinary circumstances.

Already in March, after winning the election but before formally becoming chancellor, Merz was forced to compromise on his principles. Rushing a vote through the outgoing Bundestag, his future coalition partners from the CDU/CSU and SPD, with Green support, effectively lifted restrictions on defense and security investment. Merz found himself in a trap. On the one hand, he knew he was breaking a key campaign promise and that conservative voters would remember it. On the other, without softening the “debt brake,” there was simply no way to fund ambitious plans for strengthening defense and rearming the Bundeswehr. By siding with the much-disliked “red-greens” in his camp, he set himself up for criticism within conservative ranks.

Even the CDU’s official 100-day publication describes his economic record only in outline, focusing less on concrete achievements than on intentions—Germany’s exit from recession and vague “growth impulses.” Tangible breakthroughs are indeed absent. The Federal Republic, the world’s third-largest economy by GDP, remains in recession. The German Economic Institute projects a 0.2% contraction in GDP in 2025—a grim figure compared with forecasts for the EU overall (+0.8%), the United States (+1.3%), and China (+4%).

The negative trend is hitting Germany’s automotive industry and construction sector—pillars of the economy—as well as the labor market. Even the government’s more optimistic projections anticipate stagnation. Manufacturing output has fallen by 1.9%, the steepest drop since 2020.

Two structural factors, beyond the reach of any chancellor’s decree, weigh on growth. First, the external environment is unfavorable for Germany, especially in traditional industries such as automotive and machinery: German products are costly due to high wages and energy prices, and less competitive than those from countries benefiting from direct or indirect state support. Second, Germany struggles with poor digitalization, aging infrastructure, and a heavy tax and social insurance burden. Analog bureaucracy—with its sluggishness and maze of permits, from business registration to building codes—remains, in the eyes of experts and expatriates, a major obstacle to development.

It would be wrong to say the current cabinet is inactive. Since the coalition was formed, a dedicated ministry for digital technology and state modernization has been created, and steps have been taken to streamline paperwork. Yet here, as on the ideological front, Merz finds himself in an electoral trap. Much of the public wants tangible results “here and now”: falling inflation and cheaper energy in July are not seen as his achievements and bring no boost in approval. Likewise, the initiative by 61 companies, which united under the banner Made for Germany and pledged €631 billion in investment through 2028, went largely unnoticed. Government praise from bankers sounds to ordinary voters like a “club of the wealthy” with no clear benefits for the poor or the middle class.

At the same time, experts demand action today rather than just plans for tomorrow. A different, conservative part of society—those who prefer cash and paper forms over online services—view digital transformation as a threat and a tool of expanded state control. For these circles, the “old Federal Republic” before 1990 has become a symbol of a “lost paradise”—not unlike the USSR for nostalgics in the post-Soviet space.

The New Chancellor’s Foreign Policy: Ukraine, NATO, and the Attempt to Build Ties with Trump

During the campaign, Friedrich Merz presented himself as a politician deeply engaged in global affairs, positioning himself as the “anti-Scholz.” While his predecessor—first as finance minister and earlier as mayor of Hamburg—showed little interest in foreign policy, Merz pledged to raise Germany’s international standing, establish working relations with Donald Trump and other “difficult” leaders, and expand both the scale and effectiveness of support for Ukraine.

Those promises have largely been kept. His June visit to Washington was a success for Germany. In Poland, the new chancellor was received as a partner—no small achievement for a German leader given the long list of fraught issues, from historical grievances and EU agricultural quotas to disputes over border controls.

Berlin has also become more assertive on Ukraine—not only in terms of material support (already substantial under Scholz) but also in diplomacy and European coordination. A telling example was the emergency online meeting Merz convened at record speed ahead of the Trump-Putin talks in Alaska: participants included European leaders, the European Commission president, the NATO secretary-general, the U.S. president and vice president, as well as Volodymyr Zelensky. Even outlets critical of the chancellor acknowledged that at the recent Washington summit he succeeded in conveying a united European stance to Trump, establishing rapport, “squeezing out almost the maximum,” and making a tangible contribution to shaping the EU’s common line.

The chancellor has also been active within NATO: the June summit highlighted how vigorously Merz worked to persuade allies of Germany’s reliability and strength. In his first months in office, support for Ukraine expanded; Berlin, the first to agree to purchase U.S. weaponry for Kyiv, became deeply involved in securing Patriot systems and other critical components of Ukraine’s defense.

Yet even on the foreign policy front, Merz is constrained by expectations and limits. Germans have a sober view of Berlin’s real influence: only 13% believe Merz can meaningfully sway Trump, while 84% think otherwise; even among CDU voters, 73% are skeptical. This aligns with the country’s internal value divide. On support for Ukraine, society is almost evenly split: some favor maintaining or even expanding aid, others see little point. As a result, the chancellor faces criticism from both sides: supporters of Kyiv fault him for hesitation (like his predecessor, he refuses to send Taurus missiles to Ukraine), while isolationists denounce the “squandering of taxpayers’ money” and see Merz as merely continuing Scholz’s line.

A similar divide has surfaced in views on the Middle East conflict. Demonstrations are held both by supporters of Israel and by its critics. For some, Merz “enables the genocide of Palestinians,” while for others—by reducing arms deliveries to Israel—he “forgets Germany’s historic responsibility to the Jewish people.”

Social Division and Crisis of Trust: Why Germany Cannot Find a Unified Course

Supporters of a Make Germany Great Again approach (with the caveat that, for obvious historical and political reasons, the German equivalent of “great” is never applied to Germany) expected from Merz, if not miracles, then at least a kind of “great leap”—rapid transformations aligned with their vision. These expectations were impossible to meet, even if in his first hundred days he had not made a single mistake.

Subjective factors also play a role. Merz inherited the federal government’s chronic problem with communication. His July remark praising the European Commission for securing an EU-U.S. tariff deal at “only” 15% instead of 27.5% was a case in point: to the broader public, it sounded unconvincing. Yet the main reason for his sliding approval lies deeper than isolated missteps.

The country is undergoing an institutional and identity crisis—less visible from the outside than the economic downturn, but no less dangerous. Yes, the economy is faltering, and on the global stage Germany struggles to compete with China and the United States. But the growing social divide matters more and, in the long run, could prove more consequential than today’s growth problems.

A significant share of citizens no longer feel bound by the written and unwritten rules rooted in what was once considered “the most anti-fascist” state of old Europe. They reject constraints dictated by historical and political context, view parliamentarianism and the “traditional” decision-making model with skepticism, and favor a “strong hand.” This audience is ready to lift the taboo on the far right, whose main voice and political representative is the AfD.

This electoral segment has long been heterogeneous: it includes diverse age, socio-economic, and regional groups. Support for such a course is no longer confined to the country’s east; it has become a nationwide phenomenon. Polls ahead of the “big election year” of 2026—campaigns in eight Länder simultaneously—already suggest the possibility of three-party parliaments, such as AfD, the Left, and the CDU, where forming a coalition without the Alternative, or even a minority government, would be mathematically impossible.

But there is another Germany. It firmly defends the parliamentary-democratic model that made the Federal Republic attractive to the world, pickets far-right party congresses, and takes to the streets in mass protests. In this configuration, Merz—like the entire broad coalition—is unable to take radical decisions: the challenges facing the country are far more complex than cutting red tape or striking a good bargain with Trump.